By JOCELYN NOVECK | Associated Press

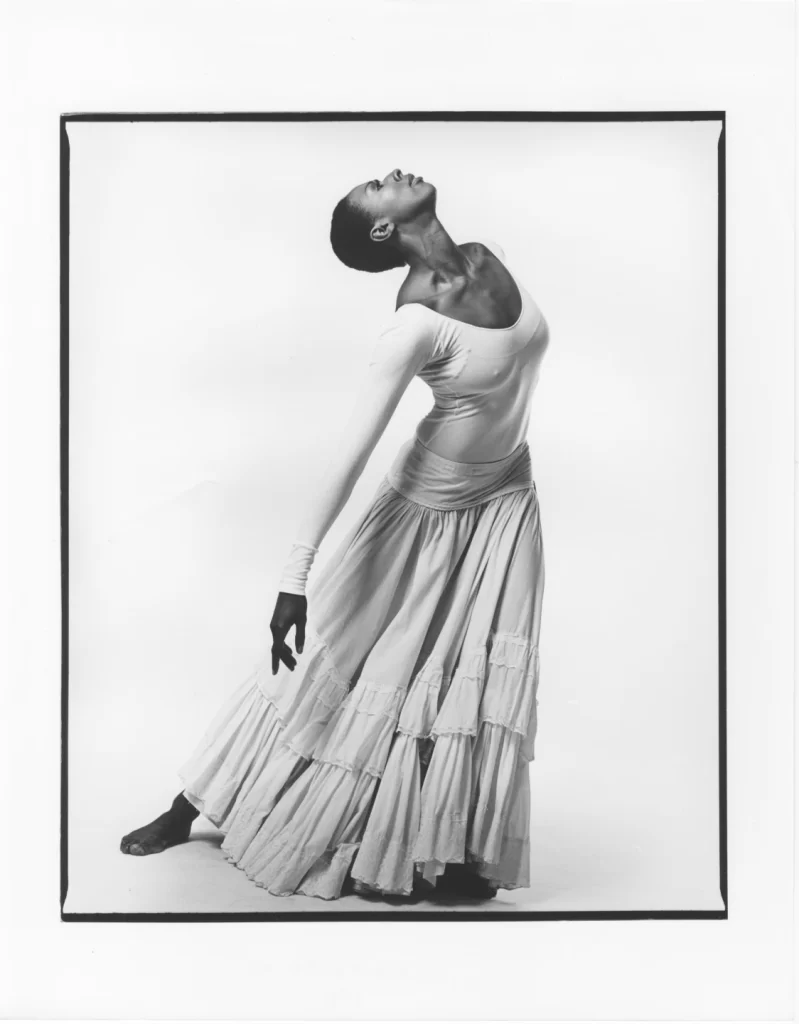

NEW YORK — There are few images more indelible in the history of American dance: Judith Jamison, regal and passionate in white leotard and long ruffled skirt, punching the air in “Cry” — Alvin Ailey’s piercing solo about Black womanhood.

That searing 1971 piece made her an international star. But it was truly only the beginning of Jamison’s decades-long career atop modern dance, onstage and off. As Ailey’s hand-picked successor beginning in 1989, she led his namesake company for more than 20 years, helping it become the most successful modern dance troupe in the nation.

“It’s amazing,” Jamison, who died Saturday at 81 after a brief illness, reflected in an interview with The Associated Press in 2018, marking the company’s then-60th anniversary. “I find it remarkable that we still exist today,” she said. “And I think Mr. Ailey would be absolutely beside-himself happy, that something he started 60 years ago could blossom into everything he imagined.”

And likely much more. Jamison brought the company not only continued global exposure and crossover cultural appeal but economic stability and growth, putting it in “a stratosphere that Ailey couldn’t even imagine,” said Wendy Perron, author and former longtime editor of Dance Magazine.

Perron attributes Jamison’s success, in a world when many dance companies struggle to survive, to her unique personality and ability to forge relationships. “There was a warmth and magnetism about her — everyone wanted to be with her,” said Perron. “There was a light shining around her.”

It was in “Revelations,” a telling of Black history through spirituals and blues, that Jamison also made a mark as a dancer, holding a white parasol with one arm as she undulated the rest of her body in a baptismal scene – “the umbrella woman,” as the part became known.

To this day, “Revelations” appears on most of the company’s programs, at home in New York and on tour, and is referred to as the most-seen work of modern dance. (It’s hard to conceive of anything comparable.) “Revelations” was even performed at the White House, at a dance event hosted by Michelle Obama in 2010, in which the first lady paid tribute to Jamison, calling her “an amazing, phenomenal, ‘fly’ woman.”

Obama also told Jamison from the stage that a photo of her in “Cry” had been “the only piece of art” in the Obamas’ home before the White House, and that her daughters, Malia and Sasha, had asked her: “Is that the lady in the picture?”

A year later, retiring as artistic director, Jamison exclaimed to a cheering crowd at New York City Center gathered to honor her: “I have come a long way from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania!” That’s where Jamison was born in 1943 and raised, her childhood spent training in various dance forms, including ballet, modern and tap.

“I knew I had so much energy back then – just too much for everybody,” she quipped in a 2023 podcast interview. “But my parents went, ‘OK, lets direct her this way.’” She credited her mother’s dedication — she made her daughter’s costumes, and “would massage my legs when I got home from class.”

In 1964, famed choreographer Agnes de Mille had seen Jamison in a class and brought her to New York to participate in a production of American Ballet Theatre. Soon after, the young dancer went to an audition for a TV special — and flubbed it, she said. But Ailey was there, and she soon was invited to join his fledgling company.

She wasn’t sure what he saw in her, she has said, other than a look: “Small head, broad shoulders, long arms and long legs.”

With the young company, Jamison traveled to Europe and Africa. Even then, it took her a few years to appreciate that this could be a career. Partly this was because, as she noted in the 2023 podcast, “We were getting paid doodly-squat” – envelopes that sometimes contained a $20 bill, and sometimes just a thank-you note.

But she soon realized that she loved dancing, traveling and being around other dancers. The Ailey troupe was also a rare outlet at the time for Black talent. “There were no outlets,” she said. “There was no place for us to say, “Hey look, this is our artistry, this is our culture, and guess what else we can do?”

Ailey chose Jamison for “Cry” in 1971, a work he dedicated to Black women everywhere, but especially mothers. On opening night, Jamison has said, she didn’t know if she was going to make it though the demanding, 16-minute solo.

She told the Hollywood Reporter that “when the curtain went down, I was on the floor.” She got up to take a bow, “and I kept taking bows over and over until I don’t know which number it was, but they were still screaming and yelling.”

Over the next two decades, Jamison often appeared as a guest artist with companies around the world, and left the Ailey troupe in 1980 to star on Broadway in “Sophisticated Ladies.” She also formed her own company, The Jamison Project.

Then an ailing Ailey told her he’d like her to run the company after him.

Jamison recalled, in the AP interview in 2018, being present as Ailey died, along with fellow dancer Sylvia Waters and Ailey’s mother.

“We were in his room as he passed, and usually you see in movies, that people have their last breath and they breathe out. But Mr. Ailey breathed IN. We expected him to breathe out, and he didn’t. So I think what we’re living on now, is his breath OUT … that air, that vision, that dream.”

Among her many laurels, Jamison was awarded Kennedy Center Honors in 1999 and a National Medal of the Arts in 2001.

Perron, the former Dance Magazine editor, said she felt Jamison had been overlooked somewhat as a choreographer. She pointed to “A Case of You” — a duet to Diana Krall’s version of the Joni Mitchell classic and part of Jamison’s 2005 “Reminiscin.’” The duet, Perron said, was “happy and sad and passionate and inventive .. you really believe these people are passionately in love.”

Jamison passed the artistic director baton to choreographer Robert Battle in 2011. Looking back, she has said one of her proudest moments at the company was the creation of the Joan Weill Center for Dance in 2005, a midtown Manhattan home for the company.

“Majestic” and “queenly” is how Waters, now Ailey II Artistic Director Emerita, described her late colleague.

“She was a unique, spectacular dancer,” Waters said. “To dance with her and to be in her sphere of energy was mesmerizing.”