By Michael Sznajderman

Alabama News Center

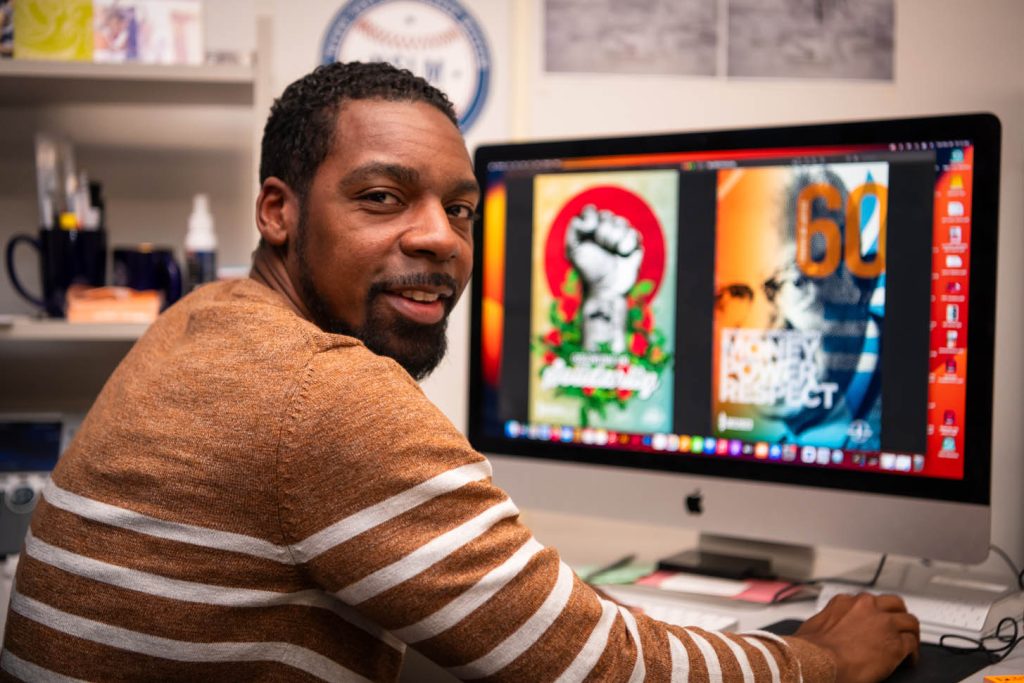

In a modest, windowless office in the basement of Birmingham City Hall, a pair of graphic designers are charting an artistic course through one of the most important years in the city’s history. And their work is getting noticed.

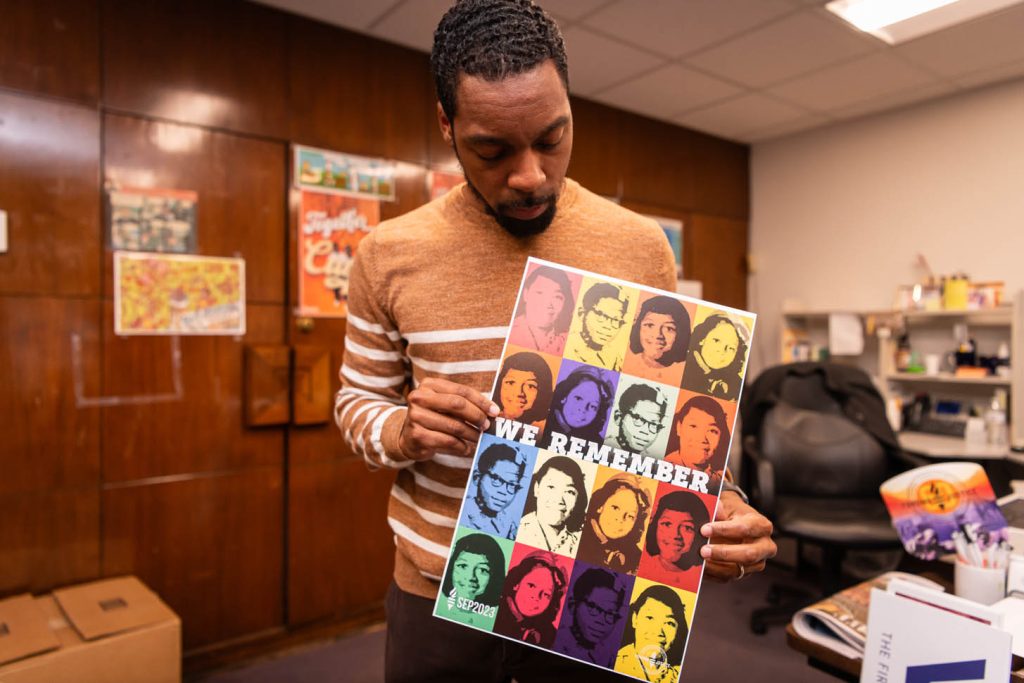

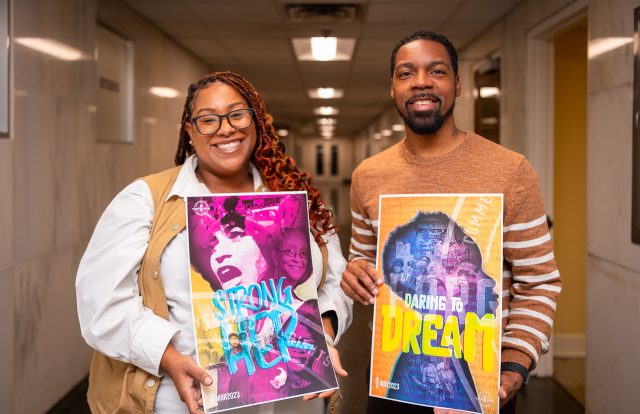

Marcus Watts, 41, and Bre Rudolph, 36, the city’s graphic design team, are putting the finishing touches on the last in a series of commemorative posters that reflect on the 60th anniversary of the climactic human rights campaign that took place in Birmingham in 1963 – a movement that resulted in the dismantling of the city’s Jim Crow segregation ordinances and federal civil rights legislation that stuck a dagger in racial separation laws nationwide.

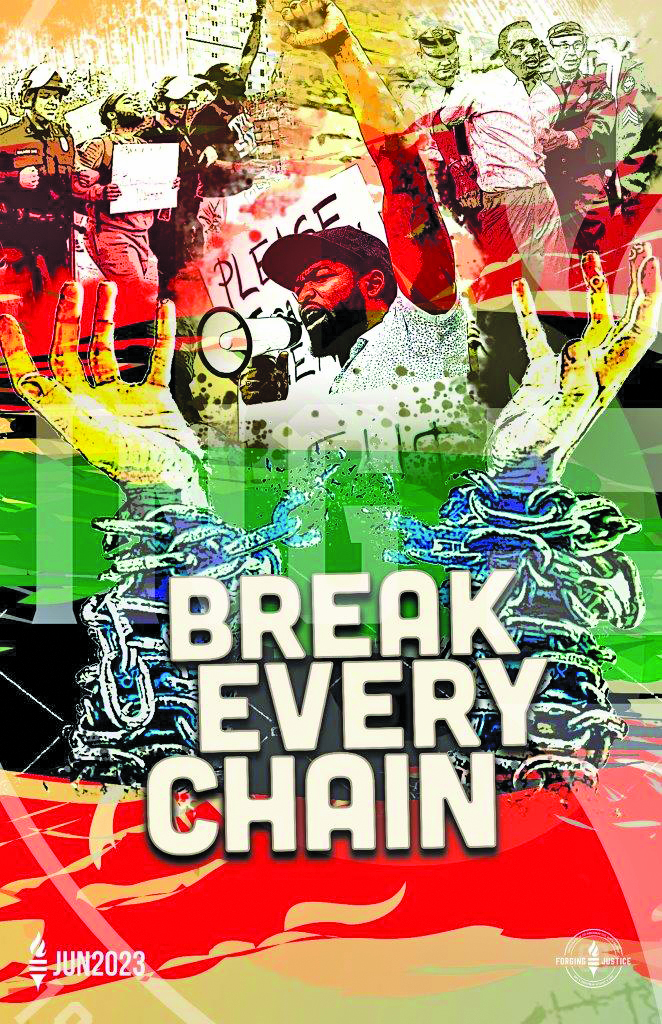

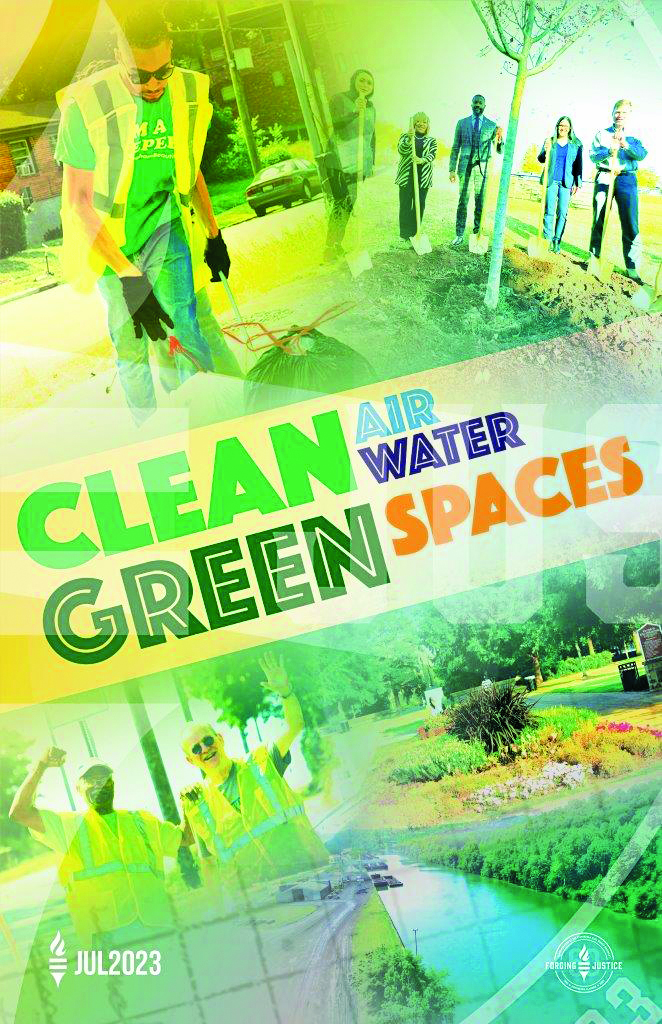

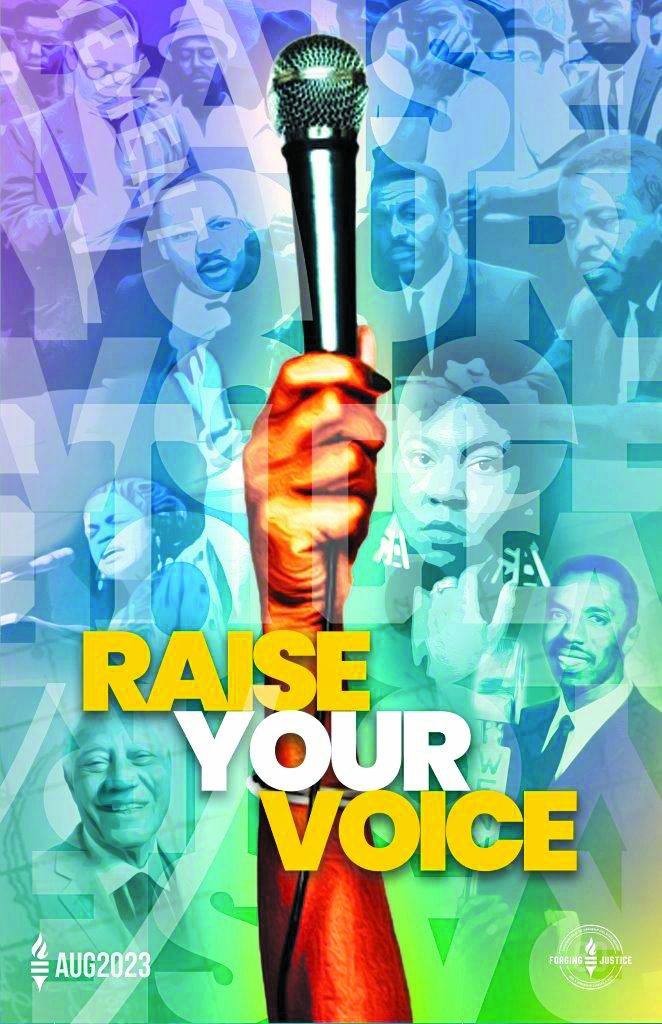

Every month this year, the city has issued a new poster tied to the 1963 anniversary – each one promoting a different theme that peers back to those days, but also looks forward. Each poster vibrates with evocative scenes set amid a rainbow of bright colors and flowing fonts, provoking powerful emotions.

Indeed, as people all around town learn about the posters, more and more of them are flocking to City Hall to grab the latest one before it’s gone – which has prompted the city to reprint some months to meet the burgeoning demand.

“We’ve just been grinding,” Watts admitted with an outtake of breath. “But it’s good to know it’s getting out there,” referring to the buzz surrounding the posters. He acknowledges the project has been one of the most gratifying of his career.

Rudolph added: “I tell Marcus a lot – graphic designers don’t always get a lot of praise or visibility.”

She said the posters “show who we are creatively, and how proud we are of where we live.” She and Watts are both Birmingham natives and products of Birmingham public schools.

From 1 Poster To 12

The poster project didn’t begin so ambitiously, Watts and Rudolph said. When they first met with city staff about a year ago, the intention was to create one poster and a single theme to promote the 60th anniversary.

But looking back on 1963 and the multitude of significant events that took place throughout the year related to human rights, it became clear that a single poster wouldn’t cut it.

Among the momentous events that year in Birmingham:

An economic boycott of segregated department stores in the first months of the campaign.

The arrest of civil rights leaders including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in April, and King’s devastating answer to movement critics in his now-famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

The city’s shocking use of police dogs and high-powered firehoses to attack defenseless child protestors in May, and …

The horrific terror-bombing of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in September that killed four little girls, plus the racial murder of two Black boys that same day.

Plus, there was the months-long legal and political crisis that year around the refusal of virulent segregationist and Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor to relinquish power, even though he had been voted out of office and a new mayor-council voted in. Ironically, Rudolph and Watts, who are both Black, work in the same building where Connor once ruled with an iron fist.

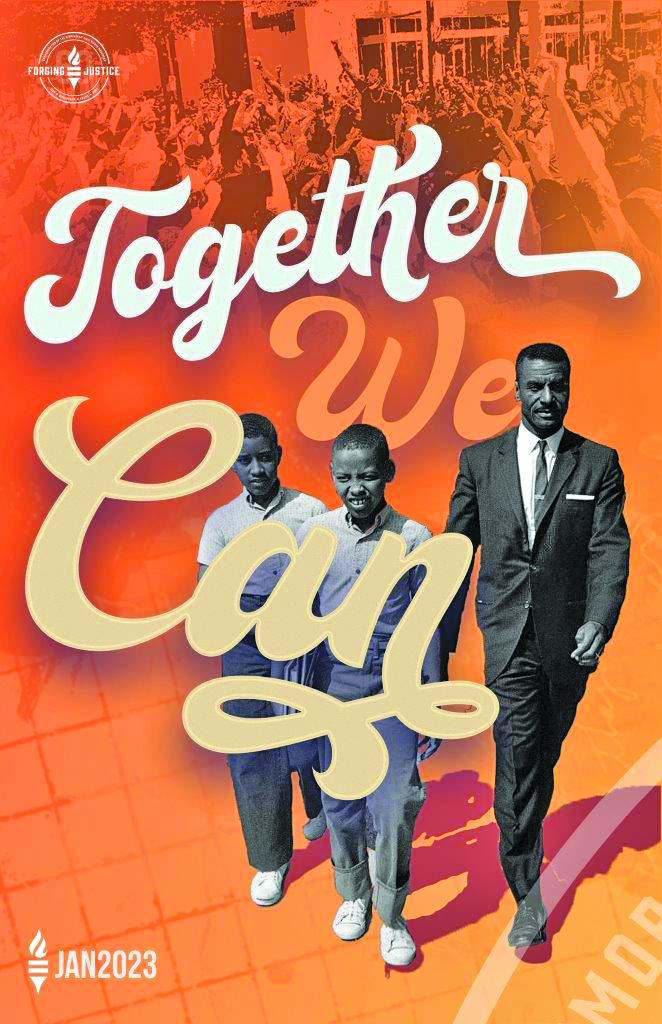

It was Rudolph who tackled January’s poster, which features the unifying theme, “Together We Can.” It is anchored by a historic image of a young Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, Birmingham’s trailblazing civil rights activist who persuaded King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to come to the city to take on the Bull and mount a coordinated campaign to topple legal segregation. Standing aside Shuttlesworth in the poster are two Black boys, symbolizing the children who not only played such an important role in the 1963 campaign, but a younger generation who will be responsible for taking on the challenges of the future.

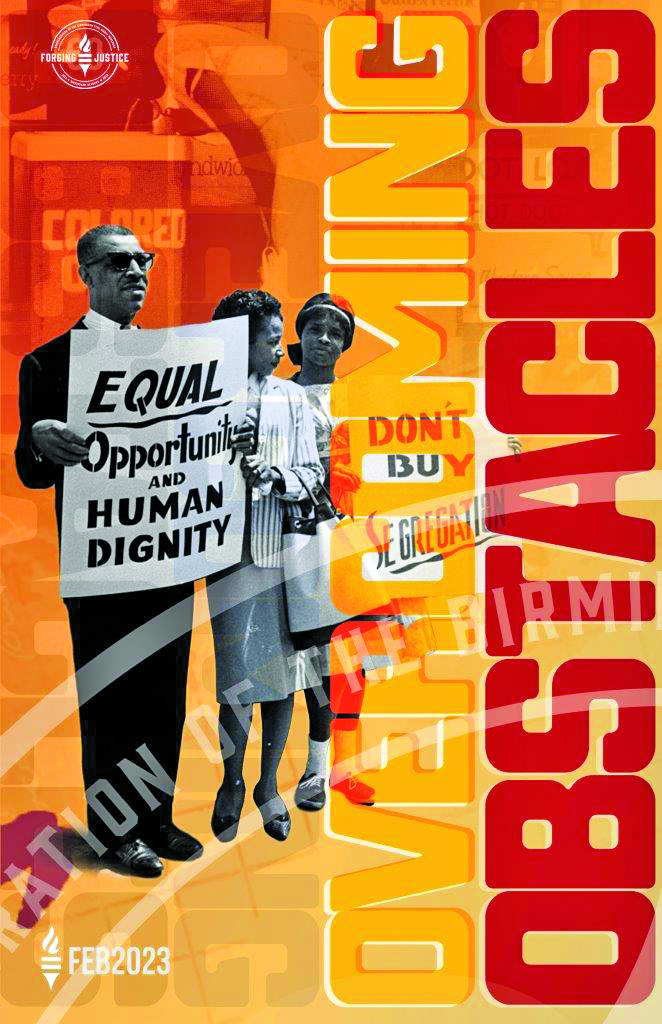

In February, the theme was “Overcoming Obstacles.” That poster shows Blacks demonstrating against the city’s segregated retail stores during the “selective buying” portion of the campaign. Watts took the lead on this poster and subsequent ones, with Rudolph taking responsibility for designing the backgrounds for all the remaining posters, as well as taking on the historical research.

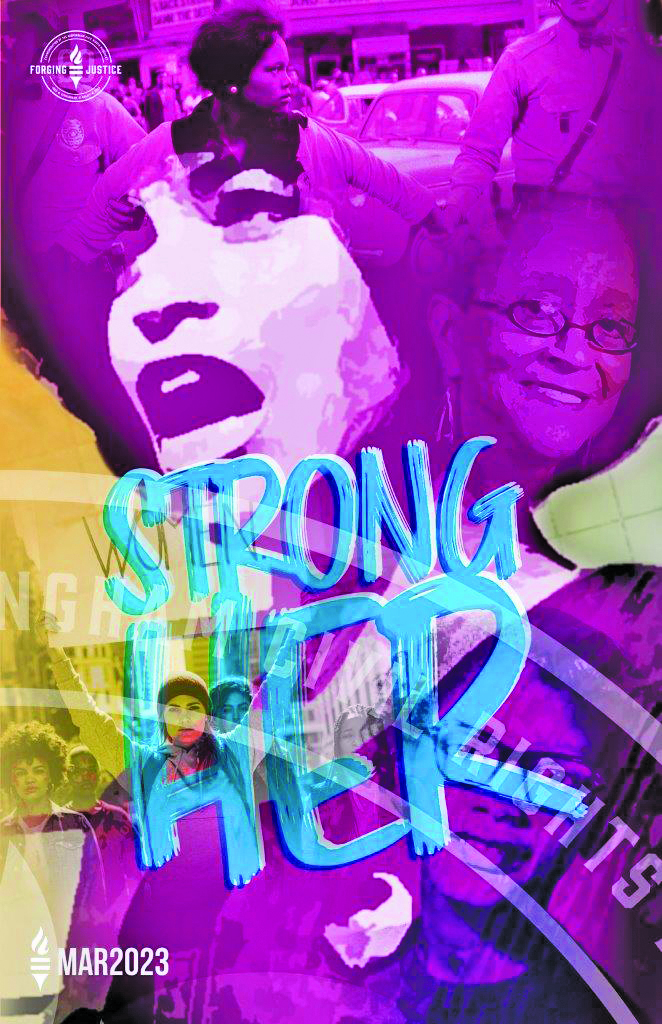

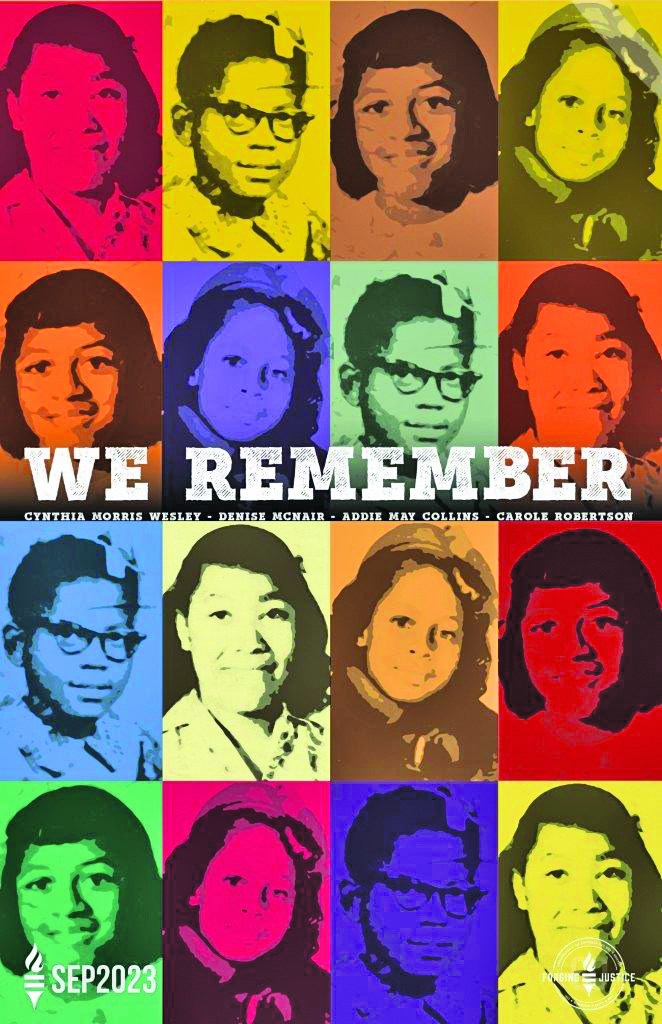

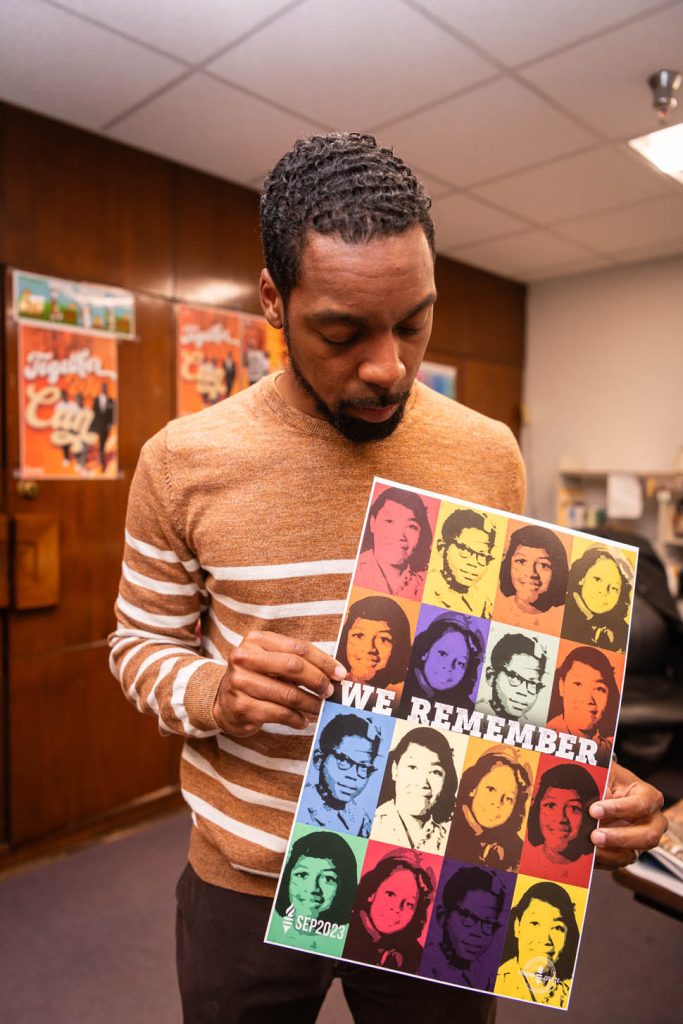

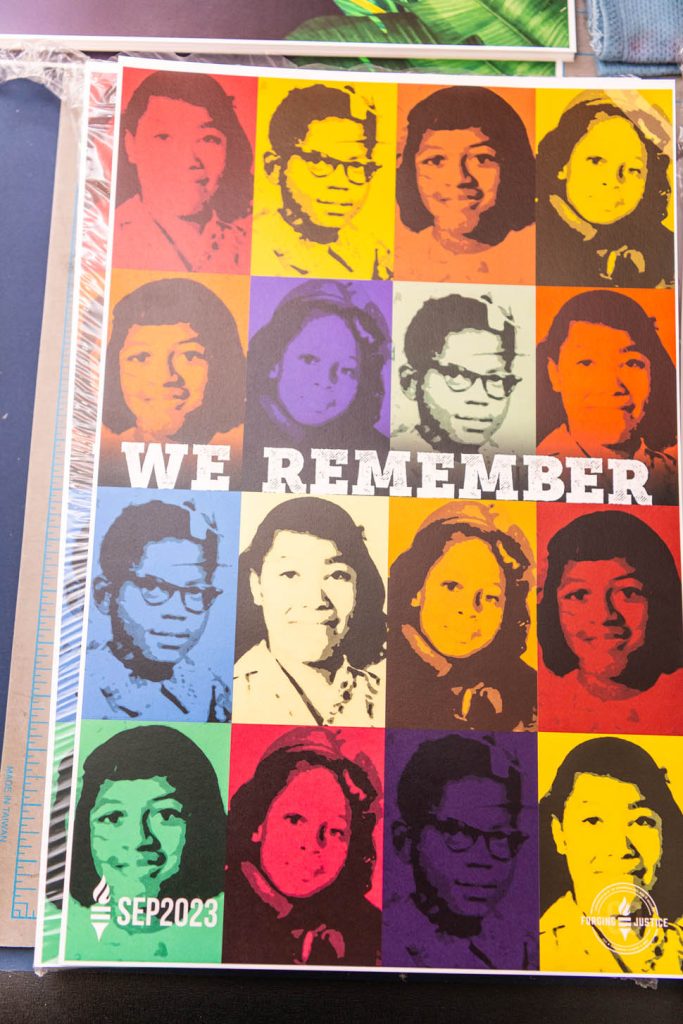

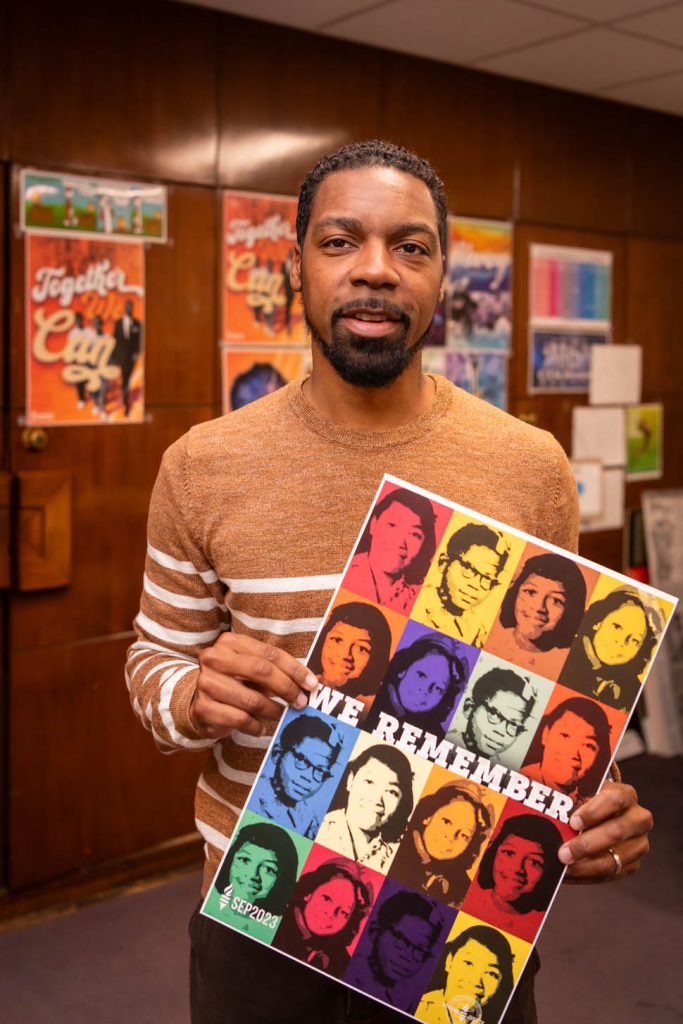

Local personalities figure prominently in many of the posters. In March, Women’s History Month, it’s activist and academic Angela Davis as the central image, supporting the theme, “Strong Her.” In September, the month of the Sixteenth Street bombing, the theme is “We Remember.” That poster floats multiple black-and-white portraits of the four murdered girls over rectangular blocks of glowing green and deep crimson, purple and burnt orange, in a style reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s pop-art prints.

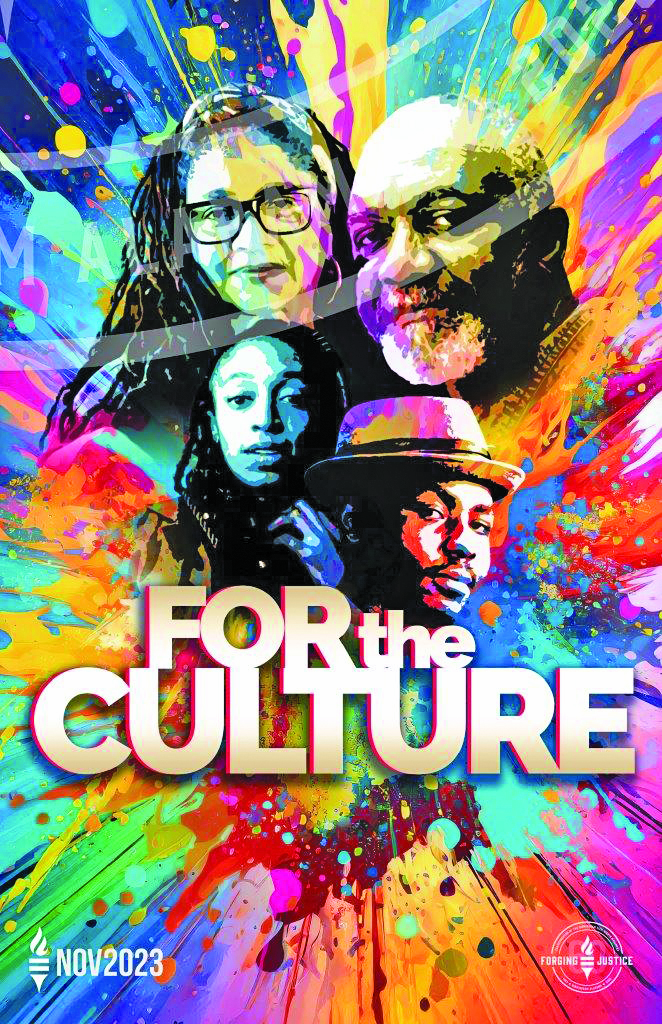

Other locally famous folks in some of the posters include Jesse Lewis, founder of The Birmingham Times newspaper that focuses on the city’s Black community; Shelley “The Playboy” Stewart, the radio DJ who sent coded messages to the child protestors and who later became a prominent business leader in the city; and Ashley M. Jones, the youngest and first person of color to be named Alabama’s poet laureate.

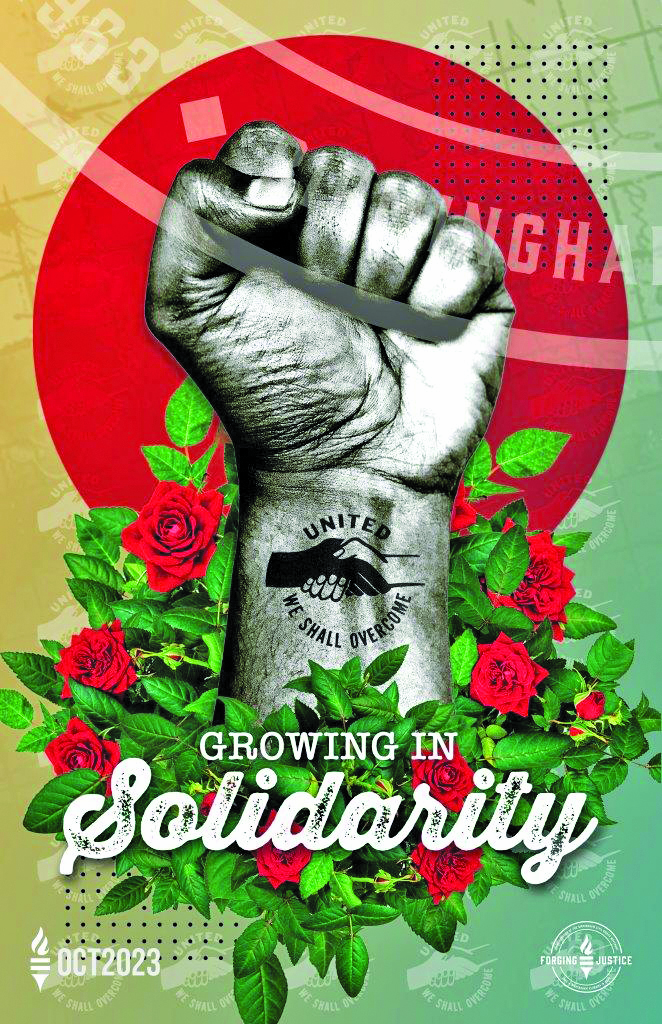

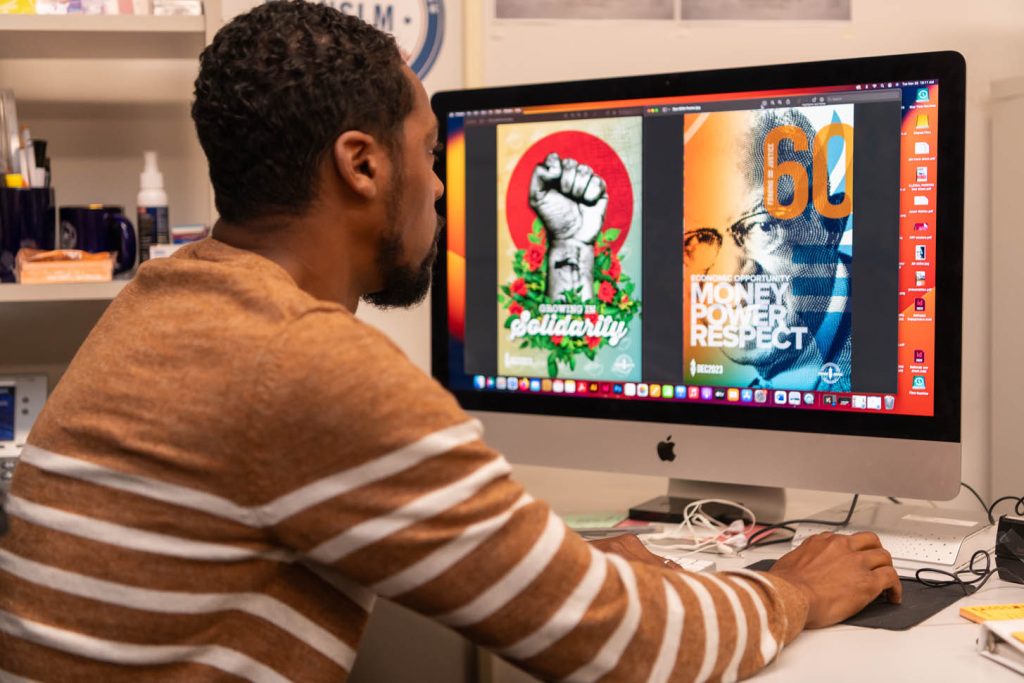

One of the most striking posters is October, with the theme “Growing in Solidarity.” It features a clenched Black fist in grainy black and white, surrounded by a wreath of luscious red roses. The poster reprises a symbol used on campaign buttons during the 1963 protests: a black hand and a white hand firmly embracing, with the words “United: We Shall Overcome.”

Watts said the poster was meant to honor the ongoing, worldwide human rights movement and its dynamic growth – symbolized by the lush, vibrant blossoms in the scene. But Watts also noted that roses can have thorns, and that protest movements – like the one etched in Birmingham’s history – “can get rough at times.”

‘Life Of Its Own’

While Watts and Rudolph toiled over the design of the posters, which are being reproduced across the hall in the city’s print shop, they also had to stay on top of all the other design and graphic requests coming to them from all of the city’s offices and departments. Requests can range from simple page layouts, to logos, to vinyl banners, including the ones that stretch across Rev. Abraham Woods Boulevard downtown that promote major upcoming events in town. Their creative work can also be viewed inside and in front of multiple city offices and institutions, from the bold graphics greeting visitors at the Negro Southern League Museum to giant images of football players on the walls outside the headquarters of the Birmingham Park and Recreation Department at historic Legion Field.

Watts and Rudolph often must adjust their designs to align with the preferences of city leaders and supervisors. But in the case of the 1963 poster series, they were given extraordinary creative license. The result: works of art that will clearly endure beyond the events that marked this anniversary year.

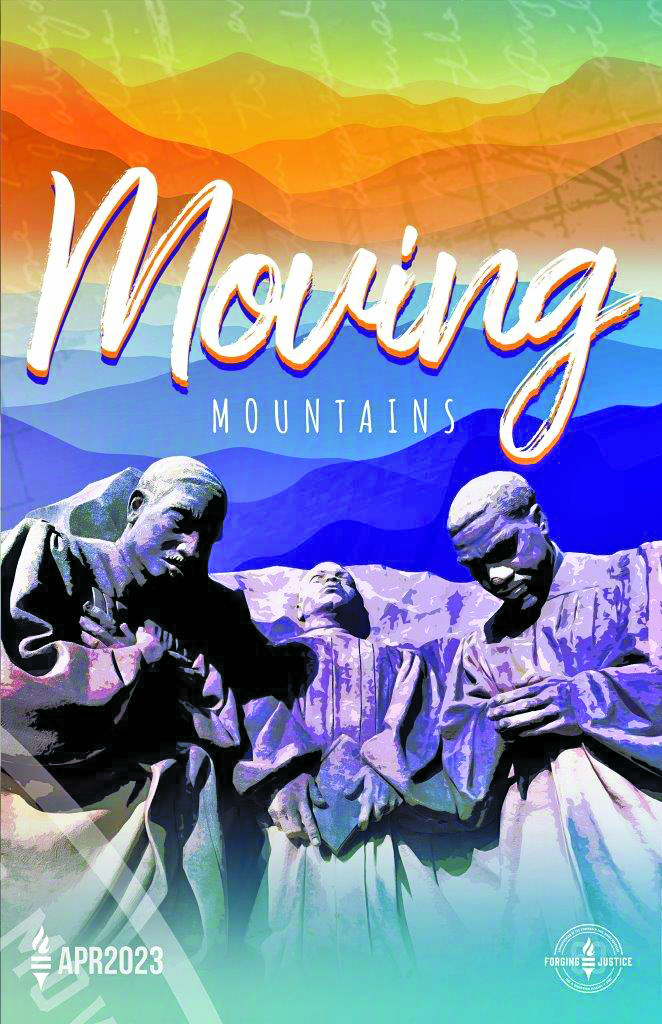

There’s another, clever element found in the posters that make them even more memorable. Not only does each poster stand alone, artistically; they also fit together, intentionally.

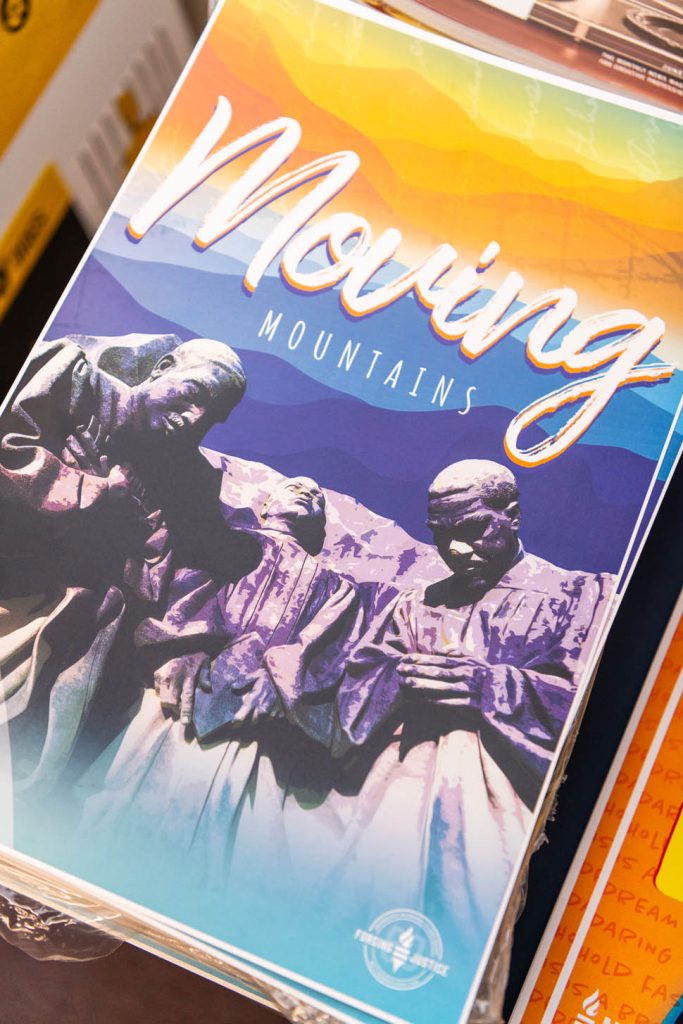

Stacked four across and three rows high, the 12 posters create a giant tableau of places, faces and events that made 1963 so important to Birmingham. What’s more, when the posters are placed that way, a subtle underlying image emerges that touches all the posters, binding them together; it’s the official “Forging Justice” logo, designed by Watts and Rudolph, that is being used throughout the city to commemorate the 60th anniversary.

“We wanted all the posters to look different, but also to come together,” Rudolph said. “We wanted each poster to hark back to something from the past, but also find parallels to now.

“It really took on a life of its own,” Rudolph said of the poster project.

“It’s Still Kind of Surreal”

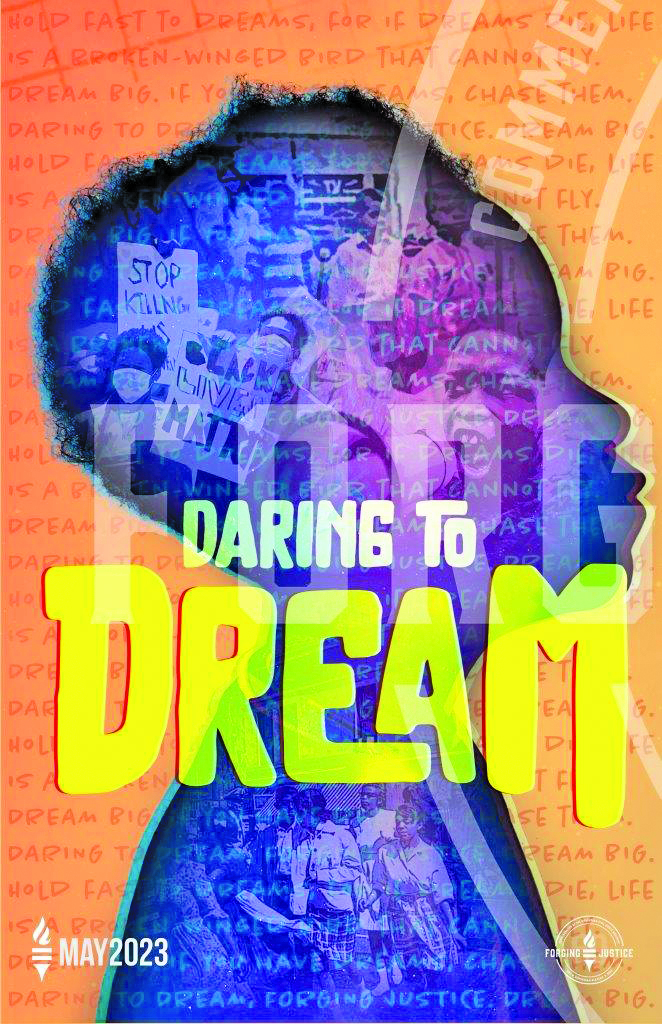

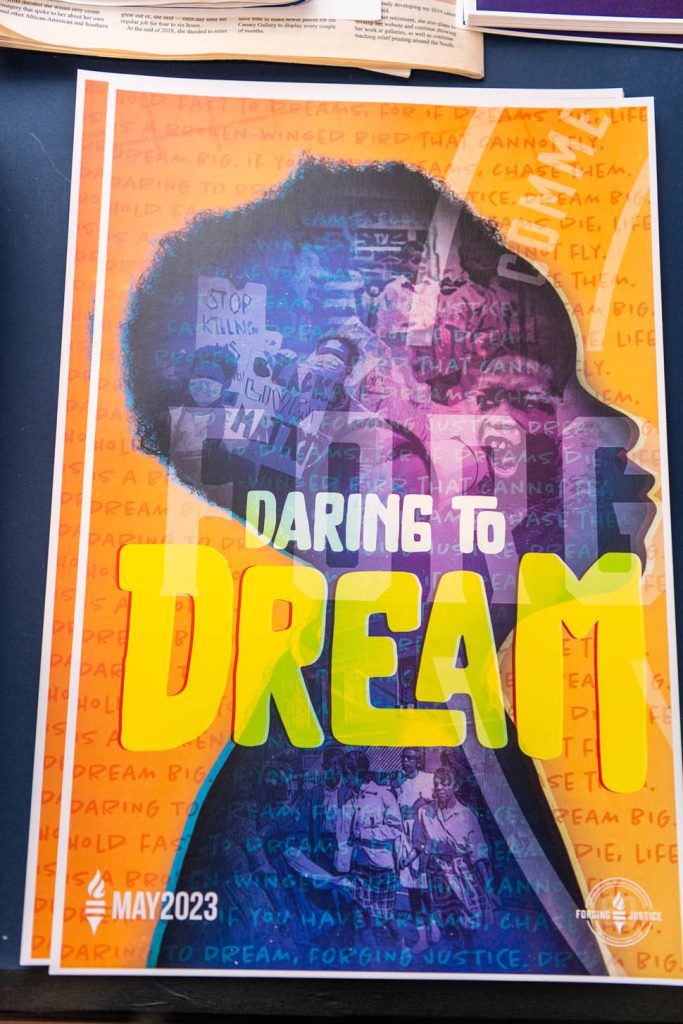

Watts noted that there’s an image that is very personal to him in the poster he devised for May – the month of the famous “Children’s Crusade.”

Applying May’s theme, “Daring to Dream,” Watts took a profile headshot of his youngest son, 9-year-old Isaiah, and filled the space with images of children and young people demonstrating – historic and more contemporary, including from more recent “Black Lives Matter” protests. Behind the silhouette of Isaiah and the other images of children, words scroll across the scene, taken verbatim from the poem “Dreams” by Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes.

In creating the image, Watts said he thought about the courage of the Black children who walked out of their segregated classrooms in May 1963 and converged downtown to march peaceably for equal rights – knowing they faced blasts from firehoses, arrests and potential violence at the hands of a whites-only police force.

“I was wondering: What was on their minds?” Watts said about the youngsters who dared to challenge a power structure that was determined to keep them down.

“It’s still kind of surreal,” Watts said about the entire poster project and the impact it’s having on those who’ve seen them. Not to mention the two designers who put it all together.

As for the final poster, coming in December, it is themed “Money, Power, Respect” and focuses on the ongoing struggle for economic opportunity. Watts and Rudolph said the design is still being tweaked.

“Through this process, we’re still learning,” Watts said.