By Ryan Michaels

The Birmingham Times

Harper Nichols grew up in a “super, super creative family” and always questioned where she fit in.

Her sisters, Bella, 21, and Zoe, 19, and mother, Lori, a children’s book illustrator, are talented in drawing and painting.

“I can’t draw. I am so bad at drawing. I can’t paint. I can’t do any of that,” Nichols said.

Her father, Ken, and grandfather, Robert, are both photographers—and she, too, eventually found a creative outlet through photography.

“I could create these scenes. I could create these stories. If I could set everything up and take a picture, it got the same message across in the same way, like a painting or a drawing would,” said Nichols, 23, a recent graduate of the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree.

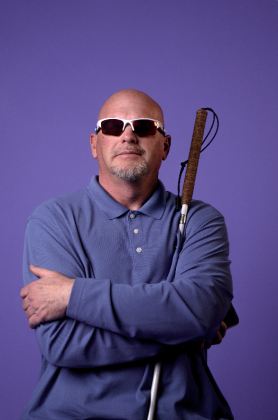

Earlier this year, Nichols, who has cerebral palsy, featured an exhibition of photographs highlighting people who live with physical disabilities. “Strength in Vulnerability – Deconstructing Ableism: Profiles of Success, Determination and Perseverance” opened in January at UAB and explored issues that the community continues to face.

Nichols and filmmaker Ingrid Pfau worked with the UAB School of Health Professions and the National Center on Health, Physical Activity and Disability to create the exhibition.

Capturing Joy

“I think everybody is photographable,” Nichols said. “Photographing people naturally is my go-to. I don’t want to make anybody look like somebody they aren’t. I don’t want to photograph somebody and have them not be recognizable, whether that is in their characteristics or the way they look, but also their personality and their soul.

“That’s the part of the photograph I want to capture—their joy and willingness to be human,” she added. “[I appreciate that they] let me in on that.”

Nichols has a very limited range of motion with her right hand, mostly using it as “a clamp,” she said. “I am very much a functioning one-handed person.”

Cerebral palsy affects people in different ways and can affect body movement, muscle control, muscle coordination, muscle tone, reflex, posture, and balance.

When using a camera, Nichols holds the base to her body with her left hand, as though she were carrying a plate, while using her thumb and index finger to support the lens. To press the shutter button, taking the picture, Nichols uses her middle finger.

Taking photos is “100 percent” supposed to be a two-handed activity, she said. Her method limits her ability to work with different camera models, as well as different lenses, because of the varying weight and dimensions. While Nichols said a left-handed camera could be a significant help, no camera manufacturers really make left-handed models.

(Photographs from Nichols’s exhibition can be viewed in the gallery below)

Place of Comfort

Nichols was first diagnosed with cerebral palsy at about six months of age.

Early in life, she started going to physical and occupational therapy, but she didn’t want to do it anymore around the age of 10 or 11.

“I was like, ‘I’m done with this. This is not fun anymore. I don’t enjoy spending time in physical therapy and occupational therapy, when my friends and my sisters are like outside,’ so I chose to stop doing that,” Nichols said.

Her home was “a place that was comfortable, a place where you felt like you could create, a place where you could express yourself and be independent,” Nichols recalled. “You always had a place to fall back on and people to comfort you and support you in whatever you’re doing.”

While Nichols said she had “no interest” in photography early in life, her interest in the craft of her father and grandfather grew during her time at Homewood High School.

At the nudging of her friend Matthew, Nichols took a course in the subject. In that first class, she found herself enjoying the competition among her friends and other classmates. From that time, Nichols fell in love with photography.

“It was a silly little competition, but I think that competition among my closest friends pushed me a lot to get better. Then I was like, ‘Oh, I’m actually getting OK at this.’ … It was a way to be creatively expressive without having to put pen to paper,” said Nichols, who graduated from Homewood High School in 2018.

“Totally Fine”

Nichols’ disability doesn’t keep her from living a full life, but there can be an internal fear of being perceived as disabled.

“I’m so much more scared of being treated differently that I force myself to act like everything’s normal. I will push it in the opposite direction,” Nichols said.

Still, there have been moments when Nichols found that people could be mean. In middle school, for instance, a couple of students made fun of her on the playground, and then she heard some girls bullying her when she walked back toward the school building. In her mind, she said, “[I was] totally fine with who I am.”

The incident sticks with her today: “I don’t want to speak for everybody with a disability, but as a person with a disability you grow and adapt to the way your body functions and the way your body moves throughout the world. … That should not be a reason to not want to live in the world and be the person you are in the world,” Nichols said.

After the incident, Nichols simply cried when she got home. About a year later, Nichols discovered that the girl who made the comment is the daughter of two deaf parents: “It just made me wonder, ‘How do you have that kind of knowledge of living with and loving people with disabilities and aren’t able to respect other people with disabilities?’”

In August, Nichols will leave for the University of Georgia’s Lamar Dodd School of Art to pursue a Master of Fine Arts degree with a focus on studio art. Moving forward, Nichols is not certain what her next professional move will be—but she knows it will be in the photo world.

![Birmingham’s Well-Dressed: Lawrence Fencher, ‘I Like Taking Worn-Out [Clothes] … Making Something New’](https://www.birminghamtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/LawrenceFrencher-1-238x178.jpg)