By Solomon Crenshaw Jr.

Alabama NewsCenter

Phyllis Palmer remembers laughing when her brother talked about being buried at Elmwood Cemetery.

The year was 1968 and the United States was involved in the Vietnam War. Bill Terry Jr. would soon ship out as a private in the Army.

And he made his wishes known.

“When Bill left, he said that if he didn’t come back home, make it back safely, that he would like to be buried at Elmwood,” Palmer said. “Of course, back then that was impossible. We kind of laughed about it.”

Did a 13-year-old Palmer laugh because she couldn’t fathom her brother dying? Or because the reality of Blacks and Elmwood was too real?

In hindsight, Palmer remembers thinking her brother was joking.

“Yeah, I did,” she said. “Like I said, we laughed about it.”

But Terry was gravely committed to his desire, repeating it in a letter to family before he was indeed killed in battle on July 3, 1969.

During Black History Month, Rosa Parks is remembered for taking a stand by sitting on a Montgomery bus. Would-be diners took a stand by taking seats at lunch counters and countless people marched so they and others could step to the polls.

Likely few remember the man who took a step after he had taken his last.

Terry, who was posthumously promoted to corporal, is the Army soldier who broke the color barrier that extended to the grave. Before his stance, Blacks could not be buried in “white” cemeteries.

Prior to going to Vietnam and in a subsequent letter to his family, Terry said that if he were killed fighting for his country that he wanted to be buried in Elmwood, the 412-acre cemetery on the west end of Sixth Avenue South at Martin Luther King Jr. Drive in Birmingham.

Terry, who was born on Feb. 23, 1949, and would now be 73, will be remembered during Sunday service at Our Lady of Fatima Catholic Church, his family’s church, which was integral in efforts to achieve his final wish.

That wish was initially denied by owners of Elmwood and he was buried at Shadow Lawn.

As a student at Samford University in December 2001, David Murphy wrote a research paper on Terry – “Discrimination Among the Dead: A Narrative and Contextual Analysis of Bill Terry’s Integration of Elmwood Cemetery.” He wrote about and others remember the role of Father Eugene Ferrell, the Terry family pastor at Our Lady of Fatima. Ferrell was a major spokesman and activist for the cause.

Murphy wrote that while Ferrell had been assigned to Birmingham previously as a teacher at Immaculate High School at Our Lady of Fatima on his third assignment from 1962 to 1965, his return to Birmingham for his fifth assignment in 1966 was his first experience as the senior pastor of a church.

Guidance

It was with Ferrell’s guidance that Terry’s mother and widow sued Elmwood Cemetery in federal court on July 25, 1969 with the aid of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and attorney Oscar W. Adams to seek an end to the discrimination policy, $10,000 in damages, $500 to remove Terry’s body from Shadow Lawn and $1,500 in attorney’s fees. U.S. District Judge Seybourn Lynne ruled that Elmwood was legally obligated to sell burial plots to any U.S. citizen, “without regard to race or color.”

Douglass Moorer grew up with Terry. He was heading to college when Terry was heading to the Army. The childhood friends agreed they would get together after four years “and tell lies about all the stuff we had endured those four years.”

“A little less than six months later, I got a letter from my mother, informing me Bill had been killed in Vietnam.”

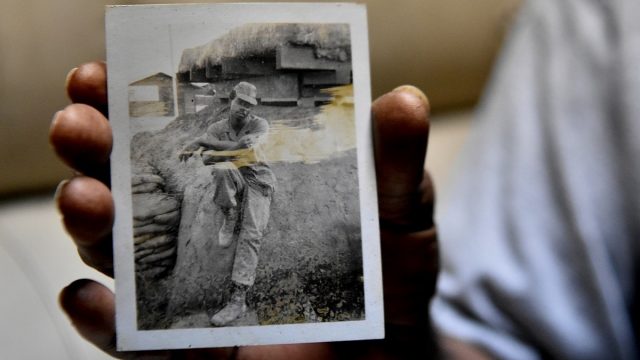

Charlie Woodruff was present when Terry lost his life in a firefight with Viet Cong. He was also present when his friend penned the letter that repeated his desire to be buried at Elmwood.

“I met Bill Terry at the airport, both of us on our way to Vietnam,” the 76-year-old Wenonah native and Childersburg resident said. “As a matter of fact, when we got there, we wound up in the same company and in the same platoon. I carried the M-60 and he carried the grenade launcher.

“We were combat soldiers,” Woodruff said. “We’d been on a whole lot of search-and-destroy missions, but he got killed on the third of July.”

Moorer, now a deacon at Our Lady of Fatima, said his friend and his church – under the leadership of Ferrell – wanted to see things change.

“Bill’s legacy is not just here at Our Lady of Fatima, or here in Birmingham, Alabama, or at Elmwood Cemetery,” Moorer said. “There are people who experience his legacy without even knowing it, everywhere in the country.

“Because of what happened here with Bill Terry, that cemetery and those cemeteries even in California now bury Blacks in the same cemetery as whites,” he continued. “The legacy of Bill Terry goes far beyond these walls (of the church), far beyond just being local. Bill’s desire to be buried at Elmwood was something that changed all of the landscape here in this country in an area of racism that we never would have looked at.”

Final Resting Place

Terry’s body was exhumed from Shadow Lawn on Jan. 3, 1970 and a processional estimated at 1,000 people marched more than half a mile to his final resting place. An article in the Jan. 4, 1970 edition of The Birmingham News said Farrell spoke at the church before the march to Elmwood.

“We are gathered today, not for a funeral service,” he said. “It is not a time for mourning, but rejoicing. We rejoice that we on Earth have been able to respond to his last will.”

Attorney U.W. Clemon was part of the legal team that fought for the Terry family.

“We were very gratified at the judge’s decision because we knew what it meant,” he said. “Elmwood was such a citadel of segregation. To have torn down that wall was important to us and we felt good about it.

“(Terry) had a premonition just before he was killed and he wrote a letter to his parents and told them that if he were killed, he wanted to be buried at Elmwood.”

Murphy, now working in hospital chaplaincy, said, “That’s an interesting thing for a young man to say, thinking about going overseas and fighting in Vietnam. One of the things he thinks to tell his loved ones before he goes is, ‘If I come home in a box, I want you to put me in that cemetery over there.’ And he knew it was segregated. It’s a fascinating thing to think about, his mindset on that.”

While the home where Terry grew up has been torn down, a monument is in the works to remember his church and his sacrifice. Paula Stanton chairs the Titusville Marker Committee, whose aim is to erect markers at historic locations in the community.

Our Lady of Fatima has been tabbed for a marker.

“The committee recognized the role that the church played in the desegregation of Elmwood Cemetery,” Stanton said. “That was one of the reasons why we selected it as one of the sites here in Titusville to honor and to place historic markers. The marker committee wanted to honor (the church’s efforts to have Terry moved to Elmwood) by putting a marker at the church that explained exactly what happened.

“So often people living right here don’t know a whole lot about this community,” she continued. “We thought this was a way that we could inform and honor what had happened.”

Roderick Palmer, Phyllis’ husband, said his brother-in-law’s story is powerful.

“History like that should be taught and told because it’s very important,” he said. “The guy sacrificed his life for the country and this is what he had to go through to get put down there with the white people.”

This story originally appeared on www.alabamanewscenter.com