By Michael Sznajderman

Alabama Newscenter

Walking through the grand auditorium and other spaces inside the long-closed Masonic Temple on Birmingham’s Fourth Avenue, it’s easy to picture the bustle of activity that once took place on every floor.

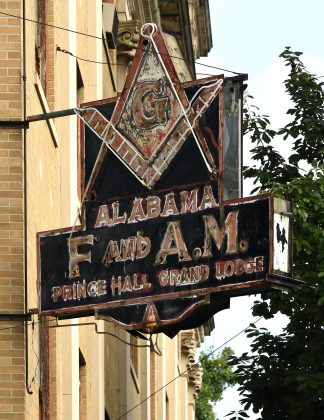

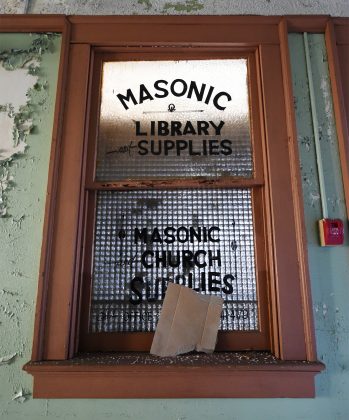

Built between 1922 and 1924 for the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge, Free & Accepted Masons of Alabama, the building was a hub for the Black community in Birmingham, housing retailers, professional offices, fraternal organizations, labor unions and the first public lending library open to Blacks in the city.

Trailblazing Black civil rights lawyer Arthur Shores had an office in the building, as did Black doctors, dentists and even talent scouts. It housed the state headquarters of the NAACP, which was padlocked in 1956 when a state judge banned the organization from operating in Alabama.

But it’s the auditorium, with its still-intact stage and balcony, marble columns and decorative plaster friezes that is perhaps the most evocative part of the temple. In this room that could accommodate 2,000 people, generations of Blacks from across the region gathered for proms, balls and dances, civic and social club meetings, and to hear the biggest Black entertainers of their day. Count Basie’s and Duke Ellington’s big bands were regular performers.

“This ballroom was a place for a lot of firsts in Birmingham,” said Llevelyn Rhone. Project manager with Historic District Developers, Rhone leads operations on the ground as plans come together to completely restore the building and more.

“This was not only a place for folks to meet but also a place for ideas to be shared, for entertainment and for some of those milestones unique to life,” he said. “It all happened in this building.”

In addition to restoring the building in a way that respects its historic character, long-term plans call for a residential tower on the property adjacent to the Masonic Temple – the first, significant residential development in the Fourth Avenue District in decades. Both projects are a joint initiative of Direct Invest Development and Henderson and Company, with support from the city of Birmingham and other organizations.

“The vision goes beyond the building and the collaborative work there with the Masons … to the Fourth Avenue area,” Rhone said, calling it “part of catalytic development here that will bring people who will actually live in the area … bringing life, 24-hour life, back to this area of town.”

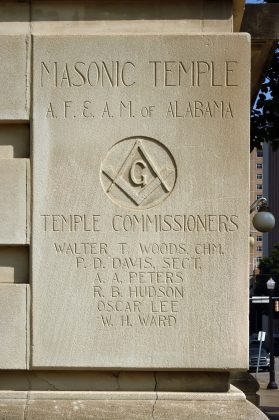

There’s much more history behind the Masonic Temple, Rhone said, starting with Robert R. Taylor and Louis H. Persley, who designed the seven-story, Renaissance-revival structure. Taylor was the nation’s first accredited Black architect and the first Black to graduate from MIT. He also designed many of the buildings at Tuskegee Institute, now Tuskegee University, along with several Carnegie libraries. Persley, a graduate of Lincoln University and Carnegie Institute of Technology, now Carnegie Mellon University, also designed several structures on the Tuskegee campus.

In October 1932, the Communist Party-affiliated International Labor Defense held a civil rights conference in the Masonic Temple auditorium. It was a response to the infamous Scottsboro Boys trial, in which nine innocent Black teens were accused of rape. The gathering was one of the first major civil rights events in Birmingham, setting the stage for future civil rights actions in the city.

Indeed, because of its historical importance, the building is one of the structures included in the footprint of the still-developing Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument.

“We’re very much committed to bringing life back to these walls, so they can tell yet the next chapter of the people of Birmingham and their stories,” Rhone said.

The story appeared originally on the Alabama Newscenter website.

To read related stories, click one of the links below.

Restored A.G. Gaston Motel at Heart of Civil Rights National Monument