By Caroline Gazzara-McKenzie

University of Alabama

It was 1963 and Birmingham was going through a racial revolution. Demonstrations and peaceful protests against the city’s strict segregation laws were being met by police with arrests and violence. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was in Atlanta and agreed to travel to Birmingham to support the movement. Eight white clergyman had just published an open letter on April 12 urging restraint by the protestors.

King was arrested later that day and spent 11 days in the Birmingham City Jail, including time in solitary confinement. He wasn’t allowed to make a phone call.

While there, he wrote notes in the margins of The Birmingham News, reaching out to most of the eight white clergymen. Those notes, passed through a jail trustee and then to King’s lawyer, were transcribed by a secretary and compiled into a letter that would be sent to seven of the eight clergymen.

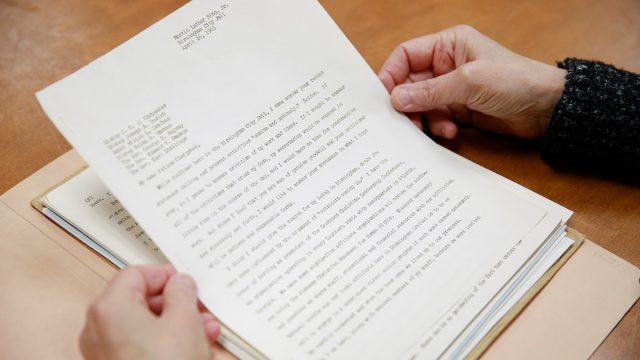

The letter was copied by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the civil rights organization founded by King and other leaders, and mailed to clergymen throughout the state. One of those recipients was Methodist minister Joe Higginbotham of Centre. In 2006, his wife, Ann, donated the letter to the University of Alabama. Recently, University Library Special Collections digitized the 21-page Letter from Birmingham Jail, offering everyone the opportunity to read it and experience its impact.

Lorraine Madway, professor and associate dean for special collections, said the department will continue to study the letter and the envelope it was mailed in. She said the letter is an important piece of history that helped shape the civil rights movement.

“It is significant that the letters were sent to clergymen who were moderates at that time,” Madway said. “The thrust of much of this letter is to criticize those who were advocating moderation at a time when the struggle demanded direct action – direct nonviolent action.”

Dated April 16, 1963, King wrote that he came to Birmingham as president of the SCLC to aid affiliate groups before being arrested. He famously said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” and asked the clergymen to reflect on the city’s history of segregation. He provided compelling examples of violence and desegregation promises unkept, while questioning why negotiations with city officials weren’t working.

“King is an effective persuader,” Madway said. “He is saying to the clergymen that ‘What I’m sharing with you is steeped in Christian and Jewish teachings.’ He’s quoting the Hebrew Bible as well as New Testament material and saying, ‘You are clergymen, but you’re not honoring your own tradition.’”

The letter offers four principles to nonviolent action: the collection of facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self-purification; and direct action.

He closed the letter stating that one day, the South will recognize its real heroes: those who stood up courageously for change. The seven clergymen the letter was sent to were urged to reflect on their past decisions and move forward toward a world free of segregation.

View the letter in the university’s collection here.

This story was originally posted by the University of Alabama.