In January 1965, Playboy Magazine published Alex Haley’s interview with the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., shortly after King received the Nobel Peace Prize. In that historic interview, King talked about Birmingham more than three dozen times, far more than any other city, including his own native city of Atlanta. The Civil Rights icon mentioned “Letter From Birmingham Jail”, Sixteenth Street Church Bombing and his role as leader of the American Civil Rights movement at that time. Here are excerpts from the interview, which was conducted by author Alex Haley.

Haley: How does the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (S.C.L.C.) select the cities where nonviolent campaigns and demonstrations are to be staged?

King: The operational area of S.C.L.C. is the entire South, where we have affiliated organizations in some 85 cities. Our major campaigns have been conducted only in cities where a request for our help comes from one of these affiliate organizations, and only when we feel that intolerable conditions in that community might be ameliorated with our help. I will give you an example. In Birmingham, one of our affiliate organizations is the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, which was organized by the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, a most energetic and indomitable man. It was he who set out to end Birmingham’s racism, challenging the terrorist reign of Bull Connor. S.C.L.C. watched admiringly as the small Shuttlesworth-led organization fought in the Birmingham courts and with boycotts. Shuttlesworth was jailed several times, his home and church were bombed, and still he did not back down. His defiance of Birmingham’s racism inspired and encouraged Negroes throughout the South. Then, at a May 1962 board meeting of the S.C.L.C. in Chattanooga, the first discussions began that later led to our joining Shuttlesworth’s organization in a massive direct-action campaign to attack Birmingham’s segregation.

Haley: One of the highlights of that campaign was your celebrated “Letter From Birmingham Jail”—written during one of your jail terms for civil disobedience—an eloquent reply to eight Protestant, Catholic and Jewish clergymen who had criticized your activities in Birmingham. Do you feel that subsequent events have justified the sentiments expressed in your letter?

King: I would say yes. Two or three important and constructive things have happened which can be at least partially attributed to that letter. By now, nearly a million copies of the letter have been widely circulated in churches of most of the major denominations. It helped to focus greater international attention upon what was happening in Birmingham. And I am sure that without Birmingham, the March on Washington wouldn’t have been called—which in my mind was one of the most creative steps the Negro struggle has taken. The March on Washington spurred and galvanized the consciences of millions. It gave the American Negro a new national and international stature. The press of the world recorded the story as nearly a quarter of a million Americans, white and Black, assembled in grandeur as a testimonial to the Negro’s determination to achieve freedom in this generation.

It was also the image of Birmingham which, to a great extent, helped to bring the Civil Rights Bill into being in 1963. Previously, President Kennedy had decided not to propose it that year, feeling that it would so arouse the South that it would meet a bottleneck. But Birmingham, and subsequent developments, caused him to reorder his legislative priorities.

One of these decisive developments was our last major campaign before the enactment of the Civil Rights Act—in St. Augustine, Florida. We received a plea for help from Dr. Robert Hayling, the leader of the St. Augustine movement. St. Augustine, America’s oldest city, and one of the most segregated cities in America, was a stronghold of the Ku Klux Klan and the John Birch Society. Such things had happened as Klansmen abducting four Negroes and beating them unconscious with clubs, brass knuckles, ax handles and pistol butts. Dr. Hayling’s home had been shot up with buckshot, three Negro homes had been bombed and several Negro night clubs shotgunned. A Negro’s car had been destroyed by fire because his child was one of the six Negro children permitted to attend white schools. And the homes of two of the Negro children in the white schools had been burned down. Many Negroes had been fired from jobs that some had worked on for 28 years because they were somehow connected with the demonstrations. Police had beaten and arrested Negroes for picketing, marching and singing freedom songs. Many Negroes had served up to 90 days in jail for demonstrating against segregation, and four teenagers had spent six months in jail for picketing. Then, on February seventh of last year, Dr. Hayling’s home was shotgunned a second time, with his pregnant wife and two children barely escaping death; the family dog was killed while standing behind the living-room door. So S.C.L.C. decided to join in last year’s celebration of St. Augustine’s gala 400th birthday as America’s oldest city—by converting it into a nonviolent battleground. This is just what we did.

Haley: But isn’t it true, Dr. King, that during this and other “nonviolent” demonstrations, violence has occurred—sometimes resulting in hundreds of casualties on both sides?

King: Yes, in part that is true. But what is always overlooked is how few people, in ratio to the numbers involved, have been casualties. An army on maneuvers, against no enemy, suffers casualties, even fatalities. A minimum of whites have been casualties in demonstrations solely because our teaching of nonviolence disciplines our followers not to fight even if attacked. A minimum of Negroes are casualties for two reasons: Their white oppressors know that the world watches their actions, and for the first time they are being faced by Negroes who display no fear.

Haley: But the kind of extremism for which you’ve been criticized has to do not with love, but with your advocacy of willful disobedience of what you consider to be “unjust laws.” Do you feel you have the right to pass judgment on and defy the law—nonviolently or otherwise?

King: Yes—morally, if not legally. For there are two kinds of laws: man’s and God’s. A man-made code that squares with the moral law, or the law of God, is a just law. But a man-made code that is inharmonious with the moral law is an unjust law. And an unjust law, as St. Augustine said, is no law at all. Thus a law that is unjust is morally null and void, and must be defied until it is legally null and void as well. Let us not forget, in the memories of 6,000,000 who died, that everything Adolf Hitler did in Germany was “legal,” and that everything the Freedom Fighters in Hungary did was “illegal.” In spite of that, I am sure that I would have aided and comforted my Jewish brothers if I had lived in Germany during Hitler’s reign, as some Christian priests and ministers did do, often at the cost of their lives. And if I lived now in a Communist country where principles dear to the Christian’s faith are suppressed, I know that I would openly advocate defiance of that country’s antireligious laws—again, just as some Christian priests and ministers are doing today behind the Iron Curtain. Right here in America today there are white ministers, priests and rabbis who have shed blood in the support of our struggle against a web of human injustice, much of which is supported by immoral man-made laws.

Haley: Segregation laws?

King: Specifically, court injunctions. Though the rights of the First Amendment guarantee that any citizen or group of citizens may engage in peaceable assembly, the South has seized upon the device of invoking injunctions to block our direct-action civil rights demonstrations. When you get set to stage a nonviolent demonstration, the city simply secures an injunction to cease and desist. Southern courts are well known for “sitting on” this type of case; conceivably a two- or three-year delay could be incurred. At first we found this to be a highly effective subterfuge against us. We first experienced it in Montgomery when, during the bus boycott, our car pool was outlawed by an injunction. An injunction also destroyed the protest movement in Talladega, Alabama. Another injunction outlawed the oldest civil rights organization, the NAACP, from the whole state of Alabama. Still another injunction thwarted our organization’s efforts in Albany, Georgia. Then in Birmingham, we felt that we had to take a stand and disobey a court injunction against demonstrations, knowing the consequences and being prepared to meet them—or the unjust law would break our movement.

We did not take this step hastily or rashly. We gave the matter intense thought and prayer before deciding that the right thing was being done. And when we made our decision, I announced our plan to the press, making it clear that we were not anarchists advocating lawlessness, but that in good conscience we could not comply with a misuse of the judicial process in order to perpetuate injustice and segregation. When our plan was made known, it bewildered and immobilized our segregationist opponents. We felt that our decision had been morally as well as tactically right—in keeping with God’s law as well as with the spirit of our nonviolent direct-action program.

Haley: Whom do you include among “the irresponsible few”?

King: I include those who preach racism and commit violence; and those who, in various cities where we have sought to peacefully demonstrate, have sought to goad Negroes into violence as an excuse for violent mass reprisal. In Birmingham, for example, on the day it was flashed about the world that a “peace pact” had been signed between the moderate whites and the Negroes, Birmingham’s segregationist forces reacted with fury, swearing vengeance against the white businessmen who had “betrayed” them by negotiating with Negroes. On Saturday night, just outside of Birmingham, a Ku Klux Klan meeting was held, and that same night, as I mentioned earlier, a bomb ripped the home of my brother, the Reverend A. D. King, and another bomb was planted where it would have killed or seriously wounded anyone in the motel room which I had been occupying. Both bombings had been timed just as Birmingham’s bars closed on Saturday midnight, as the streets filled with thousands of Negroes who were not trained in nonviolence, and who had been drinking. Just as whoever planted the bombs had wanted to happen, fighting began, policemen were stoned by Negroes, cars were overturned and fires started.

Haley: Do you feel that the Negro church has come any closer to “the projection of a social gospel” in its commitment to the cause?

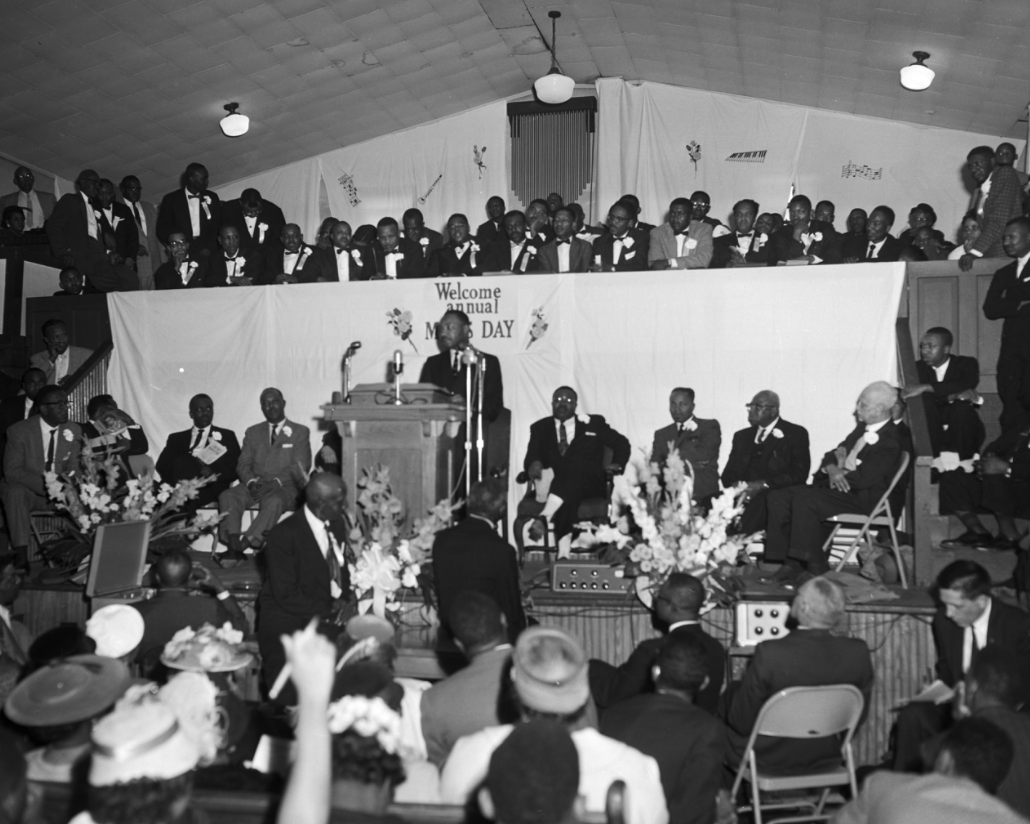

King: I must say that when my Southern Christian Leadership Conference began its work in Birmingham, we encountered numerous Negro church reactions that had to be overcome. Negro ministers were among other Negro leaders who felt they were being pulled into something that they had not helped to organize. This is almost always a problem. Negro community unity was the first requisite if our goals were to be realized. I talked with many groups, including one group of 200 ministers, my theme to them being that a minister cannot preach the glories of heaven while ignoring social conditions in his own community that cause men an earthly hell. I stressed that the Negro minister had particular freedom and independence to provide strong, firm leadership, and I asked how the Negro would ever gain freedom without his minister’s guidance, support and inspiration. These ministers finally decided to entrust our movement with their support, and as a result, the role of the Negro church today, by and large, is a glorious example in the history of Christendom. For never in Christian history, within a Christian country, have Christian churches been on the receiving end of such naked brutality and violence as we are witnessing here in America today. Not since the days of the Christians in the catacombs has God’s house, as a symbol, weathered such attack as the Negro churches.

I shall never forget the grief and bitterness I felt on that terrible September morning when a bomb blew out the lives of those four little, innocent girls sitting in their Sunday-school class in the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. I think of how a woman cried out, crunching through broken glass, “My God, we’re not even safe in church!” I think of how that explosion blew the face of Jesus Christ from a stained-glass window. It was symbolic of how sin and evil had blotted out the life of Christ. I can remember thinking that if men were this bestial, was it all worth it? Was there any hope? Was there any way out?

Haley: Do you still feel this way?

King: No, time has healed the wounds—and buoyed me with the inspiration of another moment which I shall never forget: when I saw with my own eyes over 3000 young Negro boys and girls, totally unarmed, leave Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church to march to a prayer meeting—ready to pit nothing but the power of their bodies and souls against Bull Connor’s police dogs, clubs and fire hoses. When they refused Connor’s bellowed order to turn back, he whirled and shouted to his men to turn on the hoses. It was one of the most fantastic events of the Birmingham story that these Negroes, many of them on their knees, stared, unafraid and unmoving, at Connor’s men with the hose nozzles in their hands. Then, slowly the Negroes stood up and advanced, and Connor’s men fell back as though hypnotized, as the Negroes marched on past to hold their prayer meeting. I saw there, I felt there, for the first time, the pride and the power of nonviolence.

Another time I will never forget was one Saturday night, late, when my brother telephoned me in Atlanta from Birmingham—that city which some call “Bombingham”—which I had just left. He told me that a bomb had wrecked his home, and that another bomb, positioned to exert its maximum force upon the motel room in which I had been staying, had injured several people. My brother described the terror in the streets as Negroes, furious at the bombings, fought whites. Then, behind his voice, I heard a rising chorus of beautiful singing: “We shall overcome.” Tears came into my eyes that at such a tragic moment, my race still could sing its hope and faith.

Haley: Do you feel that the African nations, in turn, should involve themselves more actively in American Negro affairs?

King: I do indeed. The world is now so small in terms of geographic proximity and mutual problems that no nation should stand idly by and watch another’s plight. I think that in every possible instance Africans should use the influence of their governments to make it clear that the struggle of their brothers in the U.S. is part of a world-wide struggle. In short, injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere, for we are tied together in a garment of mutuality. What happens in Johannesburg affects Birmingham, however indirectly. We are descendants of the Africans. Our heritage is Africa. We should never seek to break the ties, nor should the Africans.

Haley: In conspicuous contrast, according to a recent poll conducted by Ebony, only one Negro in ten has ever participated physically in any form of social protest. Why?

King: It is not always sheer numbers that are the measure of public support. As I see it, every Negro who does participate represents the sympathy and the moral backing of thousands of others. Let us never forget how one photograph, of those Birmingham policemen with their knees on that Negro woman on the ground, touched something emotionally deep in most Negroes in America, no matter who they were. In city after city, where S.C.L.C. has helped to achieve sweeping social changes, it has been not only because of the quality of its members’ dedication and discipline, but because of the moral support of many Negroes who never took an active part. It’s significant, I think, that during each of our city struggles, the usual average of crimes committed by Negroes has dropped to almost nothing.

But it is true, undeniably, that there are many Negroes who will never fight for freedom—yet who will be eager enough to accept it when it comes. And there are millions of Negroes who have never known anything but oppression, who are so devoid of pride and self-respect that they have resigned themselves to segregation. Other Negroes, comfortable and complacent, consider that they are above the struggle of the masses. And still others seek personal profit from segregation.

Haley: In the meanwhile, you are now the universally acknowledged leader of the American civil rights movement, and chief spokesman for the nation’s 20 million Negroes. Are there ever moments when you feel awed by this burden of responsibility, or inadequate to its demands?

King: One cannot be in my position, looked to by some for guidance, without being constantly reminded of the awesomeness of its responsibility. I live with one deep concern: Am I making the right decisions? Sometimes I am uncertain, and I must look to God for guidance. There was one morning I recall, when I was in the Birmingham jail, in solitary, with not even my lawyers permitted to visit, and I was in a nightmare of despair. The very future of our movement hung in the balance, depending upon capricious turns of events over which I could have no control there, incommunicado, in an utterly dark dungeon. This was about ten days after our Birmingham demonstrations began. Over 400 of our followers had gone to jail; some had been bailed out, but we had used up all of our money for bail, and about 300 remained in jail, and I felt personally responsible. It was then that President Kennedy telephoned my wife, Coretta. After that, my jail conditions were relaxed, and the following Sunday afternoon—it was Easter Sunday—two S.C.L.C. attorneys were permitted to visit me. The next day, word came to me from New York that Harry Belafonte had raised $50,000 that was available immediately for bail bonds, and if more was needed, he would raise that. I cannot express what I felt, but I knew at that moment that God’s presence had never left me, that He had been with me there in solitary.

I subject myself to self-purification and to endless self-analysis; I question and soul-search constantly into myself to be as certain as I can that I am fulfilling the true meaning of my work, that I am maintaining my sense of purpose, that I am holding fast to my ideals, that I am guiding my people in the right direction. But whatever my doubts, however heavy the burden, I feel that I must accept the task of helping to make this nation and this world a better place to live in—for all men, Black and white alike.

I never will forget a moment in Birmingham when a white policeman accosted a little Negro girl, seven or eight years old, who was walking in a demonstration with her mother. “What do you want?” the policeman asked her gruffly, and the little girl looked him straight in the eye and answered, “Fee-dom.” She couldn’t even pronounce it, but she knew. It was beautiful! Many times when I have been in sorely trying situations, the memory of that little one has come into my mind, and has buoyed me.

Similarly, not long ago, I toured in eight communities of the state of Mississippi. And I have carried with me ever since a visual image of the penniless and the unlettered, and of the expressions on their faces—of deep and courageous determination to cast off the imprint of the past and become free people. I welcome the opportunity to be a part of this great drama, for it is a drama that will determine America’s destiny. If the problem is not solved, America will be on the road to its self-destruction. But if it is solved, America will just as surely be on the high road to the fulfillment of the founding fathers’ dream, when they wrote: “We hold these truths to be self evident.…”

For the full interview, visit here