By Barnett Wright

The Birmingham Times

Standing before a room packed with executives, elected officials, and everyday people, Randall L. Woodfin noticed something he hadn’t since being elected mayor of Birmingham a little more than five years ago.

“I was overwhelmed in the moment,” said the mayor, recalling the late-January day that he was in the Protective Stadium Club in downtown Birmingham for the launch of the upcoming United States Football League (USFL) season.

“There were genuine hugs and high fives,” Woodfin continued. “That was a genuine collective moment [that] we won. The city won. The county won. State legislators, independents, Democrats, Republicans, Black, white, core of the city, urban, suburban—we won!”

The mayor, who was on the program as one of the featured speakers, wasn’t the only person in the room of nearly 400 who sensed the victory. Sen. J.T. “Jabo” Waggoner, a Republican from Vestavia Hills, who turned 85 in January, told the crowd, “I’ve probably lived in this community longer than the vast majority of people in this room, and this is probably the most exciting moment in my lifetime. This is a huge day, and there’s a lot of excitement in this room.”

Asked later about the event, Waggoner, chairman of the powerful Senate Rules Committee in the Alabama State Legislature, said, “That was living proof of what can happen if everybody works together. We did, and look at the results.”

Destination: Birmingham

Thanks to cooperation among leaders at all levels, those results in the Birmingham metro area are numerous and continue to grow. The USFL will kick off its regular season at Protective Stadium in April. The World Games 2022 (TWG 2022) events will take place at various local venues in July. The NBA G League’s Squadron currently plays its home games at the newly renovated Birmingham-Jefferson Convention Complex (BJCC) Legacy Arena.

In addition, Birmingham will host a series of Southwest Athletic Conference (SWAC’s) football games at Legion Field each season for the next three years; the NCAA Division I Men’s Basketball Tournament’s first and second rounds in 2023; and the World Police and Fire Games and NCAA Division I Women’s Basketball Tournament’s Elite 8 in 2025.

“You don’t get those economic development opportunities and projects without cooperation, and there have been a lot of people toiling in the vineyards for a long time to get [the city] to this point,” said Ann Florie, former executive director of Leadership Birmingham, who has held numerous leadership positions in the region.

The spirit of working together is “essential” for the area, she added: “I think the [recently opened $200 million Protective Stadium] is a perfect example of the realization that things that happen are important. No matter where they are, they have an impact on the whole region, and the economy is truly regional.”

In a series of interviews with The Birmingham Times over the last month, Woodfin, Waggoner, Florie, and others say area leaders have overcome distrust and worked collaboratively to make metro Birmingham one of the premiere global markets for events.

“We could not have had the [TWG 2022] without everyone being on board,” said Birmingham City Councilor Hunter Williams. “We needed help from [Jefferson County] and the state to put this on—and we’ve gotten it from both. Same thing with building Protective Stadium, renovating Legacy Arena, bringing in the USFL. … I think we’re now starting to see economic development and tourism as a team effort, where it’s been completely siloed [in the past].”

The economic impact of these events totals hundreds of millions of dollars. The USFL’s debut season in April and TWG 2022 in July, for instance, will bring significant revenue to the region—and it was possible only because of teamwork among regional leaders, said Birmingham City Council President Wardine Alexander.

“It’s always exciting when we all can work for one common goal,” she said. “In this case, it was truly the economic development for this area, between the county and the city, and providing this opportunity for our residents and for the fans that will be visiting.”

State Rep. Merika Coleman, a Democrat from Pleasant Grove, added, “Most of the large-scale projects coming to the area take regional cooperation. … When you’re bringing in new industry, they’re looking at lots of different factors. But having all of the elected officials, including all of the partners, on board—that is a plus.

Jefferson County Commission President Jimmie Stephens said, “When you communicate, cooperate, and coordinate, and compartmentalize those issues you don’t agree on, you reach a common ground to move the community forward. … We’ve found out that that doesn’t just work in politics, in government, it works throughout the community. The more we’re able to utilize that, the better off we are, the more unified we are, the more successful we are.”

“Cooperation”

When Woodfin assumed the role of mayor in Birmingham nearly five years ago, he was “hell bent” on one “C” word, in particular—cooperation.

“I knew consolidation was off the table,” he said. “But cooperation [was a possibility]. … We first identified low-hanging fruit and then moved toward things that we could do, that have the same interests.

“I think people forget that the first thing was about neighborhoods. There was an economic play in 2017, [when I was first elected]. It was centered around a 40-year conversation about a stadium. A zillion starts and stops, at least two groundbreakings. So, everybody came together—the city of Birmingham, the Mayor-Council, [Jefferson] County Commissioners, the Jefferson County delegation [in Montgomery, Alabama], the state of Alabama, the private sector, the University of Alabama at Birmingham—and showed that when we all work together, something can finally get done.”

For Woodfin, cooperation meant building a coalition across party lines and jurisdictions when it came time to build Protective Stadium and attract the USFL.

“I started calling the mayor of Hoover, the mayor of Mountain Brook, Sen. Waggoner,” he said. “I started calling city councilors. I started calling other mayors in other areas of the county, legislators in the county, County Commissioner Shelia Tyson. … When you start communicating with people, you start understanding their needs and desires, as well as your similar interests, and then you start working toward that.”

As a result, several bonds were strengthened, such as the one between Woodfin and Hoover Mayor Frank Brocato.

“We have just had a really incredible bond and developed an absolute, … just a really nice relationship over the last four years,” Brocato said. “We talk often, we share ideas with one another, we work on ways to improve the entire metropolitan area.”

Woodfin also focused on his relationships with Waggoner and Sen. Rodger Smitherman, a Democrat who represents Birmingham in the State Legislature. Birmingham lacks home rule—the power and authority to run its own affairs and must rely on the Legislature to get a lot of things done, so having Smitherman and Waggoner as allies has made a difference.

“I’m depending on legislators in Montgomery to create state laws for a local bill,” Woodfin said. “To help Birmingham, you’ve got to play in the sandbox with people who may see things differently. … Their values may be different, their priorities may be different, their politics may be different, their party is different, but I still have to get wins for the people in this community.”

The lines of communication are a two-way street for Waggoner and Woodfin, who often call one another.

“It works both ways,” the state senator said. “He’s the new guy on the block, … the mayor of our mother city. What we do in Montgomery affects our mother city, and Mayor Woodfin is its leader, so we’re going to work together. … [That] has paid off for Birmingham and for our entire community.”

Smitherman, Waggoner’s counterpart in the Legislature, agreed: “It means all the world to see examples of cooperation, of people working together. That’s how you start to get things moving. It’s easy when two people are pushing something the same way. … You just have to have an open mind. You have to see things from both sides and perspectives and communicate.”

Many of those working in tandem to move the Birmingham metro area forward are from different sides of the aisle and represent several different municipalities.

“We’ve built trust—‘We,’ not ‘I,’” Woodfin said.

“I came in and had a very clear vision of what I wanted to see for this community, all 99 neighborhoods in the city, not just for neighborhood revitalization but for our economic identity. I think you can get people to come together on the economic identity piece,” the mayor added. “We will not always agree on everything, but you build trust by first opening up the lines of communication and then communicating consistently, talking about things you want to agree about or work on together.”

“Good Neighbor Pledge”

Woodfin and others, including Jefferson County Commissioner Steve Ammons and Homewood City Councilor Jennifer Andress, point to a “historic” moment when local officials began to trend in the direction of working together: the anti-poaching agreement, called the “Good Neighbor Pledge,” signed in 2019. As part of the agreement, 22 area mayors vowed that they would not lure businesses away from other cities. They also agreed that they would not provide incentives for businesses relocating from one city to another.

“This agreement was the catalyst for much of the regional cooperation we see today,” said Ammons, who worked with the committee that drafted the agreement.

Last month, Andress wrote a guest column, titled “How We’re Overcoming Distrust that Has Plagued Birmingham,” for David Sher’s ComebackTown blog (comebacktown.com), which is also published on AL.com. In the piece, she wrote, “Lack of trust and lack of working relationships hinder economic development and regional success. Many of our local political leaders didn’t know or trust one another, and they certainly didn’t work together.

“But this began to change dramatically when the Jefferson County mayors agreed to not pilfer businesses from one other and to work together on projects to help each municipality and improve our region. And we’re reaping stunning rewards as our municipalities, Jefferson County, state legislators, and business community work together for our region.”

Woodfin eagerly signed the Good Neighbor Pledge because it made sense for him and his counterparts, he said.

“We [started] working together. We had to,” Woodfin said. “What we agree to [with the pledge] is to communicate mayor-to-mayor, to say, ‘Listen, if somebody wants to move their employee group from Hoover to Birmingham voluntarily, let’s at least give notice. Let’s talk about what we’re going to do and support or not support. But we’re not going to steal jobs from each other because there’s no net gain.’”

Others who signed the pledge along with Woodfin include the mayors of Hoover, Bessemer, Center Point, Homewood, Mountain Brook, Trussville, and Vestavia Hills.

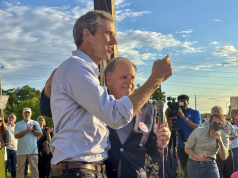

On February 11, mayors Woodfin and Brocato gathered with a small group of influential local leaders in downtown Birmingham for a photo shoot at Linn Park. Among those present were Waggoner, Stephens, Coleman, and Florie, as well as Alabama State Rep. Juandalynn Givan and Birmingham businessman Jesse J. Lewis, founder of The Birmingham Times. Many of these individuals have worked together for years.

“It’s all about cellphones,” Stephens said. “We all have [each other’s] personal cellphone numbers, and it works if you just pick up the cellphone and call—no egos, no audiences. Each person is results-oriented, and no one is looking for credit. We’re all looking for the same end result—to improve the quality of life for citizens [in the Birmingham metro area].”