By John Archibald | jarchibald@al.com

Editor’s Note: In 2025, AL.com’s “Beyond the Violence” project, in partnership with The Birmingham Times, examines whether Birmingham can grow beyond its crime problem and become safer, healthier and happier.

This is an opinion column

If I know anything it is this: Birmingham is a dangerous place.

Dangerous. Like love.

So beautiful. So mysterious. So full of possibility.

I get butterflies sometimes when I come home from a long trip and see that skyline. I stare at pictures of the Cahaba River as if at a loved one. I smile just thinking of Oak Mountain or Ruffner or that little jazz club that used to be downtown, but is no more.

So fickle. So hurtful. So damn heartbreaking.

Birmingham will lift you up and knock you down, over and over again.

The first time I felt that was 1973. NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle pondered expansion, and he named nine cities with a shot at the big leagues: Seattle, Portland, Phoenix, Honolulu, Mexico City, Tampa, Jacksonville, Orlando and Birmingham.

I was too young to know much. I was 10, the same age at the time as those black and white pictures of dogs and firehoses the city’s leaders still didn’t want to talk about.

I, like the people who ran this town, just wanted to talk about football.

Businessmen Harold Blach Jr. and Frank Thomas Jr. really thought they could land an NFL franchise. They’d reserved possible names – the Alabama Vulcans and the Birmingham Vulcans – and by the next year Blach said the list had narrowed to Seattle, Tampa, Phoenix and Birmingham.

It seemed real. It seemed possible. Birmingham was the 48th largest city in America then, bigger than Tampa and more football crazy than Seattle or Phoenix.

Blach and Thomas went to the Birmingham Park Board and asked for exclusive rights to Legion Field to help secure a franchise. The board refused, and later gave exclusive rights to the upstart World Football League.

“That killed any hopes we had with the NFL,” Thomas told The News’ Jimmy Bryan back then. “We had asked the Park Board to hold off on exclusivity until after the NFL meetings. They did rescind the exclusive part, but it was too late.”

The WFL was a fun league, but it failed in two years. The Tampa Bay Bucs and Seattle Seahawks joined the NFL in 1976, and I’ll never forgive them.

It’ll break your heart, this town, and your spirit. If you love it.

At least Birmingham in those days saw itself as a big league city, a contender. More importantly, perhaps, it saw itself as a metro worth fighting for, a place that demanded political and business leaders who rallied around civic pride and recognized, if only with lip service, that a rising tide buoys us all, even when a rolling Tide cannot.

It seems like I spent my life being lifted by hopes for this town, only to see them wrecked on the shoals of our own confounding inability to get along.

But this is about now. Things seem different today. Urgent, somehow. Existential, even. If this city, if this metro is to survive, much less prosper, it simply can’t continue to divide itself. It can’t continue to make the try-hard-give-up mistakes of the past.

Two-Minute History

Let me give you the two-minute history, if only to work toward that goal. Take a deep breath, and bear with me if some of it sounds familiar.

In 1950 Atlanta was the 33rd largest city in America, and Birmingham was 34th, only 5,000 people behind. But the Klan kept setting off bombs in Birmingham, and police hadn’t caught any of the hooded scoundrels, nor tried that hard. Atlanta called itself the “city too busy to hate.” Birmingham was branded Bombingham.

By 1960 Birmingham was the 36th largest city and Atlanta up to 24th. We were still bombing. And arresting no one. And wondering why we got no respect.

In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, Birmingham hatched a couple of plans to merge the city and suburbs into “one great city,” and they failed by the slimmest margins. Mostly because white leaders in places like Fairfield and Tarrant feared Black people might gain political power. According to legend one of those votes was killed by the hands of a legislator from Mountain Brook, who feared unification would lead to the end – say it ain’t so, Jeeves – of rear-of-house garbage collection in Alabama’s toniest suburb.

In 1970 Birmingham was the 48th largest city in America, passed by the likes of St. Paul and Norfolk.

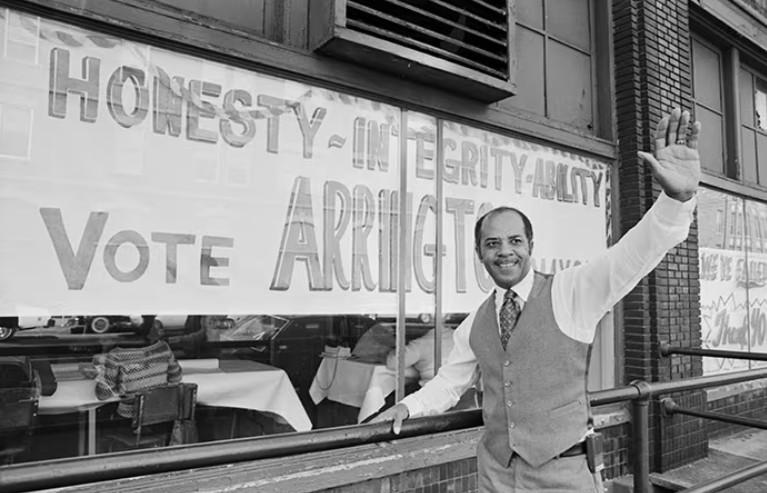

Court-ordered school desegregation prompted suburbs like Vestavia Hills to form breakaway school systems (theirs with a Rebel mascot). The NFL deal failed. The steel industry died. Birmingham elected its first Black mayor, Richard Arrington in ‘79, and that turned on the spigot of white flight.

By 1980 Birmingham was 50th in population, passed by Charlotte, which we used to think of like Jackson or Baton Rouge or Opelika.

More cities incorporated, more school systems formed, notably Hoover. The trickle of flight turned into a gusher, and by 1990 Birmingham was the 60th largest city in America.

In the ‘90s groups sprang up to call for change, for regional cooperation, for a return to civic pride. A task force called UNITY was led by former Southern Research Institute chief John Rouse, and was based on the notion that divided we fall a lot harder. It wasn’t fair, he said, that Birmingham was but 41% of the metro population but paid for most of its cultural assets. Together we could do more. It even floated another shot at a one-great-city style plan. But that idea was dead.

Nobody in the city or the suburbs wanted to risk their bits of power. Better to control a little than share in a lot.

Birmingham City, if you are curious, now makes up 17% of the metro.

In 1998, a long, expensive campaign called MAPS sought to build a dome and entertainment district, pay for mass transit, school construction and more, and pay for it with a one-cent sales tax. Birmingham proper supported it, but it was defeated in a countywide vote, largely because voters in mostly white suburbs said “Oh heck no” (eight of 10 in the northern suburbs).

In the time since, sales tax increased two cents to pay for far less ambitious things, and that pesky regional chasm grew wider. That’s my two cents.

Ups And Downs

By the year 2000, Birmingham was the 72nd largest city in America, trailing Bakersfield and Stockton and Anchorage.

There were ups and downs in that decade. Railroad Park was put into motion, along with other green spaces. Some communities began to cooperate. Birmingham’s food scene flourished, but much of its banking industry slipped away, leaving the University of Alabama at Birmingham as the dominant business in town.

Sen. Richard Shelby secured $87 million for mass transit, including light rail for the Birmingham area. He promised much, much more. If only the city and suburbs could come up with a 20% match: $17 million. They could not. They would not.

Sen. Richard Shelby secured $87 million for mass transit, including light rail for the Birmingham area. He promised much, much more. If only the city and suburbs could come up with a 20% match: $17 million. They could not. They would not.

Gov. Bob Riley was fed up with the bickering when he tried to push a bond issue to help the region. Get over it, he said. Move on.

“You need to look at it like a new start,” he said. “You need a rebirth of enthusiasm.‘’

But he didn’t get through to us.

Birmingham became a spectator sport. A bipartisan wash of corruption sent more than 30 politicians and their cronies to jail. Jefferson County filed what was then the largest municipal bankruptcy in the history of the world, the most publicity this place had gotten since Bombingham.

And by 2010 it was the 98th largest city in America, behind a bunch of suburbs like Irving, Texas; Scottsdale, Arizona; and North Las Vegas.

Pollution standards limited our ability to recruit industry. The fastest growing jobs came in the form of fast food cooks.

More groups came along. The Regional Growth Alliance built a model for governments to work together. Blueprint Birmingham, by the Birmingham Business Alliance, took it further, and the Public Affairs Research Council of Alabama won a national award for a study called “Together We Can,” which I prefer to read as “Apart We Are Tied.”

It pointed out how the metro has underperformed not just in population growth but in job growth, that our fragmented structure caused us to lag behind those cities in the South that used to lag behind us, that the future promises to be just as stagnant unless we really do the thing we have only talked about all these years.

Do something. Finally this time.

That report said what anybody with the ability to look beyond their own front yard could see, now, and 50 years ago, and 50 years from now.

“The negative effects of fragmentation weigh not only on the center city but also on the metropolitan area as a whole. The fortunes of the central city and its suburbs are interlocked.”

And in 2020 Birmingham was no longer in the top 100 cities. It is now the fourth largest city in its state.

I promised a two-minute history. I hope you read fast. It’s hard to put 75 years of heartbreak into 120 seconds.

But this moment calls us all to understand what every one of those efforts has tried, and mostly failed to hammer home. We are in this together.

For good or for ill.

In A Dangerous Time

Birmingham is in trouble. In a dangerous time.

When I say dangerous, I am not just speaking of crime. When I say Birmingham I am not just speaking of the 196,644 people inside these city limits (144,000 fewer than when I was born).

I’m talking about that city and the 37 that surround it in Jefferson County. I’m talking about the 89 cities across this metro area that, admit it or not, feed on the success of the whole.

I’m saying it at a time when millions of dollars that fund medical research at UAB and Southern Research are being withheld, money that provides not just livelihoods for people across the metro area, but their very reason to be here.

I’m talking in a time (like every other time) that the Alabama Legislature wants only to punish us, when race and politics and economics and education and income segregate us. If we are to survive, let alone prosper, we must do better than those who came before.

Or your job will be gone. Or your house, in the city or the suburbs, won’t be worth what you paid for it. Or your streets won’t be as safe, or your opportunities will be more limited. Or your children will have less than you did. Or your life will not be as rich as it could be.

This is important.

We need leaders to lead. For all of us.

We need smart people to speak and act. For all of us.

And we need to respond. Each of us.

We need to believe, and love and hold on tight. Or this beautiful, painful, dangerous thing we call Birmingham will break our hearts.

John Archibald is an opinion writer, a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize and author of “Shaking the Gates of Hell: A Search for Family and Truth in the Wake of the Civil Rights Revolution.” He was awarded the 2018 Pulitzer for commentary and was lead reporter on the 2023 Pulitzer for Local Reporting.