www.diverseeducation.com

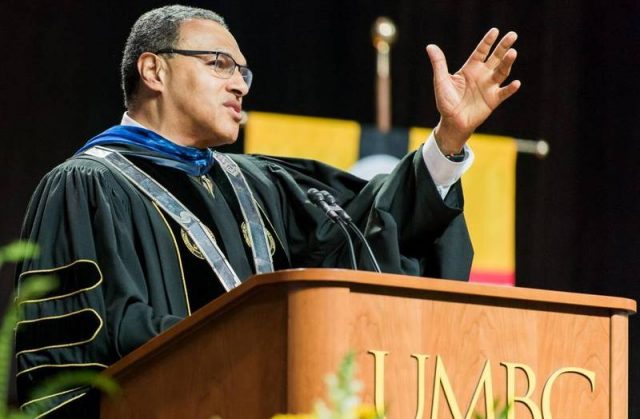

Dr. Freeman Hrabowski III, president of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, recalls a day he spent with renowned historian, author and civil rights activist the late Dr. John Hope Franklin more than a decade ago as one of the most memorable days in his life.

Franklin, of Birmingham’s Titusville community, had invited him to his home and to the Duke University campus, where Franklin was a professor emeritus, but Hrabowski didn’t realize until he arrived just how enjoyable the visit would be.

“He had an amazing facility that he and his wife had built just for orchids — the most delicate and rare of orchids — in his backyard. It was magical, just magical,” Hrabowski reflects, noting that, as they walked, the historian “shared his wisdom about life and about my work. He wanted to have conversations with me about the work that we do here at UMBC.”

After being notified he would be this year’s recipient of the Dr. John Hope Franklin Award, Hrabowski touched on some of the highlights of his career, but he also seized the opportunity to pay homage to the man he viewed as a mentor.

In a Zoom interview with Diverse, he says Franklin’s main message to him was that Hrabowski’s focus on diversity in the sciences was linked to Franklin’s work as the country’s leading Black historian.

“His point was that you cannot separate the production of Black scientists from the history of our country and our race,” Hrabowski says, adding, “It was that intersection that was critical.”

Hrabowski understood that intersection throughout his career and was able to put it into action when he partnered with philanthropist Robert Meyerhoff to found the Meyerhoff Scholars Program in 1988 to increase diversity in STEM-related fields by producing high-caliber Black and Brown graduates in those fields. The program has been so successful, producing 1,400 Meyerhoff Scholars with STEM degrees, that the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Pennsylvania State University, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and others are reproducing it.

“When we bring the Meyerhoff [scholars] to campus in the summer, they take courses not only in the sciences but in African American culture,” Hrabowski explains, adding that initially the curriculum was met with skepticism from some donors. “National agencies were not willing to fund the cultural part. They said, ‘What does that have to do with the production of scientists?’ But I said, ‘If you’re going to produce a broadly educated person in science, that person must know her or his history and sociocultural factors.’”

Among the Meyerhoff Scholars with STEM degrees, Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, an assistant professor of immunology and infectious diseases at Harvard University and one of the developers of the COVID-19 vaccine, is one of many standouts. According to National Science Foundation data, UMBC is now the nation’s top producer of Black graduates who go on to receive a Ph.D. in the natural sciences and engineering, an achievement that Hrabowski would like to see emulated by other institutions.

It is a fitting honor to both men that Hrabowski, who last summer announced that he will retire after the 2021-22 academic year, is the recipient of this year’s Dr. John Hope Franklin Award, presented annually by Diverse since 2004 in recognition of Franklin’s contributions to academia and the nation with his award-winning accounts of the African American experience, particularly in his iconic book From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans.

“I think of John Hope Franklin as a beacon of light for this country, a scholar who not only commanded the respect of historians but reached out to the larger American society . . . to make sure that we reflected on the significance of our history as a country and the challenges that African Americans have faced but also the strengths of the race,” says Hrabowski, whose most recent book is The Empowered University: Shared Leadership, Culture Change, and Academic Success.

Well-Deserved Accolades

Hrabowski, who received the award in a virtual ceremony on Nov. 16, is one of the nation’s longest-serving university presidents. He began his tenure at UMBC as vice provost in 1987 and became the university’s president in 1992. Before his tenure at UMBC, he served as dean and provost at nearby Coppin State University, an historically Black college.

His accomplishments have been recognized by numerous media outlets, including CBS’ 60 Minutes and by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, which in 2011 presented him with its Academic Leadership Award, one of the highest honors given to an educator. The award included a $500,000 grant, which he has directed to support innovation, entrepreneurship and student success at UMBC.

Hrabowski has seen the university’s enrollment rise from 10,000 to its 2020 level of 13,497 and transition from a primarily commuter school to currently housing over 37 percent of its student body on campus. He says that over the last 20 years the graduation rate has gone from 35 percent to 70 percent. Student newspapers can be highly critical of administrators, but UMBC’s The Retriever described him in glowing terms when he announced his retirement.

“Hrabowski is as synonymous with UMBC as the University’s Chesapeake Bay Retriever mascot,” the online paper stated. “Across campus, one can find students with pins of Hrabowski’s face attached to their backpacks.”

In a joint statement, University System of Maryland Chancellor Jay A. Perman and USM Board Chair Linda Gooden praised Hrabowski’s presidency, asserting, “It’s impossible to overstate his influence on UMBC and on its students, faculty, staff, and alumni . . . Dr. Hrabowski has led the university to national and international acclaim.”

Hrabowski chaired the National Academies’ committee that produced a landmark 2011 report on expanding underrepresented minority participation in STEM. The following year Barack Obama appointed him to chair the President’s Advisory Commission on Educational Excellence for African Americans. Shortly after that appointment, a popular TED talk of his, “Four Pillars of College Success in Science,” garnered more than a million views.

“Continue To Do Better”

As a graduate of an HBCU, Hampton Institute (now University), a former HBCU administrator and a member of a family of HBCU graduates, Hrabowski says he and his wife Jackie “are very proud of HBCUs, and we are supporters of HBCUs.” However, he has chosen to remain at a non-HBCU because he believes they are also critical to the education of African Americans. He points out that “more than 70% of Blacks are attending non-HBCUs and those institutions must do a better job in educating African American students.” Hrabowski is particularly focused on “the need to have people of color in positions at every level at institutions that are not HBCUs” and to increase the numbers of African Americans in the professoriate.

Hrabowski grew up in segregated Birmingham, Alabama, and was arrested in the 1963 Children’s Crusade. His emphasis on educational opportunity developed from his own background as a high achieving student who had parents, teachers and mentors guiding him toward excellence amid inequality. After graduating from Hampton with highest honors in mathematics, he earned his master’s in mathematics and a Ph.D. in higher education administration/statistics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Concerned about the numbers of undergraduates who initially major in science and engineering but do not earn degrees in those subjects, he tells Diverse, “We have a culture that does not support students to continue in those disciplines. We can all do a much better job of supporting our students in their first two years of science and engineering.”

It is that kind of support that Hrabowski believes has resulted in UMBC’s success in graduating African American and other students in STEM. Just recently, NASA awarded $72 million to UMBC and neighboring Morgan State University, an HBCU, to fund the new Goddard Earth Sciences Technology and Research II center known as GESTAR II. The project will create undergraduate and graduate research opportunities mentored by NASA scientists and engineers.

He is quick to note, however, that “as well as we are doing at UMBC, we know we can improve, we can continue to do better. I’m arguing that we can work on changing the culture at all of our institutions, to focus on high expectations not just for the students but for all of us. If large numbers of our students are not succeeding across disciplines, we should feel a responsibility. If we admit the students, we have a responsibility to help them succeed.”

This article originally appeared in the November 25, 2021 edition of Diverse. Read it here.