By Bob Blalock

Alabama NewsCenter

University of Alabama coach Nick Saban completed a decade of dominance in college football this past January when his Crimson Tide team demolished Ohio State 52-24 for the College Football Playoff National Championship. The victory brought Saban and Alabama a fifth championship in 10 years (2011, 2012, 2015, 2017 and 2020), an unprecedented run of excellence.

That is, unless you know about Tuskegee Institute (now University) nine decades earlier, when the Golden Tigers won six national titles in seven years. Coached by Cleveland Leigh “Cleve” Abbott, Tuskegee claimed Black college football championships from 1924-27 and in 1929 and 1930. During those six championship seasons, his teams won 57 games, with no losses and four ties. From 1924-33, the Golden Tigers swept 10 straight Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (SIAC) titles.

Saban no doubt can appreciate that kind of domination.

Abbott is a fascinating figure whose impact extended far beyond Tuskegee and college football, using his role as the athletic director of a small, historically Black college as a platform for social change during the Jim Crow era of segregation.

His father, Elbert B. Abbott, was born into slavery in 1862. Elbert married Mollie Brown in 1890 and the two left Alabama for South Dakota, where Cleve Abbott was born Dec. 19, 1894 in Yankton. Abbott’s parents moved to Watertown, where he became a star athlete at Watertown High School, earning 16 letters in four sports.

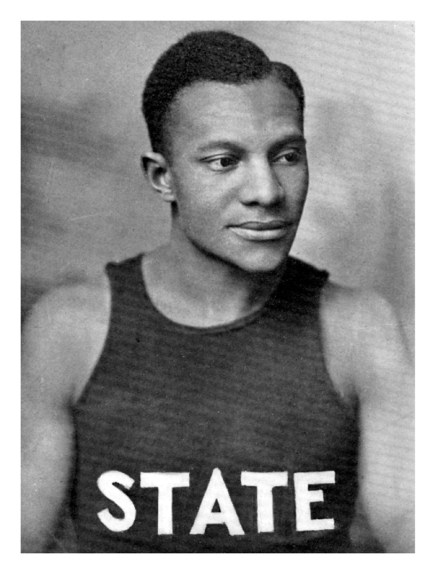

Abbott was a student at South Dakota State College (now University) when Tuskegee Institute founder and President Booker T. Washington recruited him “to quietly lead an effort to help break American Jim Crow segregation through sports,” said business consultant and activist Bruce Danielson in his speech for Abbott’s induction into the South Dakota Hall of Fame in 2018.

Creating Possibilities

“This child, brought up with the South Dakota idea he could do anything, would find ways to create possibilities for young men and women not allowed to dream,” Danielson said. “Likely shocking his parents, this oldest child of the former slave would return to their Alabama roots to help break American segregation.”

That Washington even found out about Abbott was happenstance. The Daily Plainsman in Huron, South Dakota, on June 5, 1955 detailed the chance encounter between Washington and South Dakota State President Ellwood C. Perisho. The story, a remembrance of Abbott published two months after he died in Tuskegee, said Perisho had attended “a meeting for the advancement of the colored race” in New York City in February 1913.

After the conference ended, Perisho was leaving New York by train “when a tall, nicely dressed colored gentleman sat down opposite him and introduced himself as Booker Taliferro Washington, the president of Tuskegee Institute.”

The two talked, and Washington told Perisho he wanted to start a sports program at Tuskegee and asked if Perisho knew of someone who could direct the program. Perisho told him about Abbott, who was just a freshman at the time.

“You go back to tell this young man, if he will be a good boy and study hard, he can be my sports director when he graduates from college,” Washington told him.

Washington died in 1915 before Abbott graduated with a degree in dairy science, but Washington’s secretary found a memo of agreement for Abbott’s employment and sent him a contract.

Fresh out of college in 1916, Abbott moved to Tuskegee to be a coach and agricultural instructor.

World War I exploded those plans. Abbott joined the Army in 1917, serving with distinction as a first lieutenant in the all-Black 366th Infantry Regiment in the 92nd Division. As a regimental intelligence officer, he saw battle at the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in France in 1918, the deadliest campaign in American history with more than 26,000 U.S. soldiers killed in action, according to the National Archives.

Returning To Tuskegee

Abbott joined the faculty of Kansas Vocational School in Topeka after the war. He coached and was commandant of cadets, but in 1923 he returned to Tuskegee as the school’s athletic director and football coach. He held both those positions, as well as many others, until his death in 1955.

Abbott didn’t take long to establish excellence in football, winning his first championship in his second year as coach. Player Ben Stevenson had a little something to do with that. Abbott had discovered Stevenson working on a farm in Liberty, Kansas, and recruited him to Tuskegee.

Stevenson was blessed with great size and speed, and was famous for his long runs – Tuskegee credits him with 42 touchdown runs of more than 50 yards. He also intercepted 39 passes in his career and was a noted drop kicker. From 1923-1930, he led the SIAC in rushing, scoring, kicking and interceptions.

Stevenson was a Black College All-American a record-setting seven times from 1924-30. He played his first four years enrolled in Tuskegee Normal & Industrial Institute High School and was allowed to take part in college athletics. Then, he played four more years as a collegian.

How dominant was Stevenson? The College Football Hall of Fame put it this way: “In the 1920s Golden Age of Sports, ‘Big Ben’ was to Black college football what Babe Ruth was to baseball or Red Grange was to the rest of college football.”

In the 81 games Stevenson played, Tuskegee lost just two, with nine ties and 70 wins.

Abbott would never match that level of success for the rest of his coaching career, but he is still Tuskegee’s all-time leader in wins with 202 across three decades.

Abbott’s greatest accomplishment in athletics, though, came with the women’s track team.

In 1927, Abbott, who coached the men’s track team, created the Tuskegee Relays “to counter the dearth of available rivals and other negative effects of Jim Crow on student athletes,” wrote historian Anne Blaschke in “Southern Cinderpaths: Tuskegee Institute, Olympic Track and Field, and Regional Social Politics, 1916-1955.”

By 1929, female students who had seen the success of the Tuskegee Relays for the men’s track team “voted heartily in favor” of starting a women’s track team after the original one had withered, according to Blaschke, a lecturer at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Abbott added two women’s events to the 1929 Relays and the Tigerettes were quite literally off and running.

Planning For The Olympics

“Coach Abbott was ambitious. Within one year of including women in the Tuskegee Relay Carnival, he announced plans to mold his green young runners into Olympians,” Blaschke wrote. “With expectations that his women would attain elite status in the United States, Abbott developed a comprehensive training regimen to build the program’s strength from the ground up.”

The Tigerettes won individual and team awards at the Tuskegee Relays and just a few years into their existence were claiming conference championships. By the mid-1930s, they ruled U.S. track. Starting in 1937, the women’s team won the national senior championships of the U.S. Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) an astounding 14 times in 15 years, according to “A History of Sports at Tuskegee,” an unpublished manuscript by former Tuskegee coach Ross C. Owen.

Despite the massive success, Abbott’s goal to create Olympians at Tuskegee went unfulfilled through the 1930s into the late 1940s. The International Olympic Committee canceled the 1940 and 1944 games because of World War II, which limited Tuskegee’s athletes to domestic competition that they dominated.

“The Tigerettes succeeded against Southern racism by exercising (Booker T.) Washington’s long-held mentality of friendly relations with the white community and underlying determination to produce elite students,” Blaschke wrote.

That success came even as Jim Crow shadowed the teams as they traveled to national meets. Abbott and his wife, Jessie, worked hard to make the road trips as homelike as they could, Blaschke wrote, with food bought at grocery stores turned into roadside picnic lunches and warm dinners that Jessie Abbott heated on the hot radiator of a car. Those meal times became collective team-building moments while the athletes spent nights “in private negro homes.” Still, Jim Crow ensured that bathroom stops meant “hitting the fields” instead of public restroom use.

Meanwhile, Abbott’s influence was growing across the South and nationally. In 1946, he accepted a position on the U.S. Olympic Committee Track and Field Games Committee for the 1948 Olympics in London, becoming the only Black USOC member. One of his proteges, Alice Coachman, won the high jump there, becoming the first Black woman to claim an Olympic gold medal.

Coachman was born into crushing poverty in Albany, Georgia. Barred from white sports facilities as a girl, she created high jumps from string, sticks and rags, according to a 2004 National Public Radio interview as part of the “National Visionary Leadership Project” (NVLP), which Blaschke cited in her work.

Coachman went with her local high school to the Tuskegee Relays and smashed the high jump record. But Abbott had a difficult time convincing Coachman to train at Tuskegee, at least partly because she was so poor – she actually jumped without shoes until teachers bought her some, Blaschke wrote. Tuskegee was a much more worldly and intimidating place for Coachman than Albany.

“The thing that sold me,” Coachman said in the NVLP interview, “was that in the summer of 1939, they had the World’s Fair in New York City … and the whole team went to the World’s Fair.”

During her years competing in high school and college at the Tuskegee Relays, Coachman won the high jump every year (1939-46), won the 50-meter run twice, the 100-meter dash three times and was on the winning 400-meter relay team four times. At the national AAU competition, she won the high jump each year from 1941-48, the 50-meter run six times, the 100-meter dash three times and was a member of the 400-meter relay champions three times, according to Tuskegee’s Owen.

After Coachman’s Olympic victory, Abbott was asked to serve on the Women’s Track and Field AAU Selection Committee – the same group, Blaschke noted, that less than 15 years earlier had barred Black runners from competing.

Abbott coached five other women at Tuskegee who competed in the Olympics. Mildred McDaniel won a gold medal in the high jump in the 1956 Olympics, while Nell Jackson, Theresa Manuel and Mabel Walker were members of the 1948 U.S. team and Mary McNabb was a member of the 1952 U.S. team. Another track star for Abbott at Tuskegee was Evelyn Lawler, the mother of nine-time gold medal winner Carl Lewis.

For good measure, Abbott also led the Tuskegee men’s basketball team to an SIAC championship in 1934, as well as coached baseball, golf and tennis, producing several men’s and women’s American Tennis Association national champions.

Despite his amazing coaching success, Abbott’s legacy transcends all the championships and All-American athletes and Olympic gold medals.

Changing The World

“Cleveland Abbott inspired kids who had nothing to believe that they could change the world, just by their very dreams and actions,” Danielson said at Abbott’s South Dakota Hall of Fame induction. “He honors all of us through his excellence. In his short life, he was able to blend raw talent with a superb mind to break the rules of American segregation.

“The quiet excellence and dignity of Cleveland Abbott should teach all of us what one brave person can do to change the world.”

Among Cleveland Leigh “Cleve” Abbott’s other honors:

National Football Hall of Fame, 1948.

South Dakota Sports Hall of Fame, 1968.

South Dakota State University Hall of Fame, 1968.

Tuskegee University Hall of Fame, 1975.

Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference Hall of Fame, 1992.

Alabama Sports Hall of Fame, 1995.

USA Track and Field Hall of Fame, 1996.

Watertown Sports Hall of Fame, 2002.

American Football Coaches Association Trailblazer Award, 2005.

Black College Football Hall of Fame, Class of 2012.

In addition, the city of Tuskegee is home to the Cleveland Leigh Abbott U.S. Army Reserve Center, and the Tuskegee University Golden Tigers football team plays its home games at Cleve L. Abbott Memorial Alumni Stadium, which he helped build in 1924-25.

This story appeared originally on www.alabamanewscenter.com