By Erica Wright

The Birmingham Times

He was raised in Los Angeles, California, studied in the Northeastern U.S., and traveled the world. But when artist Garland Farwell came to the South, he knew he was home.

“The minute I rolled into [York, Alabama], … I didn’t have any expectations and didn’t even know where I was going,” he said. “But the second I entered town, I knew this is where I wanted to stay, and I knew it was what I needed without even knowing it.”

That was in in 2008, when Farwell became artist in residency at York’s Coleman Center for the Arts—and he’s still in Alabama.

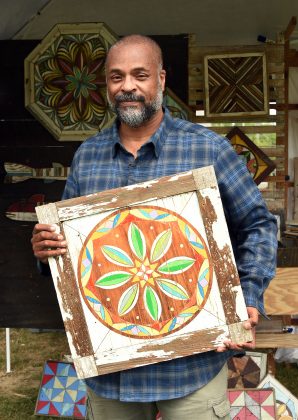

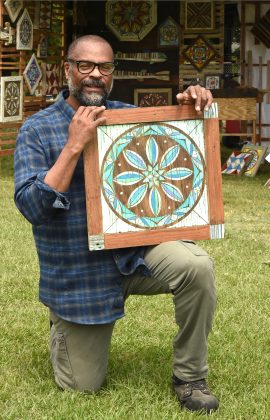

Farwell was the featured artist at last month’s 38th Magic City Art Connection (MCAC) held at the Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark. Though he had participated in the MCAC twice before, this was his first time being selected as the featured artist.

“They reached out to me. I guess the organizers saw my work around and liked it. I don’t know why they chose me, but I appreciate it,” he said. “I’ve done this twice before, and it’s always great. … [The MCAC] is a great show, and they take care of you.”

Farwell’s current work is centered primarily in the studio, developing paintings, sculptures, and assemblages for south17.org, a rural arts cooperative he founded to help foster economic growth in West Alabama. At the MCAC, he showcased his art made from reclaimed materials, including wood and metals that feature intricate designs and assemblages. Each of Farwell’s pieces tells a story.

“It’s really great because as I find wood in abandoned homes or sometimes on the side of the road in junk piles or junk yards, or if people are throwing out things or moving out of their homes, I’m telling the stories of this wood and the families and people who lived in these houses,” he said. “Every piece of wood has a story behind it more and more.”

Art from the Start

Farwell knows what it’s like to live in various places. He grew up as the youngest of seven children in Los Angeles. His father was an officer with the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), and his mother worked for the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Office.

“It was very hard being a Black cop with the LAPD, but my parents were good cops,” he said. “We lived in the community and had a pretty decent and fun upbringing.”

As a child, Farwell developed a love for art.

“I was 9 or 10 when I would just draw,” he said. “I had my little pencil and pen and ink set. I started doing comic books, those preteen comic books, and I would write stories and illustrate them.”

Farwell attended The Athenian School, a college preparatory and boarding school in Danville, California, for middle and high school age students. After graduating in the early 1980s, he attended the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in Providence, Rhode Island, where he enjoyed being around like-minded young people who were focused on and serious about art.

“It was competitive, and it was mind-opening and expansive,” he said. “It was very rich, fun, and challenging to be in that environment. … I’m still very close to a lot of my college friends because that was a real shaping experience for us.”

While at the RISD, Farwell got acquainted with several different forms of art design, including sculpting, video and film, print making, illustration, and painting.

“I studied a lot of different things, but the first year there was the best because I got the foundation and the real core learning that you carry with you forever,” he said. “Nothing beats that foundation year.”

Farwell graduated from the RISD with a bachelor’s degree in art in the mid 1980s. He then made several stops abroad and in the U.S., including stays in Germany, where he did street theatre—“Real, underground performance art for which I made a lot of objects like masks and puppets”—and Ireland, where he did animation work, before landing in New York, where he stayed for about 17 years doing mostly theater, puppetry, visual arts, and teaching.

“I wanted to see what the African American art scene was like [in New York], and it was amazing to encounter so many talented and gifted African American artists,” he said. “I had known them growing up and in college, but not the way I did in New York because you meet everybody there. They gave me the real education.”

Moving South

When Farwell moved to Alabama in 2008, his work centered on a community project on Alabama artist Mose Toliver.

“He was a self-taught, outsider artist, and I wanted to do something that reintroduced him to that community because even though he was from [York] no one knew him,” Farwell said. “I wasn’t sure what I was going to do, but I went into the schools and built objects and puppets based on his paintings. I also did an after-school program at the Coleman Center [for the Arts]. … It was a great mixed-media event [in addition to] a great gallery show, and everyone was very happy.”

Upon completing his residency at Coleman, Farwell did what he could to stay in Alabama.

“I had the credentials and skills to teach other art projects, so I did that off and on for several years in different schools in Choctaw County, Marengo County, and Sumter County,” he said. “I did a lot of great projects and mural paintings, and it was a lot of fun. I loved working with the kids because they have a lot of character.”

The Creative Process

Farwell’s creative process begins with looking for reusable materials first.

“I’m always looking,” he said. “When I’m driving down a road, I might often see a pile [of stuff] somewhere that someone has tossed out or I might see an old house. … If I see a house, I’ll ask around to see who owned it and see if there is something people are trying to get rid of, which they usually are. I find a lot of things on the side of the road. I used to go to a dump, but it closed down. … I’m looking for another local dump I can go to because that was pretty good.”

Because of the type of material Farwell finds, a lot of cleaning is needed.

“My studio is a little bit scary because I have scraped a lot of stuff off this wood,” he said.

Once the wood or metals are cleaned, Farwell begins work on his art.

“Sometimes I have in my mind what I want to make and sometimes I don’t,” he said. “Sometimes, a piece of wood will sit around forever before I know what to do with it, but I do have some favorite patterns and quite often invent new ones.”

Farwell does not have a timeline when he works.

“I might work on one piece, put it down, go work on another piece, then come back to the piece I was working on, so things can take a long time. I couldn’t say how long each piece takes, though. With my assemblages [of wood and metal], those are pretty quick because it’s all the same angle cut that I place differently to give a different look or a different arrangement. Those go pretty fast and are really fun because I do a lot of them. With other pieces, it takes a long time because I have to find the pieces, clean them, arrange them, glue them on separate pieces, and bring them back together so that is a process,” he said.

While some of Farwell’s pieces are different assemblages of wood and metal, other pieces feature intricate quilt block or hexagon design paintings.

“That’s precision painting, so those will take a while because I have to use different tools and elements to create those designs on the wood,” he said, explaining that his work process includes the use of a chain-and-chalk compass, for which he places a nail at the axis to draw his circles, or a straight edge to get drawings on the assemblages. He then uses paints and brushes.

Of all of the works he’s done in his life, Farwell said his current creations have been the most fun and rewarding.

“I love just constantly making things,” he said. “I make them, take them out, sell them, and keep going. … There is no middleman. Thankfully, the work has gotten great reception in general, so I can keep doing it.”

Farwell has received numerous fellowships, residencies, and awards from a range of organizations, including the Jim Henson Foundation, the Franklin Furnace Foundation, the Peg Saandvoordt Foundation, the New York Foundation on the Arts, Diverse Forms (National Endowment for the Arts), the Manhattan Cultural Council, and ArtSpace220.

To learn more about Garland Farwell, visit www.south17.org or contact him at garland@south17.org.

Son of law enforcement

Growing up the youngest of seven children in Los Angeles, California, Garland Farwell got a unique view of law enforcement. His father was an officer with the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), and his mother worked for the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Office.

“It was very hard being a Black cop with the LAPD, but my parents were good cops. We lived in the community and had a pretty decent and fun upbringing,” said Farwell who was the featured artist at last month’s 38th Magic City Art Connection (MCAC) held at the Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark.

Farwell, who currently lives in York, Alabama, said his father was an officer during the Watts Riots in 1965. He had retired before the 1992 Los Angeles Riots took place, and he had a lot of mixed emotions and thoughts.

“It’s not a simple thing to do,” Farwell said of his father’s experience. “There was this sense that he was caught in the middle of a Black revolution and a changing police department. He was part of one of the first integrated units in the LAPD, so getting hired was really difficult; this was before the Civil Rights Movement. … There was never a doubt that we were part of the Black community, but it was interesting because he was the first Black cop to arrive at the flashpoint of the Watts Riots.”

Farwell remembers Black people in the area being very happy to have a Black officer on the beat.

“He had a very proud connection with the community, but there was more disaffection with the way the American social setting was going and how things had to change,” he said. “We never left the community, though.”

Farwell’s mother joined the Sheriff’s Department in 1970, at a time when women weren’t allowed in patrol cars, couldn’t wear pants, and had to keep their guns in their purses.

“She worked at a prison, where she processed prisoners,” he said. “She tried to maintain dignity and ensure that people weren’t abused. … The inmates really loved her because she treated them with respect and humanity. … She’s proud of that legacy of trying to treat people with a little more dignity.”