By Je’Don Holloway Talley

For The Birmingham Times

There were five kids in the family. There was one breadwinner, the father, and sadly, he was an alcoholic.

Hunger, remembers James Harris, who was one of those kids at the house in Houston, Texas, could come knocking at the door on any old night. School lunches were a lifeline.

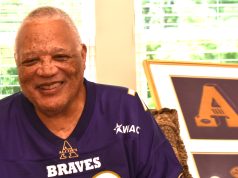

Today, Harris is founder, president and CEO of Harvest Community Charities — HCC, for short. The cleaned-out cupboards and vacant refrigerator of his childhood do much to inform his worldview.

HCC is on a mission: to end food insecurity and break the generational cycle of poverty. On its roster of clients are faith-based and independent pantries all over central Alabama, and a vast network of Southern Baptist and African Methodist Episcopal churches.

HCC helps connect food pantries with national wholesale suppliers, and combats health disparities by providing nutritious food. “Where the pantries buy food from is a quality issue,” the 62-year-old Harris said. “HCC has helped correct those problems.”

He said, “We have a warehouse in Pelham where our partner pantries come to pick up food, and they take those items back to their local pantry and distribute to those in need within their neighborhood.”

‘A completely new concept’

The vision for Harvest Community Charities began forming for Harris in Kansas City, Missouri, when he was the executive pastor at Harmony Vineyards Church, shepherding a growing congregation. “I saw the tremendous need in food, and where food was coming from was not giving people a nutritious wholesome meal,” he said.

Local charity groups filled in some of the gaps, but they’d run short, too, never seeming to have enough donors. “I began by inquiring of the Lord ‘Isn’t there a better way to do it than what I’m seeing?’” Harris said.

“There certainly isn’t a shortage of food, it’s the way the system is built and the way that food is handled,” Harris said. “That started me down this road.”

In a sense, he went back to his roots, he said. Those roots didn’t trace only to the megalopolis of Houston, Texas. They tracked also to the tiny town of Minden, Louisiana.

For much of his boyhood, Harris’ family lived in Houston’s 5th Ward, a hard-luck and oft-neglected expanse of the old core city. “It was drug-infested, and crime was very high,” Harris said. “It was unsafe in school and walking the streets.”

Then, tragically, his mother died when he was just 11. Harris and his brothers and sisters soon found themselves on the way to Louisiana, moving in with their aunt and uncle, and their twin sons, on a little farm.

As Harris put it, “Everything went from 100 miles an hour to 10 miles an hour.”

Remarkably, to Harris, his aunt and uncle raised their own food. “This was a completely new concept for me,” Harris said.

The farm wasn’t much, just five acres, given courtesy of a wealthy nearby landowner nearby for whom his uncle toiled.

But the farm life in Minden, said Harris, was a revelation to the kids fresh from Houston, instilling values and work ethic. “We were given the ability to help provide for ourselves,” he said. “Using our own hands to raise the crops ensured we would never go to bed hungry again.”

He said, “I understand and appreciate what the ground produces. There’s something mystical and magical about seeing a seed go into the ground and watching it sprout.”

Admittedly, the hours between sunup and sundown could be tough and wearying. “We would get up early in the morning and go farm the land, it was very hard work,” he said.

His uncle, cautious about parting with any dollars, didn’t buy a tractor until Harris was in high school. “We would plow the land with a mule and a horse to grow corn, peas, sweet potatoes, red potatoes, butter beans, greens, squash, tomatoes, bell peppers, peanuts and okra,” he said. “As far as livestock, we raised chickens, pigs and cows.”

The winter time was slaughtering time. “We’d smoke our own hog meat,” Harris said.

At age 22, by then deeply familiar with every side of farm life, Harris opened his own grocery store in Minden, running it for five years before moving into a manufacturing job.

Looking back, Harris said, “I can clearly see how my personal experience and hand in growing and producing food gave me a love for the food industry. It’s no surprise that the Lord led me into a lifetime career working in that sphere, and into a ministry so intricately intertwined with fighting food insecurity.”

‘God’s Power’

In 2012, Harris arrived in Alabama from Missouri to become vice president of sales and marketing for Belle Foods, which had purchased the Bruno’s Market franchise. By then, he’d already formed Harvest Community Charities, and it soon became his entire focus.

A key goal, at that point, was to expand HCC’s chain of resources and its family of associated pantries. Harris was determined not to get stuck relying on donors’ leftovers. “I would never give anyone food that I wouldn’t eat myself,” he said.

“We buy from the same systems and suppliers that grocers buy from. We’re not doing produce at this time because we don’t have a cooler, but we do frozen meats, we have a supplier that takes care of that for us, we do canned goods, and shelf-stable foods,” Harris said.

He said HCC’s team of 100 plus prayer partners also play a vital role. “Prayer is more important than anything else because you’re going after territories that will change people’s lives,” he said.

The prayer partners, he said, “are calling on God’s help to move in the areas where we are working.” He continued, “We would not be here if it were not for prayer. We do newsletters that we share with our intercessors…and messages come from God at very strategic times. We all need God’s power and protection to move in His love for those we serve.”

On the home front, Harris is a husband, the father of two and the grandfather of four. He and wife, Wanda, have been married for 42 years. Their sons are Christopher, 40, and Jonathan, 32.

Harris said he’s writing a memoir that he plans to share with his family’s new generations.

So what’s next for Harris and Harvest Community Charities?

Right now, there’s the COVID-19 pandemic to cope with. It has affected HCC’s food supply and put new strains on its charity partners as more people come looking for help. “We have been able to keep up with the demand,” Harris said. “Fortunately for us, our supply of food does not come through the conventional supply channels that most food pantries use.”

Further into the future, HCC would like to help communities equip and empower themselves to break the cycle of poverty in food deserts. Several initiatives are already in play.

For example, HCC plans grocery stores in impoverished areas that will open access to quality, fresh fare, and as well as to stable jobs within the stores. “We help them equip and train their hires with invaluable skills and experience which will serve them throughout their entire careers,” Harris said.

HCC is also developing a program to help young people identify what sorts of careers will truly be fulfilling to them. “We want to help them discover career interests and make career choices early, because all tangible careers are not necessarily college driven,” Harris said.

Learn more about Harvest Community Charities

On the web: https://hccharities.com/blog/provisions-harvest

On Facebook and Instagram: @harvestcommunitycharities

On Twitter: @harvestccpr