By Mark Kelly

Alabama NewsCenter

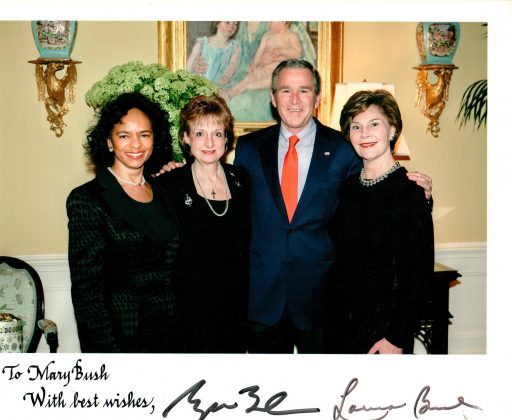

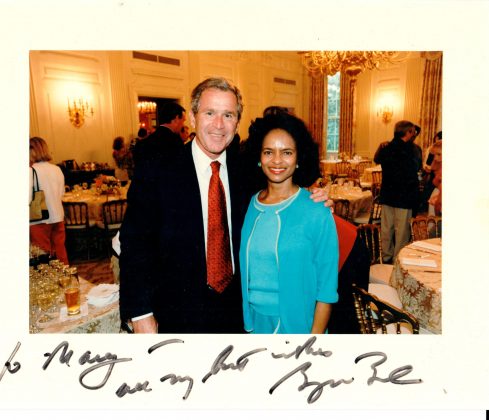

Mary Kate Bush‘s career is remarkable by any measure. She has worked for three U.S. presidents. She was among the first generational wave of Black women to accumulate influence on Wall Street and rise through the ranks of corporate America. She is an expert on global economics who continues to work as a high-level consultant, serve on numerous boards and mentor young people to prepare them for successes – and challenges – of their own.

It’s a compelling story for Bush, chairman & founder of Washington D.C.-based Bush International, LLC who serves on several public company boards: Bloom Energy; Discover Financial Services; ManTech International Corporation and T. Rowe Price Group, made even more so by the particulars of Bush’s biography.

Born in Birmingham at a time when the city was a known bastion of resistance to racial equality, Bush grew up in the “colored” neighborhood of Titusville and attended segregated schools. Far from feeling limited by her circumstances, Bush was encouraged practically from birth to work hard, to value learning and not just to set goals, but to achieve them.

“I was being taught lessons I didn’t always know I was learning,” Bush said. “One was to keep your eyes focused on where you want to go and what you are trying to accomplish. From the start, I was encouraged to focus on being the best I could be.”

The Power Of Home

That objective was instilled first by Bush’s parents, Johnny and Augusta Bennett Bush. The Bushes met and married in their native Uniontown, in Perry County, where both of their families had farmed cotton for three generations.

The young couple moved to Birmingham because Johnny Bush, like many other young men from Alabama’s Black Belt region, saw an opportunity to make a better living in a steel mill than in a cotton field. He was a laborer at U.S. Steel‘s Ensley Works, but also worked two other jobs as a janitor on weekday evenings at the U.S. Steel credit union office and Liberty National Insurance Company in downtown Ensley. On Friday nights, with no school the next day, Mary and her older brother sometimes accompanied their father to the office buildings to help with the work.

“I tell people I got my start in finance early,” Bush said laughing, recalling the time spent cleaning the empty credit union building. “But that is one of the ways my father taught us the value of hard work. He was doing what was necessary to give us a good, middle-class life in Titusville.”

Bush credits her mother with imparting the values of honesty and integrity, saying, “She loved the story of George Washington chopping down the cherry tree and saying, ‘I cannot tell a lie.’” But Augusta and Johnny Bush placed the highest value of all on education.

“My mother only went to school through the 10th grade, because the Black high school in Uniontown stopped there,” said Bush. “My father was the oldest boy in his family, and when his father died, he had to leave school and work the farm. But he had a keen intellect and a love of learning, and he educated himself by reading. Consequently, both of my parents were absolutely dedicated to the idea of education as the key to being one’s best.”

The lessons learned at home were reinforced throughout the surrounding community. Segregation notwithstanding, the Titusville of the 1950s and early ’60s was very much an aspirational middle-class neighborhood. Established doctors, lawyers, educators, store owners and other professionals were neighbors of wage earners like Johnny Bush, who strived to achieve and maintain for his family the benefits of middle-class status. Across whatever socio-economic lines existed within Titusville – and amid the burgeoning of the civil rights movement – the community was united in its determination to ensure a better future for the generation of children then coming up – Mary Bush’s generation.

“It was like having a neighborhood full of aunts and uncles. Our neighbors looked out for all of us kids – and they told our parents if we were doing anything untoward.” Bush said chuckling, adding, “That was a good thing, even if I didn’t always think so then.”

Encouraging Scholarship

The protective, nurturing cocoon of the community extended to its churches. Bush’s family attended Sixth Avenue Baptist Church, then in its original location at Sixth Avenue and 16th Street South. The church’s longtime pastor, the Rev. John T. Porter, always exhorted his congregation to “keep looking up” – a message that resonated with Bush and other young people. Porter organized field trips and expected to see the report card of each child in the congregation, so during the Sunday service he could recognize those who excelled academically.

Bush met another minister who played an influential role in her development when he knocked on her family’s door. The Rev. John Rice was there to invite the Bush children to join a youth fellowship group that met a few blocks away at his church, Westminster Presbyterian. Augusta Bush conferred with a few other mothers, and they allowed their children to attend Rice’s youth activities, which included chaperoned dances. It didn’t hurt that the minister was also the guidance counselor at Ullman High School.

“As Black kids, our options were limited, so it was a social outlet,” said Bush. “It also gave us another connection to the church. As both a minister and our guidance counselor, John Rice had a sixth sense about kids, about our issues and problems and thoughts. He was very wise.”

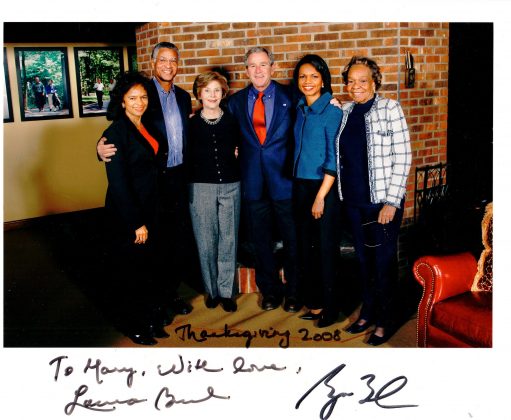

Rice’s fellowship group provided Bush with her first connection to his precocious – and, to older kids, occasionally annoying – daughter, Condoleezza. The two were separated by several years, so it wasn’t until 25 years later, when both were working in Washington, D.C., that they reconnected and became the close friends they remain today.

The network of encouragement and support Bush and her friends enjoyed was rounded out by school. She “loved school,” and has grateful memories of the teachers who had the greatest impact on her. At Ullman High, in addition to John Rice, those were math teacher Mabel Carey, French teacher Dannetta Thornton and history teacher Odessa Woolfolk – later the founding president and currently chair emerita of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute – along with Principal George Bell, “a dynamic individual, very much involved with the students.”

“There was no complacency,” Bush said. “It was always about encouraging scholarship and pushing us toward excellence. No matter the challenges you face, you can find a way to get done what you need to get done and keep moving forward.”

‘I Wonder What They’ve Bombed’

Keeping that attitude while meeting the routine challenges of childhood was complicated by the realities of life in segregated Birmingham. Blacks could not patronize the same restaurants or movie theaters as whites; they could not use the main Birmingham Public Library downtown; they could shop at “white” department stores but could not use the dressing rooms; Black children were allowed to hear Birmingham’s symphony orchestra play – one day a year.

As she matured, Bush came to realize how much her parents and the community network that surrounded her did to try and protect her from the worst of a time and place where the threat of violence against Blacks was constant. Outside of school, church and occasional trips downtown with one or both of her parents, her regular sphere of activity consisted of the area of Titusville around the Bush’s house on 17th Court South and, once she was in high school, jaunts to the adjacent Smithfield neighborhood to visit friends who lived there.

“Even as a kid, I was very aware of segregation, because there were places we couldn’t go,” Bush recalled. “As I grew up, my awareness became keener, and I understood how much my parents were protecting me.”

For Bush, the grimmest reality of segregation hit home with stunning force on Sept. 15, 1963. That Sunday morning, the Bush family was at home – for reasons soon forgotten, they were not attending church at Sixth Avenue Baptist that day – and 15-year-old Mary, who’d just begun her junior year at Ullman, was in the kitchen preparing her breakfast. She heard “a very loud noise” that she identified immediately.

“My first thought was, ‘I wonder what they’ve bombed now,’” said Bush, reflecting the frequency with which local segregationists perpetrated bombings of Black homes and businesses.

Radio news reports soon made it clear that the bombing of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church was different. The bomb detonated between the Sunday School and church hours, destroying a downstairs restroom, killing four young girls and severely injuring another. Two of the girls who died were friends of Bush’s: 14-year-old Cynthia Wesley – “she’d come to my 15th birthday party a few months before” – and the daughter of one of Bush’s teachers at Center Street Elementary School, 11-year-old Denise McNair, whom she recalled as “very bright, a little light in the world.”

“It was heartrending,” Bush remembered of receiving news of the girls’ deaths and the days that followed. “But we weren’t taught to hate.”

A Journey Begins

Bush graduated from Ullman High with honors in 1965. Colleges outside the South – including the “Seven Sisters” that were female counterparts to the then-mostly male Ivy League schools – were opening up admissions and actively recruiting Black applicants for the first time. Bush’s two closest friends, Sheryl McCarthy and Sandra Copeland, went to Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, and she was accepted at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania. But after having made a visit to Fisk University, in Nashville – the first historically Black college to earn a Phi Beta Kappa charter – her mind was made up.

“My father wanted me to go to Tuskegee because it was close to home,” Bush said. “But I had fallen in love with Fisk, and it was one of the best historically Black colleges in the country at the time, which was important to me. There was definitely a tug and pull, and Fisk was more expensive, but somehow my mother came over to my side, and I went to Fisk.”

After a youth spent in the “cocoon” of home, church and school in segregated Birmingham, Mary Bush was making her first move into the larger world. Her journey along the road of excellence and accomplishment for which she had been prepared was just beginning.