By Michael Sznajderman

Alabama Newscenter

In her police mugshot taken 60 years ago in Jackson, Mississippi, Catherine Burks-Brooks looks straight into the camera, without fear or agitation. One might even interpret the curve of her mouth as a smirk.

What was Brooks – then a 21-year-old college student and Freedom Rider, already battle-hardened from several civil rights actions – really thinking about when the bulb flashed?

“When they took that picture, I knew I was going to jail,” said Brooks, who lives in Center Point, near Birmingham. “I was tired. I was hungry. And I was ready to get into bed. I was not afraid.”

Her greatest concern, she recalled, was grabbing a top bunk in the cell, so she wouldn’t be forced to sleep on the cold, hard floor.

Burks-Brooks spent weeks behind bars in Mississippi, first in a county jail and then at the infamous Mississippi State Penitentiary – “one room over from the electric chair” she remembers. Her crime: peaceably challenging the South’s segregated interstate buses and bus stations.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the Freedom Rides, which broke the back of race-divided interstate transportation in the South. From May to September 1961, more than 60 Freedom Rides took place, during which more than 400 young Blacks and whites traveled shoulder-to-shoulder, challenging the Jim Crow transportation laws that a Supreme Court ruling had struck down but that cities across the South were ignoring.

After months of nonviolent civil disobedience by the Riders, hundreds of arrests, and several ugly and violent attacks by those opposing them, the racist system finally fell after the federal Interstate Commerce Commission officially outlawed segregation on interstate mass transit.

Last month at the Birmingham Public Library, Burks-Brooks appeared in front of a vintage Greyhound bus dating from the early 1960s – one similar to those boarded by the Freedom Riders. The bus, recently refurbished by the Alabama Historical Commission, has been traveling the state to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Freedom Rides. Birmingham was the last stop for the bus before it returned to the Freedom Rides Museum in Montgomery, where it will become part of the facility’s interactive exhibits.

Alabama was one of the places most resistant to racial integration and where some of the most violent backlashes against the Freedom Riders took place, including the firebombing of a bus outside Anniston and a bloody attack on Riders by a white mob of men and women at a bus station in Montgomery. It was also where – when it appeared the Rides may collapse before they could have any real impact – a group of young activists from Nashville picked up the gauntlet to keep the Rides alive. Burks-Brooks was among them.

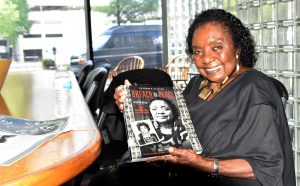

“I do look back at that with pride,” Brooks, now 81, said in a recent interview with Alabama NewsCenter. “That was part of history. That’s the way I look upon it.”

Violence In Alabama

The first Freedom Ride rolled out of Washington, D.C., on May 4, 1961, on two buses, with a plan to challenge segregated interstate busing and bus station rules in a half-dozen states, including Alabama. The Rides were scheduled to end at New Orleans, where a civil rights rally was planned.

The initial stages were relatively uneventful. But the calm was shattered on Mother’s Day, 1961, when one of the buses passed through Anniston. An organized mob smashed the windows and slashed the tires before police escorted the Greyhound out of town. The mob followed, in a line of cars and trucks.

About 6 miles down the road, the damaged bus was forced to pull over. That’s when the mob attacked again, setting the bus on fire with the Riders on board. Several were injured.

Later that same day, just down the road in Birmingham, a separate crowd, including members of the Ku Klux Klan, attacked the other bus at the Trailways station, savagely beating Riders while police, under the authority of notorious City Commissioner Bull Connor, steered clear. Connor had informed local Klan leaders that police would stay away for 15 minutes, allowing time for the attack.

The Freedom Rides almost ended there. But in Nashville, young activists – Black and white – including Burks-Brooks, decided the rides had to go on.

Diane Nash, a leader of the Nashville movement and a close friend of Burks-Brooks, reached out to the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, leader of the Birmingham civil rights movement. Shuttlesworth strongly discouraged the group, saying it was too dangerous to come to Birmingham. But Burks-Brooks, a Birmingham native and student at Tennessee A&I State College (now Tennessee State University), said it wasn’t a case of seeking Shuttlesworth’s blessing. “Diane didn’t ask his opinion. She was telling him.”

By this time, President John F. Kennedy had dispatched John Seigenthaler, assistant to the U.S. attorney general, to Birmingham to ensure safe passage of the original Riders. A native Tennessean, Seigenthaler secured an airplane flight for the Riders, from Birmingham to New Orleans.

Connor and federal officials didn’t know it, but more Riders would soon be on their way to Birmingham to carry on the struggle.

Growing Up Black In ‘Bombingham’

Burks-Brooks has stark memories of growing up Black in Birmingham – considered then by many in the civil rights movement as the most segregated city in America.

From early on in her childhood, Burks-Brooks said, she had a clear vision of the inequities between Blacks and whites, and how things needed to change. She also knew she wanted to be part of making change happen.

She recounted how her mother used to “carry her” from their segregated neighborhood on the city’s east side to shop downtown. She remembers how the white areas surrounding her neighborhood were far more prosperous and better maintained by the city than her own community. She recalls vividly the police car – “it was No. 45,” she said – that routinely patrolled her neighborhood, making sure Black folks stayed in their place. And she remembers how her mother always made her walk in front of her on the downtown sidewalks – instead of beside her – to prevent white folks from intentionally bumping young Catherine aside.

The Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth with Freedom Riders. (Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group. Photo by Robert Adams or Norman Dean, The Birmingham News)

She remembers riding in the back of the bus to get to her Blacks-only elementary school on the city’s south side – the “whites only” signs and inferior water fountains designated for “colored” folks.

“I resented all of that,” she said.

By the time she was a teenager attending segregated Parker High School in Birmingham, she was mounting her own, quiet resistance while white extremists intensified their violent reactions to any challenge to the racist status quo. Indeed, Birmingham had acquired an ugly nickname among journalists and civil rights activists – “Bombingham” – as the Ku Klux Klan and others deployed dynamite (easy to secure in a mining town like Birmingham) to prevent Blacks from moving into white areas of town. One neighborhood in the eye of the storm, walking distance from Parker High, became known as “Dynamite Hill” because of the frequent bombings that took place there.

Burks-Brooks seethed at the indignities Blacks suffered daily in Birmingham. Now, when walking downtown, the teen refused to step aside. One time, she was “bumped hard” by a white man. She was wearing bright red lipstick, and she took pleasure in wiping her mouth on the man’s crisp, white shirt. “He was going to have to go home and explain to his wife why he had lipstick all over him,” she recalled, laughing.

After high school, Burks-Brooks headed to college in Nashville, where she joined other students and young Black activists training in nonviolent civil disobedience and leading local sit-ins at segregated stores and restaurants. They included individuals who would become major players in the civil rights movement, including James Bevel, Marion Barry and an Alabama native and future congressman who would be beaten badly during the infamous Bloody Sunday on the Edmund Pettus bridge in Selma: John Lewis.

Burks-Brooks was enjoying a picnic with some of her fellow student-activists – “we were always celebrating something with a picnic or a party,” she said – when they got word about Freedom Riders being beaten in Anniston and Birmingham. There was no doubt among the group, she said. The Rides had to continue – despite what some of the “adults” said.

“We didn’t pay attention to them, even Reverend Shuttlesworth.”

The group left Nashville by bus on the morning of May 17, 1961. At the Birmingham city limits, police stopped the bus and Bull Connor stepped aboard. Sitting side by side at the front of the bus were Black seminary student Paul Brooks, who would later become Burks-Brooks’ husband, and a white student, Jim Zwerg. Connor asked them to separate – they refused. They were arrested and removed from the bus, Burks-Brooks said.

When the bus arrived at the downtown Greyhound station, just across from City Hall, Connor asked for everyone’s tickets and ordered anyone who came from Nashville to Birmingham to get off the bus. Burks-Brooks and the other Freedom Riders had tickets to New Orleans, so they stayed seated. Connor said he was arresting them – “for our own protection,” Burks-Brooks recalled. They were taken to the city jail.

That night, Connor pulled the group out of the jail (one had already left after being picked up by a parent). Connor said he was taking them back to Nashville. But he actually had something else in store.

Burks-Brooks “went limp – I just stretched out, right on the floor.” It was what the young activists had been trained to do. “They had to carry me to the car.”

The Riders were carried or dragged out and deposited by police into an unmarked car, which turned north. Burks-Brooks was in the front seat, between Connor and the police driver. In the back were the other activists, including Lewis.

Connor had a surprise in store. So did the Riders, and they weren’t sharing it, either.

A Ride With The Bull

Burks-Brooks vividly remembers that night’s ride with the Bull on the dark roads of Alabama – long before brightly lit interstates crisscrossed the state.

The car stopped briefly in Cullman, where Connor picked up a “white preacher” to ride along, Burks-Brooks said. Cullman at that time was known as a “sundown town” – where Blacks were warned not to be found after dark.

Burks-Brooks figured Connor wanted the preacher to come along “so he could be a witness” that the riders weren’t harmed along the way.

The car sped on into Alabama’s rural north. Burks-Brooks and Connor conversed cordially during much of the ride, she said, which stunned a silent Lewis. She said the subjects ranged from the “Dixiecrats” – pro-segregation Democrats who met in Birmingham to officially split from the national party in 1948 (Connor was one of them) – to Burks-Brooks sharing her own, candid descriptions of the many ways life was unequal and unfair for Blacks in the South. She did most of the talking.

“I’d heard about the Bull all my life,” she said. “When I met the Bull, I was ready: I was ready to talk.

“We talked all the way. We talked about our situation, our living situation. We talked about our bringing up. He said we must follow the law, things like that. He was very calm.

“I guess he was calm – he was going to let me run my mouth – because he knew what he was going to do to us.”

Burks-Brooks invited Connor to have breakfast with her when the group arrived in Nashville. Connor accepted.

It was the wee hours when Connor suddenly stopped the car, in the tiny town of Ardmore, Alabama, on the Tennessee state line. Police tossed out the group’s suitcases and Connor ordered the Riders to get out. He said they could take the train back to Nashville from there.

As the car turned to head back to Birmingham, an irate Burks-Brooks couldn’t let Connor have the last word. What she said came right out of the Western cowboy movies that were popular at the time.

“I yelled out to him: ‘I’ll see you back in Birmingham by high noon, Mr. Bull!’”

Standing in the dark along the railroad tracks, the group discovered the building Connor said was a train station was actually a warehouse. What they didn’t know was Ardmore was a town with hardly any Black families.

Burks-Brooks’ mother always told her that whites typically lived on one side of the tracks, and Blacks on the other. The group started walking down the tracks, looking for a Black family to take them in.

“We were just searching, hoping and praying for a place that we could just hide out until we were rescued,” Lewis, who died last year, said in a 2017 article in the Nashville Tennessean.

Eventually they came upon what they believed was a Black household. They knocked on the door, but the man who answered was too afraid to let them in. “Momma told me, always talk to the lady of the house. So, I talked – loud,” Burks-Brooks said.

Inside, a woman was listening. What she said has stayed with Burks-Brooks for 60 years.

“She said, ‘Let ‘em kill ‘em in here.’”

Safe inside, Burks-Brooks called her friend Nash back in Nashville, who sent a car to pick up the group. Soon, they were executing the plan they intentionally did not share with Connor: They were heading straight back to Birmingham.

Back To Birmingham And On To Montgomery

First, the group stopped at Shuttlesworth’s home in the Collegeville neighborhood of Birmingham. Burks-Brooks took a quick side trip to see her mother. The group then headed to the bus station.

More Freedom Riders were coming in from across the country to join the effort. News reporters also were gathering, along with pro-segregationist protesters, who surrounded the place.

There was another problem. Greyhound said it didn’t have a driver willing to carry the Riders on to Montgomery. According to news reports, it took 19 hours for the Kennedy Administration to pressure the company to provide a driver. Burks-Brooks said it was only after a rumor circulated that the feds were flying in a Black soldier to take the wheel that a driver was found.

On May 20, the state Highway Patrol escorted the bus to the city limits of Montgomery, where police were expected to take over the watch. No police were there. At the Greyhound station, an angry mob was growing. As Riders and journalists exited the bus, they were viciously beaten with baseball bats and pipes, especially the white riders. Zwerg had to be hospitalized. Seigenthaler was knocked unconscious while trying to protect a woman rider from attack.

Burks-Brooks bitterly recalls the white women who eagerly took part in the racist thuggery. “I remember the women screaming, “Kill them n—ers! Kill them n—ers!”

She and three other female Riders jumped in a Black cab, but the driver refused to take the interracial group. Burks-Brooks told the driver she wouldn’t leave her white compatriots behind. The entire group got out, but fellow Nashville Rider and activist Bernard Lafayette ordered the Black women back in the car and promised to find safe passage for the white women. Lafayette, a founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) with Lewis, would go on to become an organizer of the Selma voting rights movement.

The attack in Montgomery ultimately sputtered, thanks to the intervention of Floyd Mann, state director of Public Safety, who had been falsely assured that local police would keep order. Mann fired warning shots in the air and called in state troopers to help break up the mob.

The cab took Burks-Brooks to a Black neighborhood where she phoned Shuttlesworth in Birmingham. He arranged safe shelter for the female Riders. But more violence was on the horizon.

The following night, a Sunday, more than 1,000 people packed the Black, First Baptist Church of Montgomery, pastored by the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, to honor the Freedom Riders. Among the speakers were Shuttlesworth and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Outside, an ugly crowd of about 3,000, including women and children, surrounded the church. They started throwing rocks.

Burks-Brooks was inside the church. “I heard a rock hit the window. Some of us got up to look out the window and we got hit by more rocks. That’s when a little fear came,” she said in a public television interview.

Outside, an outnumbered contingent of about 300 U.S. marshals arrived and struggled to hold back the crowd.

King phoned U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy to ask for help. Kennedy appealed to Gov. John Patterson to stop the violence. Eventually Patterson declared martial law in a portion of the city. Alabama National Guard and police moved in to shield the besieged church. Later that night, the guard deployed Jeeps and trucks to safely remove the riders and parishioners.

The Rides Go On

The next day, more Freedom Riders arrived in Montgomery as news of violence at the bus station and the church siege shocked many people in the nation and beyond. Meanwhile, the Kennedy administration had quietly reached a deal with Patterson and Mississippi Gov. Ross Barnett to provide protection to the Riders as they traveled on toward Jackson. The federal government, in return, agreed not to intervene in any arrests when Riders reached the station.

Burks-Brooks didn’t head to Jackson just yet. Instead, she acceded to her parents’ wish that she return to Nashville and take her final exams. She had only a few hours left of coursework to complete for graduation.

But authorities in Tennessee had something else in mind for Burks-Brooks and the student activists. In a matter of weeks, Tennessee State expelled them, which led to a lawsuit that was ultimately decided in the students’ favor. Burks-Brooks received her elementary education degree the following year. More than 40 years later, in 2008, she and 13 other civil rights activists from Tennessee State received honorary doctorate degrees from the university.

After taking her exams, Burks-Brooks joined another Freedom Ride leaving from Nashville. It went straight to Jackson, where she was promptly arrested. Among the dozens of Riders arrested in Jackson through that spring and summer were Lewis, charged with disorderly conduct for using a “white” bathroom, and a student from Howard University, Stokely Carmichael, who became a leading voice in the Black Power movement.

The Kennedy Administration, unhappy with the embarrassing global spotlight put on American segregation by the Freedom Rides, suggested a “cooling off period” to lower the temperature. But Nash and James Farmer, co-founder of the Committee of Racial Equality (CORE) and a key organizer of the freedom rides, said no.

“We’ve been cooling off for 350 years. If we cool off anymore, we will be in a deep freeze. The Freedom Ride will go on,” Farmer said. All through the summer the Rides continued, with activists also conducting sit-ins at restaurants and hotels.

In August 1961, after her time behind bars at Mississippi State Penitentiary, Burks-Brooks married fellow Freedom Rider Paul Brooks in Lancaster County, South Carolina. They stayed at the home of Robert F. Williams, in nearby Monroe, North Carolina, another hotbed of resistance to desegregation targeted by the Freedom Riders.

Williams, a close friend of Paul Brooks, was a more militant activist who headed the NAACP chapter in Monroe. That month, a gun battle erupted in Monroe following the arrest and beating of a number of Freedom Riders. Marauding white supremacists randomly attacked and shot at local Blacks. They returned fire.

“That was a burning town,” Burks-Brooks recalled. She said few people today remember what happened in Monroe that summer. Williams and his wife ultimately fled overseas to escape trumped-up accusations of kidnapping. They remained abroad for years. The charges were later dropped.

Then, And Now

Paul and Catherine Brooks continued their activism, participating in Mississippi voter registration drives and other civil rights actions. In 1962 and 1963, they co-edited a newspaper that reported on the civil rights struggle, the Mississippi Free Press. Among the partners in the newspaper was civil rights activist Medgar Evers, who was assassinated in 1963 by a member of the Jackson White Citizens’ Council.

Burks-Brooks would go on to become an elementary school teacher, then a social worker in Michigan. She later became a jeweler specializing in African jewelry and clothing. She returned to Birmingham in 1979 after living several years in the Bahamas. She retired as a sales manager for Avon cosmetics and then worked as a substitute teacher in Birmingham. Paul Brooks, a businessman and entrepreneur, died in 1989. The couple raised two daughters.

Burks-Brooks still speaks occasionally about her days as a Freedom Rider and activist. “Every now and then, someone will call me.”

She thinks about the dangers she and others faced – staring down official segregation and violent supremacists. She said the inner fire that drove her to defy Jim Crow came from her grandmother in Selma, where Burks-Brooks spent summers as a child. Lively and independent, “Mama” was different than many passive Blacks in that segregated river town, Burks-Brooks recalled fondly. “She would tell you off in a minute.”

Burks-Brooks also thinks about the violence Blacks still face, with the recent deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others. She follows closely the ongoing public dialogue about racial and economic inequality, Confederate monuments and the nation’s legacy of systemic racism.

She said it’s all part of a continuum of racial oppression throughout human history, dating to before slavery in the Americas, and back to ancient societies.

It’s a shame young Blacks still have to be careful, she said. But not surprising.

“Look to that ancient history,” she said. “It’s always been a struggle for freedom and equality.”