By Haley Wilson

The Birmingham Times

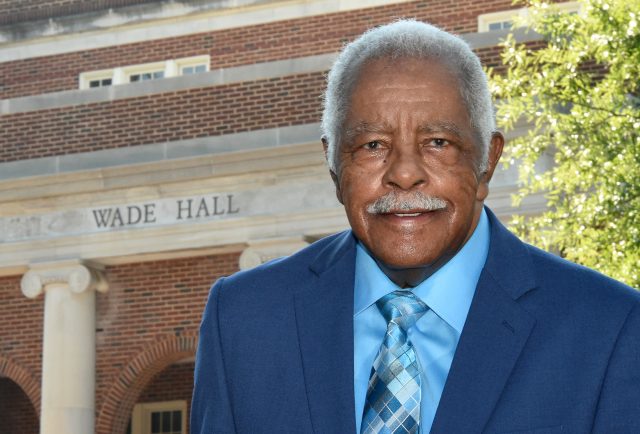

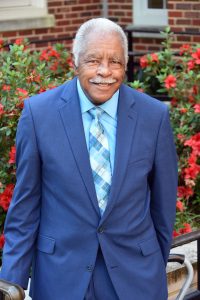

Due to his love of sports, Archie Wade, Ed.D., retired University of Alabama (UA) professor, is often referred to as the “Jackie Robinson” of the sprawling Tuscaloosa, Alabama, campus. For Wade, the nickname has a deeper meaning: “Breaking down barriers just like the sports legend,” he said.

Wade, the institution’s first Black faculty member in 1970, recently was awarded one of the highest honors bestowed on a college campus when the UA renamed one of its buildings in his honor—Moore Hall, which houses the department of kinesiology, is now “Archie Wade Hall,” following a vote from the UA System Board of Trustees in September.

“I was really emotionally ecstatic to know that something like this is happening. After all the challenges and things I’ve grown through, to finally get to this point is something I never thought I would have seen in my lifetime,” Wade told The Birmingham Times in an interview.

Wade recalled his early UA years as a “lonely period.”

“You go to meetings, and you’re the only Black person among 100 to 400 people from the college of education,” he said. “It’s kind of lonesome to look around and [see that] no one else [in the room] looks like me.”

He also remembered some upsetting walks through hallways.

“People would see me and purposefully walk the other way or walk as far away from me as possible,” he said. “[It was] like they didn’t acknowledge me as a person. Oftentimes, that really hurt.”

What kept Wade going during those “lonely” times was his faith.

“I just [told myself], ‘I’ll pray every day, and I’ll get through it.’ The Lord hadn’t failed me yet, and I didn’t expect him to then,” he said.

Wade said two people were instrumental in getting him to UA: then school President F. David Matthews, Ph.D. and Joffre Whisenton, Ph.D., who in 1968 was the first African American man to receive a doctorate from the institution.

In February 1970, Matthews, offered Wade a position as a professor in the Department of Kinesiology (then the Department of Health and Physical Education) upon a recommendation from Whisenton.

Wade, who attended high school and college in Tuscaloosa, was living in Louisville, Kentucky, at the time and was homesick.

“When I first got the call to come down, I was happy to receive it because it was a chance for me to [return] home to Tuscaloosa and be close to my parents and my brothers, who were still in school,” he said. “I was glad to accept the invitation.”

“Survival”

Wade was no stranger to history on the UA campus. He was one of three Black men who endured attacks from whites when they went to a football game in 1964, an encounter that would eventually lead to integration of the stands for spectators—more than a year after the successful desegregation of the campus in June 1963 by its first Black students, Vivian Malone and James Hood.

According to a TuscaloosaNews.com report, Wade said it was a love of football, not an aspiration to be trailblazers, that led him, long-time friend Whisenton, and Nathaniel Howard to take seats near midfield at the UA’s George Hutcheson Denny Stadium (later named Bryant-Denny Stadium) on Sept. 19, 1964, to watch the Crimson Tide defeat the University of Georgia.

“I wanted to see the game and watch [then UA quarterback Joe Namath] play,” Wade told the Tuscaloosa News.

Wade expected derogatory comments from some of the white fans, and it was a likelihood he was prepared to deal with. The anticipation was part of Wade’s matter-of-fact process of preparing for facing challenges.

“I can handle it. I was expecting it,” he said, adding that he expected heckles but not violence. “Though I wanted to go, I had the feeling that something might happen. Sometimes you just get a gut feeling about things, and I had one of those that day.”

Things were fine at the beginning of the game. The three young men sitting near the band in the packed stands were difficult to single out, Wade speculated: “When the band took the field, that’s when things got out of hand. I hate to say this. We were sitting ducks. People soon began throwing things at us, like ice [from their] cups.”

Wade and his companions decided that they would rather leave then be subjected to the animosity of the crowd, so they left during the second half before things could get worse.

“In the Black community, it was called survival,” Wade said of the decision. “We approached security about being escorted out, but the guard declined to help. …

As we were walking, more objects just kept coming at us. … It could have been a lot worse, and I think it would have been a lot worse if we had stayed. I was just thankful to God that nothing happened to us.”

Wade’s return to the campus six years later was much different.

“I had a pleasant visit with the vice president and the dean of the college department and went back to Louisville,” he said. “Eventually, I got a call telling me that I been hired If I wanted the job. I called my dad, returned to Tuscaloosa, and started [at the UA] on Feb. 1, 1970.”

Early Years

Wade, born in 1939, lived in Madison County, Alabama, for the first 14 years of his life before his family relocated to Tuscaloosa. “My family moved to Tuscaloosa in 1953, and then I came down in 1954,” he said.

That same year, Wade started his 10th grade year at Industrial City High School, now Druid High School, which was segregated.

“When I started school, I had to catch a school [bus] because we didn’t have a school in our community. We had to go to the next community,” he said. “They had a school for whites in [the community we moved to]. … I could see the school from where I was catching the bus, but I couldn’t attend [due to segregation]. We rode about seven or eight miles to make the rounds to get to school in the next community.”

Even though he and his community members were separated, Wade says he still felt connected.

“We had plenty of white friends that we played basketball with every afternoon after school,” he said. “We could do things like play after school, but we just couldn’t go to school together.”

After graduating from high school in 1957, Wade was awarded an athletic scholarship for baseball from Stillman College, a historically Black college and university (HBCU) in Tuscaloosa, where he pursued a degree in business.

“I was offered an athletic scholarship, and that was my main reason for going because I was living in the city and my room and board would have been paid for,” he said.

As a student, Wade became certified to teach physical education and organized local baseball and basketball leagues at the YMCA on Tuscaloosa’s West Side. In 2010, he was inducted into the YMCA’s Hall of Fame.

“I had a part time job at the Y,” he said. “I worked the whole time I was in school. I took classes during the day, had baseball practice and basketball practice in the afternoon, and worked at night. … It was not easy.”

Wade overcame those challenges and graduated from Stillman in 1962, and his former mentor and coach, Whisenton, helped him get hired at Stillman. Wade spent eight years in the school’s Physical Education Department, coaching baseball and basketball.

Whisenton had a profound personal and professional influence on Wade: “He was the head baseball and basketball coach, and I was an assistant to him. He was my coach in college, and then I had the opportunity to work with him. … Through those experiences, we were able to build our friendship.”

In addition to working at Stillman, Wade played minor league baseball with the St. Louis Cardinals organization from 1964 to 1967. He had been discovered by a scout who would often come to Tuscaloosa to watch football players, and he was permitted time off by the Stillman administration to play during the summer.

As he traveled with the Cardinals, Wade was often reminded of race. Sometimes he would be the only Black person with the group, other times there would be as many as three. One time, a restaurant in Florida refused to serve Wade, prompting the team manager to take the players elsewhere.

“That was the time period I lived in,” he said. “Unfortunately, it was full of hatred, but that wasn’t always the case everywhere I went.”

The Bear

While holding down his Stillman faculty job, Wade worked as a recruiter with legendary UA football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant.

“I had a chance to work with Bryant and some of the assistant coaches,” he said. “I know they wanted me to do it because I was Black, and they were trying to [recruit] Black players. … They would ask me to go out on Fridays, watch the players during games, and take the athletes’ families out to dinner.

“On Saturdays, we would take [the players and their families] to dinner again, and they would often ask me what I thought about the players, if they would be a good fit, and things like that. It was like a report I did. If they were serious about coming [to the UA], the [players] would stop by my office, and I would share my experience honestly.”

Wade helped with recruiting for two years, after which, “I told coach Bryant that I enjoyed it, … but it was time for me to get away from that.”

Wade, who has been married for 60 years and has five children and nine grandchildren, would go on to dedicate more than 30 years to teaching before retiring in 2000. In 2013, he was honored during the UA’s “Through the Doors” activities, which commemorated the 50th anniversary of integration at the university. For his contributions to the campus, Wade was presented a plaque—and it is currently on display in a conference room in Archie Wade Hall.

“Overall, my time at the university was good,” he said. “You’re gonna have ups and downs. You’re gonna have peaks and valleys. You’re gonna have periods where you go through things. I think the important thing is how you deal with it. … I had some wonderful friends, [and] the faculty was great. I can’t speak for everyone, but I enjoyed my time.”

Updated at 12:04 a.m. on 10/23/2021 to include information about Dr. Wade’s family.