By Ryan Michaels

The Birmingham Times

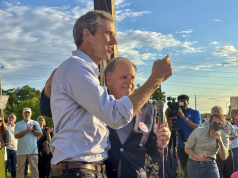

As the finishing touches were being put on the brand-new Fultondale High School, just weeks before this year’s fall semester began, Jefferson County Schools (JEFCOED) Superintendent Walter Gonsoulin, Ed.D., arrived at the site.

Entering the school on a late-July day, Gonsoulin, in a navy blue suit and red tie, pointed out areas where work still needed to be done and chatted with construction workers and the architect in charge, the din of power tools filling the gaps in conversation.

As he eyed the work being done, Dr. G, as those on-site called him, was more focused on his vision for the school system, the second largest in the state behind Mobile County.

Gonsoulin joined the JEFCOED administration team in 2017 as deputy superintendent. Just two years later, when then-Superintendent Craig Pouncey was named president of Coastal Alabama Community College, Gonsoulin took on Pouncey’s role on an interim basis for three months. In November 2019, Gonsoulin was named the permanent superintendent, becoming the first African American to serve permanently in the role.

Building for the Future

Since taking the reins of JEFCOED in 2019, Gonsoulin and his team have focused on a significant number of new facilities, including six newly built elementary schools and the new Fultondale High School, which was scheduled to open on the first day of classes for students—Tuesday, August 8—but has been delayed slightly.

Though all major items passed a building inspection last Thursday (August 3), a few minor things need to be completed before the new facility can be opened. For the first four days of the semester, Fultondale High School students participated in e-learning, while all other schools in the district began in-person learning on Tuesday.

JEFCOED’s capital programs are extensive. Just last month, the system, which has more than 36,000 students, secured Carmon Construction to build a new facility for students in the Jefferson County International Baccalaureate (JCIB) program. Middle school JCIB students have been attending classes at the Pleasant Grove Middle School Campus and high school JCIB students have been at Shades Valley High School, the Irondale Campus.

The new facility, located at the site of the old Fultondale High School, will house both groups under one roof. These facilities and teachers not only provide quality education for students to grow but also are beneficial for area businesses.

JEFCOED graduates about 2,600 students a year, Gonsoulin said, making the system “the workforce for Jefferson County.”

“We already know that a large percentage of those children stay in this area, so while they’re in school, we want to give them opportunities that allow them to be successful in the career market when they leave high school,” the superintendent added.

Some JEFCOED elementary schools are themed around one of three different career pathways: one geared toward science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) careers, one toward performing arts, and another toward global leadership, Gonsoulin said.

At the high school level, JEFCOED last year put in place its “Signature Academies” program, which enables any student in the system to apply to have specialized coursework based around various different career pathways, such as agriscience, cybersecurity, logistics, engineering, and broadcast journalism, among others.

“In Jefferson County, we want to provide as many educational opportunities as possible, so children can go into high-interest, high-wage jobs,” Gonsoulin said, adding that the next step is to “marry” the high school programming to “the business community in Jefferson County” by allowing companies to have access to a database showing the qualifications of JEFCOED students.

Additionally, the superintendent has been working to grow JEFCOED prekindergarten classes, of which the system currently has 42.

“Best Advice I Received”

The Birmingham Times accompanied Gonsoulin during his recent visit to the new Fultondale High School site. While discussing his goals for JEFCOED, he recalled a time he stopped by the home of a girl who had been struggling in his class.

The year was 1991, and it was his first year as a teacher at Jeanerette Elementary School, in Jeanerette, Louisiana.

After knocking on the front door, Gonsoulin sat on the front porch talking with the girl’s mother as the fall sun set into night. During their conversation, Gonsoulin could tell children were in the house, but he never saw the lights come on. Eventually, he realized that the power wasn’t on.

Gonsoulin’s trip was part of a 30-day mission given by his great-grandmother Bertha, who occasionally lived with Gonsoulin during his youth in New Iberia, Louisiana. She recommended that he visit the home of each child in his class within his first month of teaching.

“Find out where they’re living. Find out who they are,” Gonsoulin recalled his great-grandmother saying.

“I was very busy those 30 days, but that was probably the best advice I could have received,” he added.

That initial visit to the girl led Gonsoulin to create an after-school tutoring program at Jeanerette Elementary School—and the student became a regular attendee.

Early Love for Learning

Gonsoulin, 54, is the oldest of six children (he has five sisters: Shannon, Tikeisha, Olympia, Ashley, and Tara) born to Evelyn and Walter Gonsoulin Sr. He believes his age among his siblings contributed to his people skills.

“Definitely, I took a leadership role being the oldest, and still today. It’s taught me how to relate to people who are different. … When you have that many people in a small house, you better know how to relate to folks,” Gonsoulin said.

His father was a taxi driver for 33 years, and his mother worked a variety of jobs but primarily as a chef at different restaurants. While Walter Sr. didn’t live in the home, Gonsoulin said his father was present in his life.

While he was growing up, his family had “very modest means,” he said, meaning education was not only important but “enforced.”

“And by that, I mean, from a very early age, my mother and grandmother sat with me and talked to me about the importance of education, what it could bring and what doors it could open,” Gonsoulin recalled.

Reading became incredibly important for the young Gonsoulin.

“I grew a love for reading very early on,” he said. “When you come from modest means, books become your friends, [books become] your vacations. They allowed me to travel wherever I wanted to travel and to grow in appreciation, in a small town, of what education could truly do.”

Among Gonsoulin’s favorite books at that time were many written by Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, specifically “Green Eggs and Ham.” Moving on from picture books, Gonsoulin gradually was drawn toward biographies of figures like Abraham Lincoln and the poetry of Robert Frost and Edgar Allan Poe.

During second grade at the former Hopkins Street Elementary School in New Iberia is where Gonsoulin first sensed his love for reading. He doesn’t remember if it was a particular book that fueled his passion, but he recalls being acknowledged for his dedication to reading in the third grade.

That day, Gonsoulin said, he and the other students were sitting on the school’s lawn with their teacher, Miss Mitchell, when Gonsoulin received a certificate for his reading development, something he wasn’t expecting.

“At the end, when they called my name, I’ll never forget, I was like, ‘I won an award? All right.’ I just went up and got it. It wasn’t intentional. … I wasn’t reading to get an award. I was reading because it made me happy. I enjoyed it,” Gonsoulin said. “I didn’t even know you could get an award for that at that time.”

In fifth grade, Gonsoulin switched to Park Elementary School in New Iberia before moving onto Anderson Middle School. He graduated from New Iberia Senior High in 1986.

Finding Himself

At 16, Gonsoulin joined the military, inspired by his numerous uncles and cousins who had been in the U.S. Army.

“From fifth grade until 12th grade, that was my summer vacation, going to Fort Polk, Louisiana, staying with my uncle and my aunt and being on the base,” Gonsoulin said.

Being in the National Guard, Gonsoulin could attend school and fulfill the requirements of attending monthly drills and working in the summer.

“I just thought that was the best deal I’d ever heard,” he said.

Right after graduation, Gonsoulin went to basic training. In 1987, he enrolled at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette (ULL), where he first majored in interpersonal counseling and communication because he initially thought he wanted a career in news media. “I had a strong Cajun dialect, so that wasn’t going to work out,” he said.

In 1990, Gonsoulin was deployed during the U.S.’s involvement in the Gulf War in Iraq during a semester of school. He had to put everything on hold and was not able to graduate until 1991, after he had returned home.

Gonsoulin’s first job in education was at Jeanerette Elementary School, where he started teaching sixth grade in 1991. While his degree was not in education, he got an alternative certification to begin teaching. At the same time, though, he started pursuing a second bachelor’s degree, in elementary education, at ULL.

Gonsoulin had completed his six-year requirement for the military to cover the cost of his college education and was trying to figure out his next career move.

“I was seeking opportunities, and a relative who was in education came to me and said, ‘I think you need to think about education,’” he recalled. “I got a chance to visit some of the schools she was supervising and said, “Yes, that’s what I want to do,’ so I went back to school,” Gonsoulin said.

In 1994, Gonsoulin graduated from ULL a second time, this time with a bachelor’s degree in elementary education. That same year, Gonsoulin left Jeanerette to start teaching fifth grade at the former St. Martinville Elementary School, in St. Martinville, Louisiana. Shortly thereafter, he also began pursuing a master’s degree in educational leadership at Southern University (SU) in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, which he earned in 1996.

True Leadership

With his new credentials, Gonsoulin moved into a position as a behavior interventionist at St. Martinville. In that role, Gonsoulin emphasized teaching appropriate behavior instead of being a strict disciplinarian. The job was “very rewarding,” he said.

“I got to know the children on personal levels and realized that I could do one thing for one group and had to do something else for other people,” Gonsoulin added.

He found that it was not difficult to encourage children in appropriate behavior.

“It was very simple. I just found out what they liked. If they liked popcorn parties, I’d say, ‘OK, well, if you do this for three weeks, we’ll have a popcorn party.’ The boys liked going outside and throwing a football. So, [I said], ‘If you, [student], do this, … then every recess, we will have someone out there throwing a football,’” said Gonsoulin, who has two children of his own: Antonio, 33, and Madison, who is currently a JCIB student.

During his year as a behavior interventionist at St. Martinville, he was able to reduce suspensions at the school by 83 percent.

In 1997, Gonsoulin moved to Lee Middle School in Columbus, Mississippi, where he served as a school administrator. During his time in Columbus, Gonsoulin began pursuing his Ph.D. in curriculum and instruction at Mississippi State University in Starkville. In working toward his doctorate, Gonsoulin conducted action research attempting to bridge the “mythical divide,” as he termed it, between community leaders and educators.

“When we surveyed that particular community, there were some who said the school didn’t care about their children, and then there were educators in the community who said people didn’t value education,” he said.

In response to those survey responses, Gonsoulin developed a program that intended to connect university teaching candidates, community members, and families. Churches were particularly important community entities for the action research.

“[In the program], the children would come to the church, and I’d have university teacher candidates attend, so they could work with them, work with the teachers, and get to know those families just like I did,” said Gonsoulin, who earned his Ph.D. in 2001.

Going Above and Beyond

In 2012, Gonsoulin moved to Alabama and served as superintendent of the Fairfield City Schools system. That same year, he also started teaching at Miles College until 2015, when he also started teaching at Samford University in Homewood, Alabama, where he continues teaching.

Early in his career, Gonsoulin learned that the best teachers understand that children, like all people, want to feel cared about.

“People don’t want to know how much you know until they know how much you care,” he said. “So, when you’re dealing with children, I think the first thing is to understand that they’re people, they’re human beings, and they need to know that you care about them. That doesn’t mean giving them sympathy but providing empathy and respecting them as human beings.”

Reaching that understanding also means you can go above and beyond for students, he added.

“When you get to that point, that means, as a teacher, you would do everything it takes to ensure that [each] child is educated and you have an interest in them outside of the classroom,” Gonsoulin said.