UAB News

The sheer scale of the GuideSafe Entry Testing initiative is staggering. Part of the multi-tool GuideSafe platform — a partnership between UAB and the Alabama Department of Public Health that has received more than $30 million in CARES Act funding from Gov. Kay Ivey — Alabama’s GuideSafe Entry Testing is the largest higher-education testing initiative in the nation.

The testing is free — and required — for any student attending a public or private four-year college in Alabama and all two-year college students who reside on campus. That is more than 200,000 students, who will be tested at 15 locations around Alabama — in addition to thousands of out-of-state students, who will use at-home collection kits mailed to their homes.

How will that work, exactly? And how are UAB labs, the site of the bulk of this testing, able to offer test results to students in 24 to 48 hours, when many commercial labs in Alabama and elsewhere are reporting delays of a week or more?

Two of the GuideSafe initiative’s leaders from the UAB Department of Pathology – Chair George Netto, M.D., and Assistant Professor Sixto Leal Jr., M.D., Ph.D., who developed the testing strategy – shared details during a virtual press conference Aug. 5.

The pathology department has been running upward of 1,000 COVID-19 diagnostic tests per day for patients and staff at UAB, along with affiliate hospitals and other partners across Alabama, Netto said. With the GuideSafe initiative, the department expects to complete up to 10,000 additional tests per day, while still running the same 1,000 clinical tests per day (or more).

Pooled testing, UAB-developed and -produced test kits and hardworking staff have made this possible, Netto and Leal explained — along with new technology and strategic partnerships.

Pooled testing

The scale of GuideSafe called for an entirely new strategy. One key element: Because all students being tested will be asymptomatic, the expected incidence rate — the number of students expected to be diagnosed with COVID-19 — is low. (Students who have COVID-19 symptoms will be referred for standard clinical testing.)

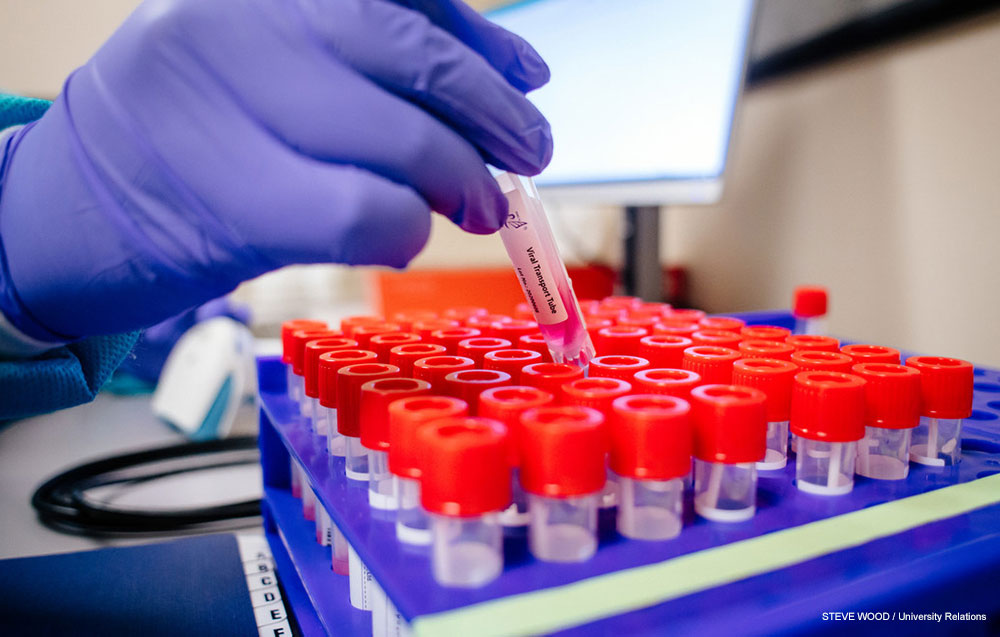

That low incidence rate led the pathologists to choose pooled testing — combining samples from multiple patients together and testing them all at the same time. If the test is sensitive enough, as UAB’s is, it will still identify any positive samples in the batch. But if all the samples are negative, the lab will reduce the number of tests needed many-fold. Major commercial laboratories, including Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp, as well as other academic medical centers, are now using pooled testing, Leal said.

At the moment, with the incidence rate of 1.5% seen in pilot testing conducted this past week, samples from eight different patients are being tested together, Leal said. “With a 1.5% incidence rate, if we pool eight samples together” and run 100 pooled tests with eight samples in each, “we are expecting 12 of those pools to be positive,” he said. That would mean that 96 individual samples — eight samples times 12 pools = 96 — would each need to be tested separately to identify which patients from those pools were positive and which were negative. “If we perform 196 tests” — the 100 original tests plus the 96 extra tests needed to identify individuals from the positive pools — “we can report out 800 results with high confidence,” Leal said.

When a pool comes back negative, all eight students in that pool should receive that result within 24 hours, Leal said. The extra time needed to run additional tests for pools that are positive will mean students in those pools will receive results within 48 hours.

“Right now, we are able to do about 6,000 tests per day,” Leal said. “Depending on the incidence rate, we are able to go up or down” — increasing the tests daily if fewer students are returning positive results, or running fewer tests if the incidence rate becomes higher.

UAB-made test kits

A major limiting factor in testing worldwide has been the tight supply of the specialized chemical reagents needed to make the tests work, Leal said.

So the pathology department developed its own kits, using different reagents with a more stable supply chain. They were assembled at UAB and are taken directly to the GuideSafe collection sites around the state.

These kits make GuideSafe Entry Testing less susceptible to shortages. They also are significantly cheaper than commercially available kits, Netto said. The CARES Act funding supporting the Entry Testing initiative, even at $20 million, could not cover the costs of 200,000 normally priced kits. “These tests are probably five- to six-fold cheaper than if we were to use a commercial test,” Netto said. They have undergone rigorous testing, Leal added. “The tests are very sensitive…. The primers and probes used in these tests are very specific to the virus,” he said. “We have obtained Emergency Use Authorization approval from the FDA for this test and have validated pooling over eight weeks.”

The sensitivity of the test is above 92%, as high as 95%, “with a perfect negative predictive value, which is really what you want,” Netto said. “When we dilute a sample 1:8, which is what we are doing, the sensitivity is still comparable” to other FDA-approved diagnostic tests, he said.

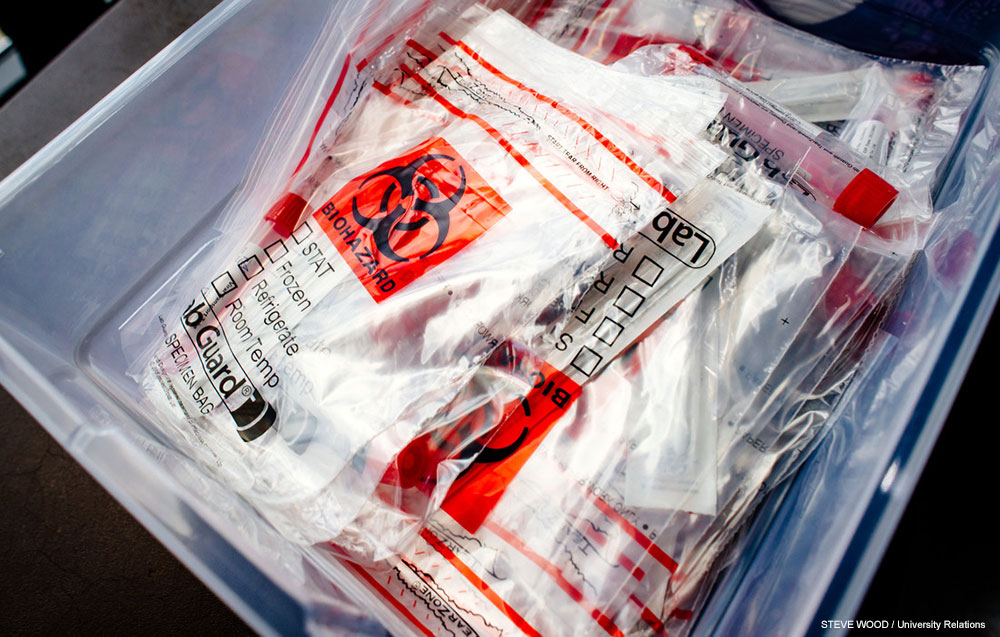

Nasal swabs

The GuideSafe Entry Testing initiative is using self-administered nasal swabs to collect patient samples. These are very different from the nasopharyngeal swabs, administered by a health care worker, seen in many media reports of COVID-19 testing. The nasopharyngeal swab, “nicknamed the brain biopsy,” Leal said, “goes all the way back to the nasopharynx,” the part of the throat that sits behind the nose. “The nasal swabs we are using are less invasive — they go about one inch into each nostril,” Leal said. This means there is less discomfort for the test-taker and “significantly less risk for staff,” who will observe the self-collection and offer instruction but do not need to handle the samples directly.

Research shows that nasal swabs are about 90% as sensitive as the nasopharyngeal swab, Leal said. They “work very well for this purpose,” he added. “Even if somebody has very little virus in the nose, it will be detected.”

A 24/7 team

Leal’s lab in pathology does not normally operate 24 hours a day, but that has become the norm since COVID-19 arrived in Alabama in March. “We test around 1,000 samples a day and… 99% of the samples we report back in 24 hours,” Netto said.

“We have six full-time staff…. [who] have been working very hard since March,” Leal said. “We have recruited an additional 17 individuals for this initiative.” These are individuals specializing in molecular biology and microbiology at UAB “with exceptional talent to be able to help this initiative for pooling, for extracting RNA and for RT-PCR,” or real-time polymerase chain reaction, the technology used to identify the genetic material of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, in the form of RNA, in patient samples.

“The lab is extremely busy,” Leal continued. “We are a 24/7 operation to get that 24- to 48-hour turnaround time for this initiative.”

This will not affect the clinical testing for UAB patients, staff and affiliate hospitals that continues unabated by a separate team, Netto emphasized. “They are two totally independent processes,” he said. “Our patients are our primary concern. While this is a very important initiative… [we required] that if we were going to tackle this, it should not impact in any way our clinical testing.”

Strategic partnerships

In order to track hundreds of thousands of samples and results, UAB partnered with lab management company Ovation to develop an information technology infrastructure to efficiently organize and manage sample tubes and link results to digital records.

To handle reporting of results at massive scale, while maintaining HIPAA privacy standards, GuideSafe is working with several commercial partners specializing in logistics, including the Google-affiliated Verily and PWN.

Benefits beyond UAB — and college students

The benefits of the GuideSafe Entry Testing initiative spread far beyond UAB. The pathology team is training colleagues at the University of South Alabama in the techniques and processes involved. And in a few weeks, once higher-education entry testing is wrapping up, the same platform can be opened to businesses and communities around the state, Netto said. This could allow Alabama to establish widespread sentinel testing of the type that has already begun at UAB. Some 4% of students, faculty and staff on UAB’s campus are being tested weekly in order to identify virus hotspots and intervene before they spread further.

UAB’s pathology department, with 89 faculty, is one of the largest in the country, Netto noted. But pathologists around the world have been contributing on the front lines of the fight against COVID-19 and earning “overdue credit” from their colleagues for their crucial role in the health system, he said. “We pride ourselves, as being a state public school, to help the state and community,” Netto said. For pathologists, “this gave us the opportunity to shine.”