By Solomon Crenshaw Jr. | Alabama NewsCenter

Birmingham’s Negro Southern League Museum saluted Napoleon Williams and Charles Harris on Sunday afternoon as unsung legends of the Birmingham Industrial League. The pair got to share the honor with dozens of other former ballplayers who worked and played for industrial companies in the Magic City.

The event was a sort of reunion for the former players and their families as they exchanged stories from their playing days. For many, their play in the Industrial League was a precursor to them becoming household names in the Negro Leagues.

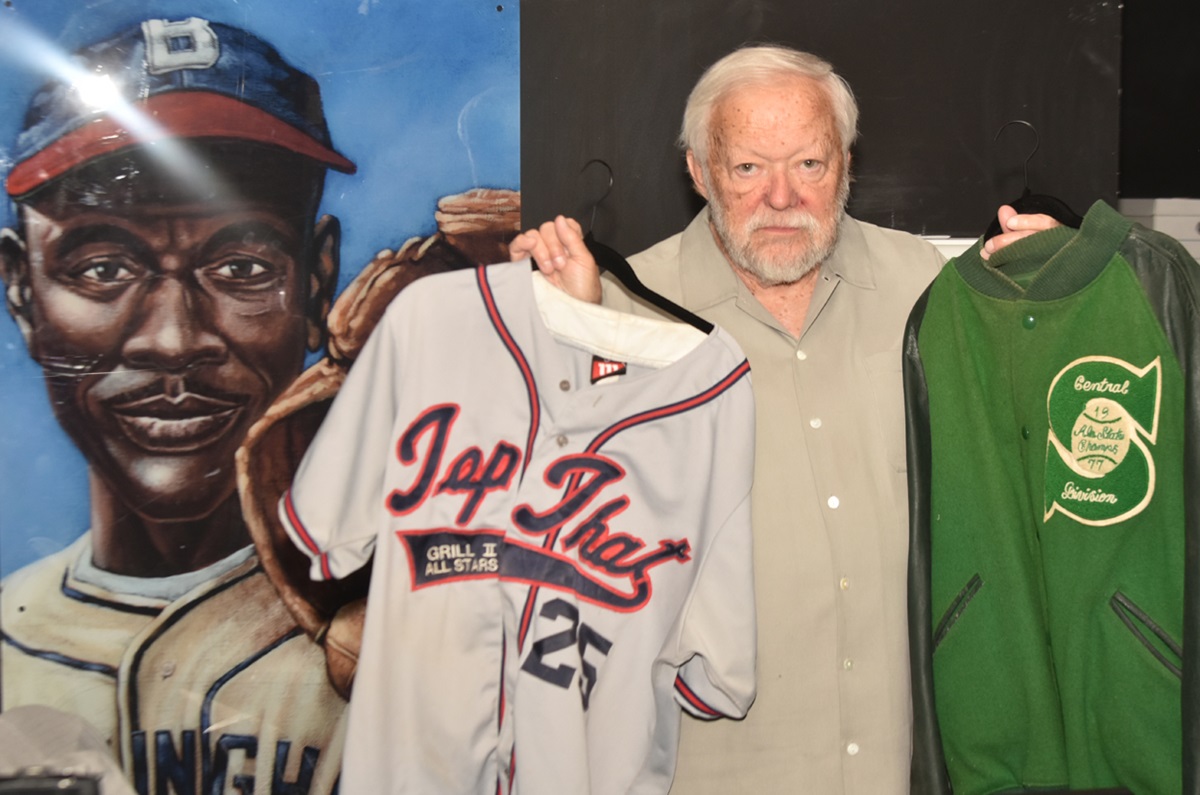

“You’ve got to realize that pretty much every Negro League player that came out of Birmingham started in the Birmingham Industrial League,” said Dr. Layton Revel, who supplied the artifacts in the museum. “And a large percentage of those players from Birmingham after their playing careers were over, played in the Industrial League, post professional.”

Generations ago, Birmingham Industrial League was a proving ground for a young ballplayer who wanted to assertively answer the question, can you really play? Did he have the skill set that would let him play at the next level?

At the other end of the spectrum were former Negro League players who came back to play with the industrial squads like American Cast Iron Pipe (ACIPCO), Stockham Valves & Fittings, the Alden Cardinals, the Edgewater Blue Sox, Sloss Furnaces and U.S. Steel. It gave those former pro players an opportunity to play competitive baseball.

“The Birmingham Industrial League is part of the fabric of Birmingham itself,” Revel said. “It was here in the early days with the first plants that started teams up, and they’re still playing today. Teams have changed. The league’s changed names, but it’s still industrial league baseball.”

Harris, who was absent Sunday, and Williams were honored because of their advanced age and the skill each displayed in his playing days. Harris played for Stockham Valve and Fitting while Williams played for Ensley Steel.

Revel described Harris as a quiet, unassuming man.

“He’s not braggadocious,” the baseball historian said. “But … for his career with Stockham, Charlie Harris had a career batting average of .346. That’s good at any level. They were both very good ballplayers. Napoleon Williams played centerfield for Ensley for 15 years.”

During the ceremony, Revel introduced Williams as a player who for at least a decade and a half covered centerfield for Ensley Steel. The honoree was quick to correct him.

“I owned centerfield,” Williams said as laughter filled the room.

“If you came out thinking you were a ballplayer, you weren’t playing centerfield,” Revel said.

“Not for Ensley,” Williams said. “Not in my time.”

Following the ceremony, Williams and Harris threw out ceremonial first pitches prior to the Birmingham Barons playing the Pensacola Blue Wahoos at neighboring Regions Field. In a skybox during the game, Williams reflected on what might have been. The 91-year-old recalled playing for a manager who took advantage of his speed on the basepaths by having him bunt to set the table for teammates to drive him home.

“Because of my speed and my ability to bunt, we were able to score a lot of runs,” Williams said. “My coach was hung up on winning ball games, not developing Major League ballplayers. There were times when I had to bunt with the bases loaded in the bottom of the ninth inning with two outs. I still had to bunt.”

The centerfielder remembered one game when a scout was on hand and he was told to swing away. He struck out four times. But the scouts missed seeing Williams’ ownership of centerfield when the Stockham shortstop sent a ball deep to centerfield with the bases loaded and two outs.

“When the ball left the bat, I started running toward the centerfield fence,” Williams recounted. “Just before I got to the fence with my hands up over my head and running away from home plate, the ball fell in my glove. I do believe that if those scouts had been there that night, they’d have signed me.”

Revel said he hopes to keep the memory of the Birmingham Industrial League alive.

“What we’re trying to do is to preserve the history of these different teams and the artifacts and the legacy,” he said. “I met last (Saturday) night with a gentleman that his father had played, Oscar Butler Williams. He had a bunch of his father’s stuff and we’re going to create an exhibit at City Hall on it.”