By Joseph D. Bryant | jbryant@al.com

Birdie Mae Davis’ name is synonymous with a decades-long legal fight to desegregate one of Alabama’s largest public school systems.

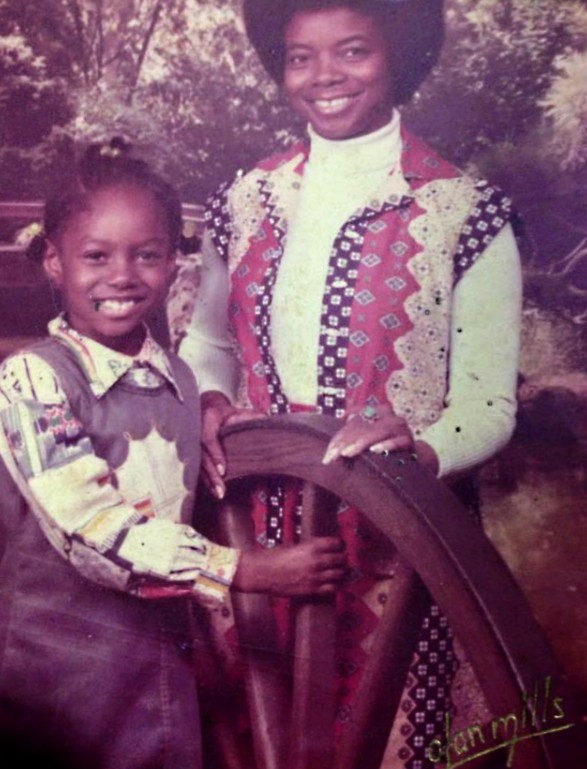

Davis, later known as Birdie D. Manning, died Sunday at her home in Birmingham following an extended illness. She was 77.

Davis was among one of the first Black students to integrate Murphy High School in Mobile in 1963.

She was just 17 that year when her parents filed a lawsuit to desegregate Mobile County schools. She, her sister Bettie, and Rosetta Gamble eventually became the first three Black students at Murphy High School.

The Davis case began when a group of Black parents filed a lawsuit that claimed the Mobile County school board violated the U.S. Constitution by failing to desegregate schools.

Previous attempts had also been made to integrate the school by Dorothy Bridget Davis and Henry Hobdy.

In spite of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954 that ruled school segregation was unconstitutional, a slew of local schools around the country remained largely segregated as communities either resisted the order or moved slowly to avoid full compliance.

In Mobile, there was no welcome sign for Davis as she entered the city’s oldest and most prestigious public school.

Instead, Davis and the other students faced hostile students and parents who taunted and threatened them. Davis and the other two students who integrated Murphy had to have daily security.

“At first, it was pretty hard because the students were very bad,‘’ Davis said during a hearing in 1965, where she described her experience at the school. “They, I would say, hated us at first. But then they started to get a little better and they started to recognize us.‘’

Davis graduated from Murphy in 1965 and went on to attend the University of Alabama, just two years after the state’s flagship college was integrated following a dramatic standoff similar to the one she faced in high school.

Davis was forever associated with the case because her name was listed first among plaintiffs in alphabetical order.

Yet, Davis for decades demurred at her role in civil rights history and instead chose a quiet life in Birmingham.

“My mother was very humble about her role in changing Alabama history, often deferring to the group of students who integrated Murphy with her as the ‘village’ – and that all of them changed the education for Black students in Mobile,” said her daughter, Faye Oates.

In Birmingham Davis worked in senior management for South Central Bell, which later became Bell South and finally, AT&T. She retired in 2002.

“She always said it was not about her,” Oates said. “Her name became synonymous with the case but her greatest accomplishment was the life she made as a mother and grandmother.”

While the Brown ruling was a legal death knell to segregation, the Supreme Court provided no instructions for enforcing the order.

The Davis case was among a series of federal cases around the country challenging segregated schools after the Brown ruling, explained Brian Duke, a social studies department chair at Davidson High School in Mobile.

“These families would be the ones that challenged racial segregation and sought equal access for their children,” said Duke, who wrote his master’s thesis on the Davis case.

“Ms. Davis’s name became synonymous with the lawsuit in the federal district court and the struggle for equal educational rights in Mobile, AL. Over 34 years, the federal lawsuit took on a life of its own as the state’s largest district worked to dismantle segregation and achieve unitary status. Its resolution had lasting impacts across Mobile County.”

By 1970, the case made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where Mobile was ordered to further expedite integration efforts.

In 1997, the case was finally dismissed by the courts, citing that Mobile had adequately integrated its public schools — 34 years after it was filed.