By Rebecca Griesbach | rgriesbach@al.com

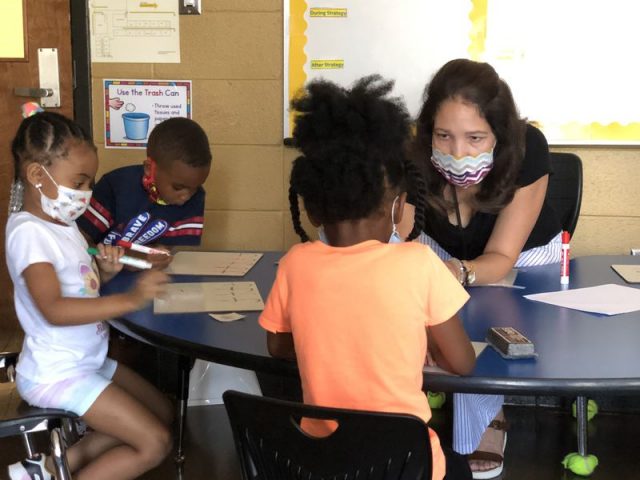

Every other Saturday, Principal Janice Drake drives to Birmingham’s Brown Elementary School to help teachers catch students up on reading and math.

“We just can’t get enough intervention,” she said recently, as two new tutors sat beside her, poring over bright red and green packets that listed the students they’d be coaching for the spring semester.

The tutors, one a freshman at Lawson State Community College and another a junior nursing student at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, are part of a multi-million dollar effort to curb learning loss in the district.

This month, more than 100 tutors from six area colleges began providing individualized math and reading instruction for small groups of students in every school in the system. They will be paid $15 an hour.

In 2020 and 2021, schools across the nation received an unprecedented amount of federal funding meant to help them recover from the pandemic. In Birmingham, the district is putting $29.5 million toward extra instruction, including after-school care, intersession periods and a recent partnership with area colleges to provide one-on-one tutoring.

When the pandemic shuttered schools for the first time in the spring of 2020, one in four Birmingham students didn’t have access to devices or internet at home, so the district sent them home with paper homework packets. That meant that for at least two months, it was nearly impossible to evaluate learning in the first couple of months of the pandemic, Superintendent Mark Sullivan said. And despite the work teachers put into online instruction in the following school year, the system struggled to get students back on track, he said.

Pandemic complications and changing assessments have made the past two years of student achievement difficult to measure. But officials say Birmingham City Schools saw an “enormous loss” in reading math scores from 2019 to 2021.

“We didn’t have the type of infrastructure in place to provide meaningful instruction to students beyond coming to school every day,” Sullivan told the room of tutors Monday. “… Virtual learning works for some students. But I will tell you, the vast majority of students do not learn in a virtual environment.”

At Brown Elementary, less than one percent of Drake’s students were proficient in math, and just 13 percent were proficient in reading, according to recent state data. Most of the students who are struggling, she said, are third-graders.

“If you can’t read, you can’t do math,” she said, noting that the school plans to adapt new statewide literacy guidelines to math instruction this year.

The tutors, Drake said, will allow regular classroom teachers to focus more of their attention on the whole class. She’s also hopeful that the tutors can be that constant reminder that college is possible.

“Younger students talking to young people about the importance of education,” she told them, is going to make all the difference. “You can sit down and explain things to them in a different way.”

Will it work?

Birmingham’s partnership is the latest among several efforts across the state to increase free tutoring services for Alabama students.

Houston County, for example, allotted some COVID-19 relief money for instructional aides, who tutor students after school and throughout the day. Other districts, like Bessemer City Schools, pay external companies for tutoring services. And in Jefferson County this fall, leaders hired additional math and reading coaches and implemented an after-school tutoring program that’s open to all students three days a week.

The state also required schools to hold summer reading camps in 2021. At Brown, teachers offered intensive reading instruction to about 70 children.

Drake said she’s seen success in other efforts to provide out-of-school instruction and expects to see similar results from tutoring. Nearly 100 of her students, she said, showed up to intersession in the fall – an effort by the district to provide additional instruction during seasonal breaks.

Experts say high-dosage tutoring is one of the most effective and versatile forms of interventions, but students need at least 50 hours of individualized coaching to see real gains. Careful data collection and high-quality materials can also make all the difference in a student’s learning, even when instructors aren’t certified.

In Birmingham, it’s up to tutors and schools to decide how often they will work. Sullivan said he expects tutors to work at least 15 hours a week at their designated schools. United Way of Central Alabama, which is helping to lead the effort, also is providing some training, and the tutors will use the same materials used in summer literacy camps, along with MathNation to coach students. Tutors will also log student progress in iReady, which is already used by the district.

Leaders say the partnership is an innovative way to not only provide extra instruction, but to get more future teachers in the pipeline and provide critical mentoring for area students.

“This is a step for me in my own career,” tutor Tashara Cooper told Drake at the meet and greet this month.

Cooper, a freshman at Lawson State, is majoring in general studies, but she’s thinking about pursuing a degree in elementary education.

“Why not teach kids?” she said. “They’re the future. If they can’t read and do math, then where are we gonna be? In the Stone Ages?”

AL.com’s Education Lab team is supported by individual donors and grants. Learn more about our work and sign up for our newsletter.