By Ryan Michaels

The Birmingham Times

No one will be sleeping in any of the prototype structures that were built as part of a city-funded, community-led effort to provide temporary housing and services for homeless residents of Birmingham during The World Games (TWG) 2022, according to Bruce Lanier, an architect who has worked on the project.

The World Games will be held in Birmingham and area venues from July 7-17.

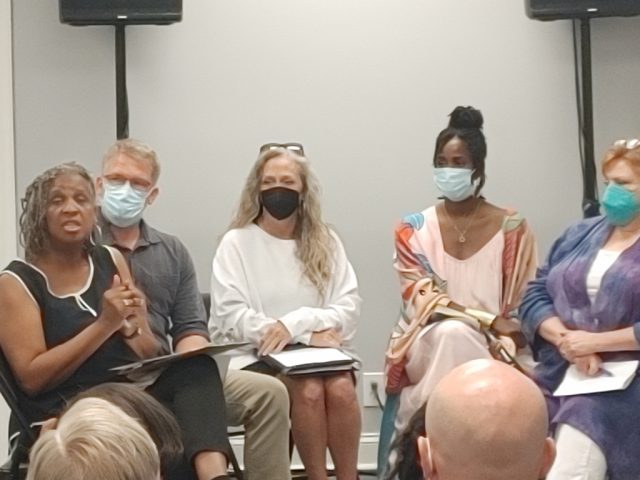

Following public outcry about the structures, representatives of five organizations involved in the “Compassion Project” met on Thursday at Faith Chapel Care Center in the Smithfield neighborhood to provide clarity about the project.

Watch on TikTok

Representatives who spoke on behalf of the Compassion Project on Thursday were Debra Blaylock, executive liaison, ministerial/community at Faith Chapel; Michelle Farley, executive director of One Roof, the official continuum of care organization for Jefferson County; Kelly Greene, executive director of Food for Our Journey, which provides food for homeless residents of Birmingham; Bruce Lanier, an architect representing the Alabama Center for Architecture, and Kay Simmons, founder of God’s Loving Hands Ministries, which provides entertainment and services for homeless people in Birmingham.

The meeting was attended by about 30 residents and community activists.

Lanier, part of the Alabama Center for Architecture, said the shelters would only be for use at night and will have air conditioning, locking keypad doors, a light, cots with sleeping mats and electrical outlets. To assemble the shelters before the Games was an “extremely ambitious goal,” Lanier said.

“I’m here to tell you that we did not meet that goal. While occupancy is something that we had hoped to achieve by the World Games, this is not a World Games project, nor is it a project that was intended to follow the World Games timeline,” he said.

The shelters are still planned to be used after TWG2022 following further revision and feedback, Lanier said. When the architects involved with the project decide on a design suitable for use by people, the structures will be built and housed on an as-yet-unknown site partnered with the Compassion Project, Lanier said.

He also stressed that the Compassion Project is not a project of the city of Birmingham, TWG2022 or law enforcement agencies.

Farley said the “micro-shelter” approach to housing homeless people is not a permanent solution.

“There is no way that these tiny micro-shelters can provide dignity for people. They need permanent supportive housing, but the money has not been there for the type of safe, decent and affordable housing that we need. This is a stopgap. This is not meant to be the be-all and end-all to homelessness. This is simply an option,” Farley said.

While permanent housing is not available for homeless residents of the city, micro-shelters can provide temporary sanctuary, Farley said.

“Our folks are much more likely to be victims of crime than they are to perpetuate crime. If we don’t have permanent housing for them. We need some barrier between them and those who would harm. This is not a perfect answer,” Farley said.

Kay Simmons, founder of God’s Loving Hand Ministries, one of the partnered organizations in the Compassion Project, said the project was never “solely about sleeping” but intended to provide for and include homeless residents of Birmingham during the Games.

Simmons and other representatives of the project also said that whether homeless residents took part in the services was a choice for each of those residents to make.

“This was never about force…That was never a conversation from anyone in the Compassion Project. People actually took time to go and speak in the park with our [homeless] friends, to some of the shelters, did surveys to really see exactly what they wanted,” Simmons said.

During a question-and-answer session, Cara McClure, a single mom who was homeless between 2008 and 2011 and a founder of Black Lives Matter Birmingham, said seeing the prototype structures was “triggering” for her.

“I could not imagine me and my son in that structure. It looks scary, and I would not like being in the structure and not knowing what’s happening around me. I wouldn’t want to be in a fenced in space. It gives me the idea of jail,” McClure said.

With further community engagement, the project would improve, McClure said.

“I just feel your heart and your passion, and I’m so glad that you brought this together, and I’ll gladly open up the conversation,” McClure said.

Blaylock emphasized that the amount of time that architects had to work on the shelters was limited and that the team consulted with the homeless population in Birmingham but conceded they may not have gotten enough feedback.

The shelters are an experiment that requires feedback, Lanier said.

“The reason that you try things is to get a response, and if the response is that people who’ve experienced homelessness personally don’t think this is something they would use, then that’s something I want to understand more. I think it matters,” Lanier said.

“Learning is not failure. Learning is progress,” he added.

Faith Chapel Care Center, 921 2nd Ave N, Birmingham AL 35203, can be reached at 205-785-9673