By Solomon Crenshaw Jr.

Alabama NewsCenter

For generations, football Saturdays have been silent on the campus of Talladega College.

No tailgating. No revelry. No pageantry. None of the excitement that permeates so many college campuses in the fall across Alabama where throngs of fans fill stadiums to cheer on their gridiron heroes.

But there was a time when Talladega College fielded one of the best football teams among Black colleges. And perhaps it will again, with a feasibility study under way to gauge whether football should return.

This year is the 100th anniversary of Talladega College winning back-to-back Black college football national championships in 1920 and 1921. Coached by Jubie Bragg, the team dominated the competition those years.

“The Talladega College Crimson Tornado football team was once an HBCU powerhouse football program,” said Acting President Lisa Long. “It had numerous good seasons and several star players.”

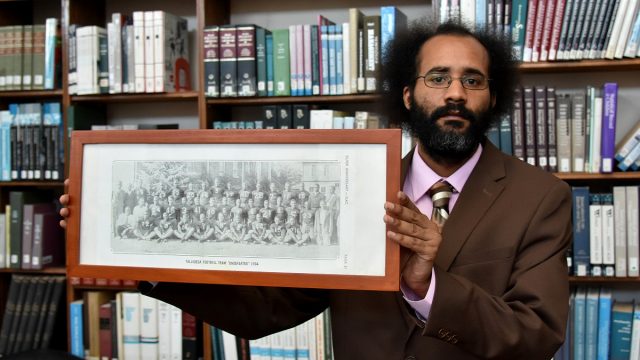

Allen McQueen, a programs and research librarian at Talladega College, echoed that sentiment.

“Talladega College was one of the perennial powerhouses in Black college football, which I think means it’s one of the premier powerhouses in all of football at the time,” he said. “They just weren’t given the opportunity to prove that with the predominantly white schools.

“They had several undefeated seasons, several seasons in which they never gave up a touchdown, in which the opponent never scored on them,” McQueen continued. “They won the first two Black college football national championships, in 1920 and 1921. Throughout the time of their existence as a football team, they were for the most part a powerhouse. Even when they weren’t one of the best teams, they were still having winning seasons. They were always consistently good and were one of the most-known Black college football teams in the country.”

The earliest reference to the team is a mention of it traveling to Tuskegee Institute to play a game in 1906. Talladega College was a founding member of the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference in 1913. The team remained in the conference until 1941.

The standout 1920 squad won five games and tied one, ending that campaign with a 28-0 win over previously unbeaten Tuskegee Institute.

A story from The Birmingham News said, “It was the good old American game of football with the ambulance kept near to waft away the victims. The championship for Talladega hung upon this game, and no wonder it had all the thrills of a ‘bull fight.’”

Records from the time acknowledge that as a historically Black college, Talladega was unable to play games against white colleges and competed with other historically Black colleges.

In 1920, the Pittsburgh Courier, an African American weekly newspaper, began selecting national champions from Black college football teams. The Courier selected Talladega and Howard as co-champions for the 1920 season. Another source in January 1921 rated Talladega, Howard and West Virginia Collegiate Institute as the top three “colored” football teams for the 1920 season.

The 1921 team was 6-0-1. The Birmingham News reported that Talladega’s quarterback, “Skeats” Gordon, was “reputed to have been showing dazzling ability all this year.”

Again, the Courier named Talladega co-champions of Black college football. The Tennessee Docs and Southwest Texas were 8-0 and 7-0, respectively, in 1921.

“President (Buell) Gallagher recommended in 1942 that Talladega College discontinue its football and basketball programs for the duration of World War II,” Long said. “Other HBCUs like LeMoyne-Owen and Fisk did the same.”

Since then, fans of college football among students and faculty at Talladega College have had to travel to other campuses to feed their need. In the spring of 2021, the groundwork was laid for a possible return of the sport.

In April, the Talladega College Board of Trustees authorized then Talladega College President Billy C. Hawkins to employ a consultant to determine the feasibility of reviving the football program.

“The year 2021 marks the 100-year anniversary of our historic back-to-back championship win,” said Hawkins, who recently stepped down for health reasons. “Given the success of our academic and athletic programs; the recent growth and transformation of the college; and the myriad benefits of having a football program, now may be the time to revive our team. This could be great for the college, the community and central Alabama. However, our decision will be based upon the findings of a formal feasibility study.”

Long said the study will not be completed until January. “There is no plan for football at this time,” she said.

But the prospect of football’s return has created a buzz on and around the campus.

“I’m sure that students will be excited about a new activity on campus,” the acting president said. “And the community would be involved if that were to happen.”

The athletic teams of Talladega College compete in the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) as part of the Southern States Conference. Some members of that conference field football teams, which play in the Mid-South Conference.

Long said she is not concerned that football might harm Talladega College.

“I don’t think that when the football team was in existence at Talladega that it changed the academic excellence that Talladega is known for,” she said. “I don’t see that happening. If the feasibility study deems that football is necessary and … we decide to move forward with that, I don’t see it changing what Talladega College has been.”

McQueen frequently travels to metro Birmingham to take in high school action on Friday nights. He and others have found little that commemorates the bygone era of football at Talladega College, except for a photo of the undefeated team of 1934. He’s found nothing about the back-to-back national champions.

“That hits me, as both a historian and as a football fan,” said McQueen, a native of Guam who was raised in Hermitage, Tennessee, outside Nashville. “It troubles me as a historian that any kind of history is not properly recorded and presented. Being that we’re a Black college, I think our history as Black people is important.

“And I think our institutional history is important,” McQueen continued. “On that level, I think we’re missing an opportunity by showing what we have been in the past and what we can be in the future. But as a sports fan, as a football fan, it does particularly bother me that there’s not more knowledge of the football team.”