By Erica Wright

The Birmingham Times

When some of her family members contracted coronavirus last year, Mary Wilkerson knew she would want a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it became available.

“My daughter-in-law came down with it right before Thanksgiving; she didn’t have to go in the hospital and was able to recover. My brother-in-law did not [have to be hospitalized, either]. They had to fight through it, though,” she said.

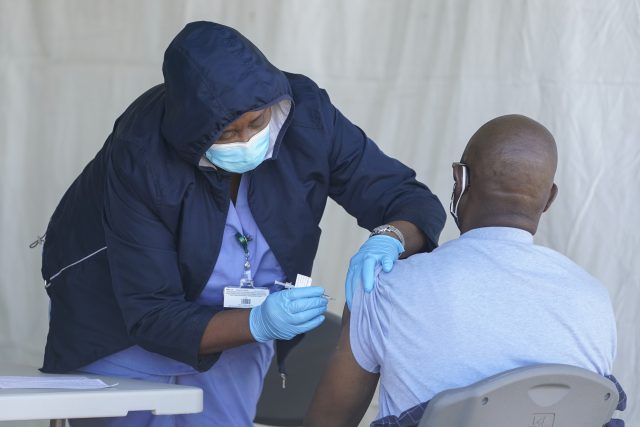

Wilkerson, 66, who lives in North Smithfield Manor in West Birmingham recently received her first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine at the Alabama Regional Medical Services (ARMS) clinic in North Birmingham. Like many African-Americans, Wilkerson said she was skeptical ahead of taking the doses.

“I have some friends who are in the medical field. They assured me that it was safe, and we shouldn’t be afraid to take it,” she said.

That’s the message several leading medical professionals in the Birmingham metro area are trying to get across to residents—especially those in the Black community.

“We understand some of the historical issues that would typically make people in the Black community hesitant [about participating] in trials and studies and receiving injections or medications,” said Vincent Bivins, M.D., chairman of the Department of Surgery at Princeton Baptist Medical Center and president of the Urology Centers of Alabama. “However, we know that these vaccines are reducing infections, reducing the response to infection, and they are also saving lives.”

Underlying Conditions

David Hicks, D.O., deputy health officer at the Jefferson County Department of Health (JDCH), said he’s comfortable that available COVID-19 vaccines “are safe and effective” for several reasons.

“These vaccines have been through rigorous scientific and medical evaluation, and there has been more scrutiny on the safety data from these vaccines than potentially any other medicine or vaccine that has ever been developed—and that’s from the federal government, the research and medical community, and the public health community,” he said.

Three vaccines have received Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and are recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to prevent severe COVID-19 cases; they were developed by Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and Johnson and Johnson.

Dr. Bivins believes Black people, in particular, should get vaccinated because many suffer from underlying conditions that can be exacerbated by COVID-19.

“People who are already immunocompromised or [those] who have pulmonary issues, hypertension, heart damage, or diabetes and are at risk already,” he said. “If they [then] catch the virus, … these are the people it affects [even] more adversely.

“If you can prevent somebody who already has high blood pressure, diabetes, or heart disease from getting [COVID-19], then you are potentially saving lives. That’s why we have to make sure our brothers and sisters are getting in line and getting this vaccine.”

Dr. Hicks agreed.

“African Americans and other minority groups are far more likely to be hospitalized, be sicker with complications, and die from COVID-19,” he said. “With that being said, in order to change that and those numbers, there should be a proportionately higher number of African Americans getting vaccinated to protect the African American community.

“If African Americans get vaccinated less, that is essentially guaranteeing that these disparities in health care outcomes for COVID-19 [infections], complications, hospitalizations, and deaths are going to persist—and it could get worse.”

“Critical Population”

The CDC has highlighted people of color among the “critical population” to vaccinate because they are at “increased risk of acquiring or transmitting COVID-19.” A nationwide report released by the agency on Feb. 1, 2021, estimates that only 5.4 percent of those vaccinated are Black.

In Alabama, 27.8 percent of residents are Black. Through March 25, according to the Alabama Department of Public Health (ADPH), 957,105 people in the state have received one or more COVID-19 vaccine doses. Of those, 15.3 percent vaccinated reported as Black or African American, while 54.4 percent reported as white; 28.1 percent of Alabamians did not report their race.

Even though the numbers of Blacks getting vaccinated seem to be increasing, there is still a lot of work ahead. Erasing the disparity for those being vaccinated is a huge part of the work for area medical providers.

Sandra Ford, M.D., an internal medicine specialist affiliated with Princeton Baptist Medical Center, sees the disparities firsthand through her work with A Promise to Help (APTH), a Birmingham-based nonprofit health care volunteer organization, sponsored by The Spirit of Luke Charitable Foundation and founded by Dr. Ford and her husband, Henry, that works to eliminate health care disparities in the underserved, underprivileged, and underinsured populations in the Black Belt region of Alabama.

“[Blacks] already have pre-existing problems, in addition to multigenerational living, [or families living in one household], which increases our risk. [Many also] have jobs that don’t lend themselves to [working from home],” said Ford, speaking about those who are underserved and underinsured, particularly in the Black Belt. “It is imperative that we educate people on the barriers, including lack of trust or lack of information or misinformation.”

Dr. Ford knows the significance of the vaccine. She had COVID-19 last year.

“COVID-19 can cause so many problems,” she said. “I recently took my vaccine, and it went fine. I had no problems. When my team and I go to the Black Belt [this month], we will have pictures to show that I have taken the vaccine. We [also] will encourage the churches there to talk about [the importance of getting vaccine] and reinforce it among their congregations. … We want to show people why this vaccine is safe, why it is effective, and why they should readily embrace taking it—[because] it could save a life.”

“Informed Decisions”

Dr. Ford, who is planning to open a mobile vaccine clinic in the Black Belt in April, is among those who say a lack of access can contribute to many of the disparities in regard to who receives doses.

“There is a problem in the inner city, as well, with [some] not being computer savvy and some older people not being able to get online and even not having a computer, so there is a large barrier in terms of access,” she said. “Those multiple barriers and not having access … are difficult.”

Dr. Ford added, “We have to alleviate some of these fears and misinformation and enable people by giving them the information to make informed decisions.”

Another difficulty involves access to sites where the vaccines are offered.

“When you look at people who are at risk, they may not have access to transportation,” Dr. Bivins said. “Those things that may seem insignificant can be significant to those [who lack the ability to] get out and get the vaccine.”

In addition to lack of access, Dr. Bivins believes there is hesitancy about getting vaccinated because some in the Black community don’t trust the medical profession.

“When you look at the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, I think that left a huge disdain in the Black community, just being afraid of the health care system and [not wanting] to be guinea pigs,” he said. “If you know the story of Henrietta Lacks and what happened there, where Black people were being subjects of experiments, [those incidents] just left a sense of distrust in the system. I think distrust, in addition to lack of access, knowledge, and education, are the main areas that would allow for the disparity in the percentages of Blacks and non-Blacks getting the vaccine.”

The Tuskegee syphilis experiment, officially named the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male,” was a research project that earned notoriety for its unethical experimentation on African American patients in the South. Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman who lived in Baltimore, Maryland, and was a patient at Johns Hopkins Hospital, unknowingly donated her cells, which were the first and, for many years, the only human cell line able to reproduce indefinitely. Her cells, known as HeLa cells (for Henrietta Lacks) remain a remarkably durable and prolific line of cells used in research around the world.

Increasing Access

Mona Fouad, M.D., director of the Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Center (MHRC) at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), and her team are among those educating citizens about the effectiveness and safety of the vaccines.

“Usually, the vaccines we take, like the flu vaccine, are only about 60 to 70 percent effective. But the [COVID-19] vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna, both of those are 93 percent effective or more, which is really good for combatting the virus,” she said. “Even with Johnson and Johnson, among all who took the vaccine in the studies, [there was] not one case in which [someone who] had COVID-19 had to be admitted to a hospital.”

To increase access, UAB has opened community vaccination sites at the Hoover Metropolitan Complex, the UAB Hospital-Highlands campus, A.H. Parker High School, and most recently Cathedral of the Cross Apostolic Overcoming Holy (AOH) Church of God to help some who “may have educational barriers or may not have access to the internet or devices that allow them [to register to receive the vaccine from medical providers],” said Tiffany Osborne, MHRC director of community engagement.

For example, people can call UAB Hospital (205-975-1881) to register for the vaccine, said Osborne: “We have a program through which our patient navigators are answering the phones … to help provide answers to those who have questions.”

Another strategy to help increase the numbers of people getting vaccinated is by showing community leaders—the mayor, city councilors, doctors, faith leaders—getting the vaccine and talking about the benefits of the vaccine.

“Showing that people of color who are in positions of power or in the health care system are getting the vaccine” builds confidence, Dr. Bivins said.

Pastor Horace Bass, of Olivet Monumental Baptist Church, who is also president and founder of Clergy Concerned for the Community Inc., said he understands the significant role of the clergy in neighborhoods.

“When [pastors] come together, we give our communities voice [and] calm their fears,” he said. “There have been so many untruths told to our neighborhoods, to our people, and they are hesitant about doing anything that people are suggesting, especially when its coming from the side of the road.”

Bass said the clergy have done their own research on the vaccines, including setting up multiple conference calls with doctors about the vaccines, as well as with people of color from different age groups.

“We are pushing it because of the investigation that we have done and knowing, to the best of our ability, that it is safe and is not going to harm people or leave people in a bad state,” he said.

To register for a vaccination, call UAB Hospital at 205-975-1881. To get additional COVID-19 information, call the UAB GuideSafe Hotline at 205-934-SAFE (7233).