By Ryan Michaels

The Birmingham Times

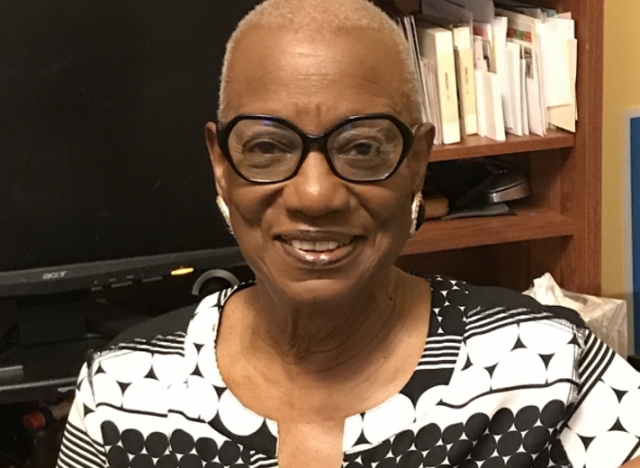

When Marva Douglas began her tutoring business in Fairfield, Alabama, and searched for teachers, she learned a lesson of her own from one retired instructor who had sold her car. The retiree told Douglas not to rely on public transportation.

Douglas decided to see for herself.

She went to the stop nearest her tutoring center: the J.C. Penney at the former Western Hills Mall. Another woman stood at the bus stop waiting to get to what was then Cooper Green Mercy Hospital, Jefferson County’s medical facility for indigent patients. The rider was in pain, Douglas recalled.

“We were waiting there, and we waited, and we waited. … The five o’clock bus was supposed to come, and then, at that time, people were just piling up … waiting,” Douglas said.

Even after getting on the bus, the woman would have to ride all the way down to Central Station in downtown Birmingham and then wait for another bus to get to Cooper Green in the Southside community. Getting back was just as hard, Douglas remembered.

That experience in the 1990s led to Douglas telling everyone she encountered about the need for improved public transit in the Birmingham area—and she has been a transit advocate ever since.

In the early 2000s, Douglas began attending meetings of the Birmingham-Jefferson County Transit Authority (BJCTA) board. During the public comment portions of the board meetings, Douglas would share her thoughts about Birmingham’s transit.

Around 2004, she was appointed by Birmingham City Council to the former Transit Advisory Committee (TAC) for the BJCTA. She’s also been a member of the Citizens United for Regional Transit (CURT) and the Transit Citizens Advisory Board (TCAB), the official group responsible for sharing the concerns of Birmingham area transit riders with BJCTA board members.

Douglas pointed out that organizations like the BJCTA are significantly underfunded. To get that money, she said, the state of Alabama should be helping out. In 2018, the Alabama Legislature passed a bill creating a Public Transportation Trust Fund, but no money has gone into the account.

The Activist

Douglas grew up in Charleston, South Carolina, raised by her grandparents Elizabeth White and Robert Benjamin Lucas. Douglas’ mother died when she was a toddler, and her father lived with his new family on the other side of Charleston.

Douglas was a member of Charleston’s Emanuel African Episcopal Methodist Church, often called Mother Emmanuel, where white supremacist Dylan Roof killed nine members of the church in 2015. The “rampant, raging hate” of Roof “devastated” her, Douglas said. “That church gave me a life,” she added. “It nurtured my talent. I sang. I learned to write poetry. There’s just so much of me that was in that building he tried to destroy people in, … and, in a way, he destroyed me,” she said.

Looking back on her life in Charleston, Douglas talked about graduating from Burke Industrial School in the city in 1957. She then went to Greensboro, North Carolina, where she attended Bennett College and helped to integrate lunch counters in North Carolina.

“We marched, and we sat in Woolworths [part of a chain of general retail merchandise stores]. I was one of the ones that didn’t get arrested, but I did get on television because they always had this huge poster of a Black hand and a white hand connecting. Whoever was carrying that poster always wound up on TV,” recalled Douglas, who said she carried the poster.

After graduating from Bennett with a degree in early childhood education in 1961, Douglas moved to Waynesboro, Virginia, where she taught second grade at the Rosenwald School, which closed in the mid-1960s. Rosenwald Schools were part of “a community-based movement [that] shaped the educational and economic future of an entire generation of African American families and exclusively served more than 700,000 Black children over four decades,” according to Smithsonian Magazine.

Douglas then moved to New York City, where she taught for about 10 years. In 1972, she moved to Birmingham when her husband, Sylvester, was transferred to the city through his job with IBM.

“I moved here, I was pregnant, I was unhappy, and I divorced him,” she said.

Fortunately, Douglas had saved some money and could get her own apartment as she began the search for a new job. One of her first stops was the South Central Bell Telephone Company (SCBTC), later called BellSouth Telecommunications, until it was acquired by AT&T in the mid-2000s.

Dream House

She also began to look for a dream house that would be stairs-free. In 1977, Douglas found the house—a one-level in Midfield, to Birmingham’s Southwest. She moved in January 1978, and that’s when “the terror began,” she recalled.

Rocks were tossed through her window, and Douglas installed new windows that were much more resistant to breaking. Then, one Friday in April, around 2 a.m., Douglas was awakened by a large “swooshing” sound.

“I sat up in the bed and realized, ‘Well, it’s not in the house with me,’” Douglas said.

Someone had set fire to a cross in her yard, a practice commonly used in the South to intimidate Black people, often performed by members of the Ku Klux Klan, a white supremacist terror group dating back to the abolishment of slavery in 1865.

Douglas called the police, who were always responsive to her calls. They wanted to remove the cross, and Douglas said, “No.”

She recalled telling the officers, “‘I’m a good neighbor. If my neighbors want me to have a cross in my yard. I will have a cross in my yard.’ That’s how foolish I was.”

A First in the South

Meanwhile, at the phone company, Douglas was hired in the public relations department and promoted to a management position. Later, she learned she was the only Black person in management not only for the phone company in Birmingham but anywhere in the five-state region the company served, which included Alabama, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee. She retired in 1991.

Today, the transit activist still takes the bus in Birmingham.

“I like being on time when I have meetings or am meeting someone for lunch or … something like that,” Douglas said.

She used to regularly walk the mile from her home to the Western Hills Mall stop to take the bus into downtown Birmingham, but the trek has become significantly more dangerous since the road was paved about three years ago, so Douglas stopped.

“That was good for my health,” she said. “Sometimes, I used to even walk from my home to Fairfield, to the bank [because] walking is good exercise. … If people are forced to do it, which many have to do now, [and] can’t get a bus that takes them [where] they need to go on a regular basis, that’s really sad,” Douglas said.

This story originally appeared in the Birmingham Times on June 7, 2023.