By Sherrel Wheeler Stewart

For the Birmingham Times

Mark Sullivan was fresh out of Alabama A&M when he landed his first teaching position with Birmingham City Schools (BCS) in the early 1990s. He was hired as a long-term substitute teacher to fill in for someone on maternity leave.

It was December when the principal showed him his new fourth-grade classroom—a trailer in the rear of North Roebuck Elementary School. Before the next semester began, Sullivan and his mother, Odessa Oliver, spent a weekend decorating his new classroom. She, too, was an educator, and had retired after teaching in Birmingham for 27 years.

Sullivan said he wanted that classroom to send a message about learning: “Even though I was the substitute until the end of the year, we wanted it to look a certain kind of way because we had expectations for all of the students,” he said.

In May of this year, Sullivan was named BCS interim superintendent, following the resignation of Superintendent Lisa Herring, who went on to lead Atlanta Public Schools.

Sullivan, born and raised in Birmingham, has worked his way from the classroom to the superintendent’s office. He said he still has expectations as he leads the system in one of its most challenging periods in recent years.

Speaking at a press conference after his interim appointment was announced, Sullivan said, “We are in the midst of unprecedented times. … I am very thankful that the education I received in BCS, the preparation I have received at what I feel like are some of the best universities in the state of Alabama, and the experiences I have gained in BCS as a teacher, as a principal, and as a district leader have prepared me for this moment.”

The COVID-19 pandemic forced schools across Alabama to close in March, and virtual learning replaced traditional classroom instruction. But studies show about a fifth of Birmingham students don’t have internet access.

And despite the early end to the school year, Sullivan and his team still must handle retirements and hiring in time for the first day of classes in August. There’s also the task of replacing books, as well as getting electronic tablets and other tools for the students and staff.

Sullivan, a veteran educator and retired U.S. Navy reservist, is fixed on tackling a tough job.

“Teaching and learning will happen on the very first day,” he said, sitting in the library of Woodlawn High School, which he graduated from in 1985. “We will be ready—whether we have traditional or virtual classrooms.”

In addition to his classroom and school administration experience, Sullivan relies on lessons learned in the military to help guide his leadership style. He joined the U.S. Navy Reserves to help pay for his college education, but he learned some valuable lessons there, too.

“I learned the importance of working as a team, listening to your people, having high expectations of all—especially for yourself—and that good morale is important to the success of any organization.”

In the Beginning

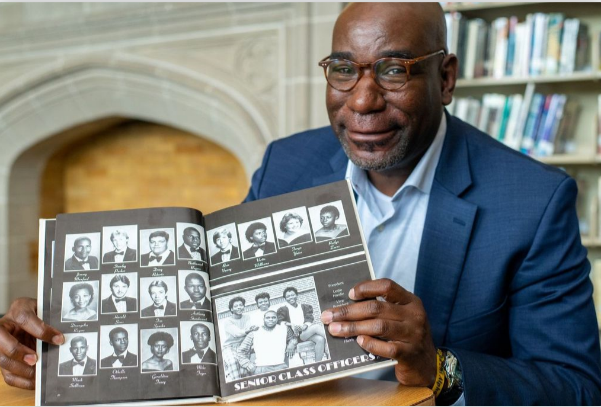

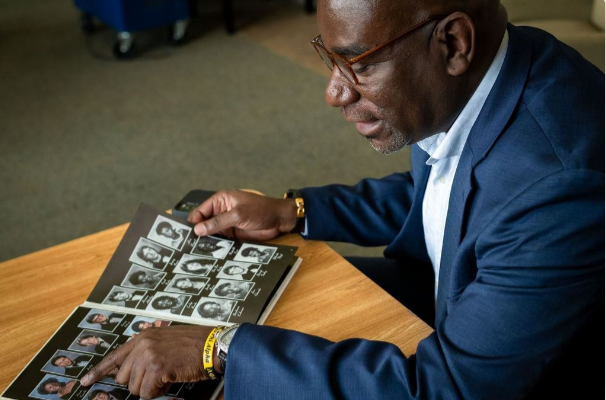

During a recent interview with the Birmingham Times, Sullivan pulled the 1985 Woodlawn Colonel yearbook from a shelf and flipped through the senior section, where he found his black-and-white photograph. His hair was wavy, and he wore a bowtie. Some of the student pictures were in color, but his was not.

“Back then, I couldn’t afford to have my picture in color,” said the 53-year-old Sullivan, who still has fond memories from Woodlawn and from his elementary school, Riggins in North Birmingham.

Although he was thin, Sullivan played football and was a receiver during his first two years of high school. He gave up athletics to get a job bagging groceries at a nearby Food World supermarket, so he could save money to buy a car—and he did. That blue 1977 Oldsmobile Cutlass was the car Sullivan had when he went to college, he said.

At Riggins, Sullivan recalled a nurturing community of support that included an influential male teacher. While he comes from a family or educators and other school employees, his eighth-grade science teacher, Carl Evans, was the man who helped him see education as a possible career choice.

“You know how it is sometimes. That one male teacher in the school gets to do a little of everything,” Sullivan said. “Mr. Evans was the basketball coach. He was the Boy Scout leader. He was the eighth-grade science teacher. I remember going on a scouting a trip to Oak Mountain State Park. That’s when I caught my first fish.”

At Woodlawn, he recalled teachers who were passionate about their work and demanded that students memorize some of the greatest passages from renowned authors, like William Shakespeare and Edgar Allan Poe.

He still recites one of Poe’s poems, “Annabel Lee”—“I and my Annabel Lee. We loved with a love that was more than love.”

The words from one of Shakespeare’s plays, “Macbeth,” roll off his tongue—“Life is but a walking shadow. … ”

Sealing the Deal

Sullivan’s first career choice was dentistry. He wanted to attend Alabama Agriculture and Mechanical University (AAMU) and go on to Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee. That path didn’t work out the way he had planned, but he knew he had a passion for teaching and learning. His first assignment at North Roebuck, although temporary, sealed the deal for his future.

“I was just so impressed, first to have a job,” Sullivan said. “I think I may have been the first male teacher for some of the students. They looked at me like I was a unicorn.

“I loved that job and just about every other job I’ve ever had—whether I was the teacher, principal, assistant superintendent, director, or chief of staff.”

Sullivan’s first full-time assignment was at Dupuy Elementary School, teaching fifth grade. That year former principal and school administrator Samuetta Drew said she hired three male teachers, including Sullivan. From the beginning, Drew said she noticed Sullivan’s energy.

“He would never sit down when the students were in the classroom,” Drew said. “He moved around, working with students.”

Dupuy had a strong staff, and the school was known for its academics and some special programs, such as its etiquette program, which gained national attention with stories reported by the Associated Press and CNN.

Around that time, Drew recalls Sullivan telling her he wanted to be a principal one day, and she became his mentor. Sullivan later worked with Drew at Center Street Middle School and on the leadership team in the school system office. Along the way, he also served as principal at Glen Iris and Spaulding elementary schools, J.W. Phillips Academy, and Ramsay High School.

Sullivan, who is divorced and has a 14-year-old daughter, spent 24 years in the U.S. Navy Reserves as a corpsman. He was deployed twice but did not see combat. He also worked stateside in military hospitals in 1990 and again in 2003.

“[Sullivan] has an emotional and compassionate side, but he also is no-nonsense,” Drew said.

Local Schools

Jerry Tate was PTA president during Sullivan’s years at Phillips Academy. He credits Sullivan with helping him make the decision to enroll his daughter in the school, which was just getting started at the time. Phillips closed as a high school in 2002 and reopened in 2007, with a plan of offering a more robust curriculum and strong parental involvement.

When Tate met Sullivan, “He was selling a vision to something that did not even exist. It was so strong and compelling that I did not think twice,” Tate recalled. “I was one of the first parents in line when they opened up the application process.”

While Sullivan was successful at Phillips and at Ramsay, Tate said the educator has a much greater challenge leading the entire system.

“Before, he had to be concerned with only 700 students,” Tate said. “Now he is responsible for 20-something thousand.”

BCS had more than 22,000 students in the last school year, according to the Alabama State Department of Education.

“[Sullivan] has to try to make sure each one is successful,” Tate added.

Drew said Sullivan’s success in Birmingham sends a message to others who work in the BCS system.

“It means a lot to be from the system—teachers, classified employees, they all want to know and feel like they have the ability to promoted, as well,” Drew said. “[The school board doesn’t] have to go outside of the district to find someone to recognize for their talents, their skills, their intellect.”

Sherrel Wheeler Stewart was named this week Executive Director of Strategy and Communications for the Birmingham City Schools after the planned publication of this story.