By Barnett Wright

The Birmingham Times

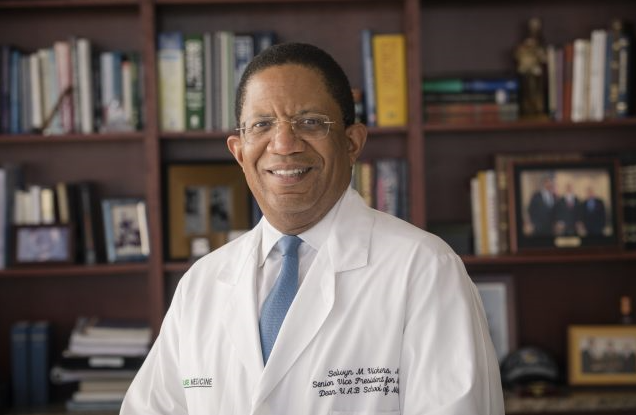

COVID-19 can significantly kill more people than the flu; blacks and the poor tend to do much worse when infected with the coronavirus; and physicians and nurses are working in a frightening environment, said Selwyn M. Vickers, MD, senior vice president of medicine at UAB.

Vickers, who is also dean of the UAB School of Medicine, spoke during a livestreamed panel discussion hosted via Facebook Live by the Housing Authority of the Birmingham District (HABD) as well as in an interview with The Birmingham Times.

“At UAB, we have about 58-60 patients in the hospital who have been diagnosed with the coronavirus,” Vickers said on Monday. “At any given time, just short of 30 of them are on a breathing machine.”

During the panel discussion, Vickers said “[COVID-19] really has a significant ability to damage the lungs. It also has a significant ability to weaken the body once [a person] gets very sick and requires ventilation, which is a very invasive procedure and therefore increases the risk of dying.”

Blacks Tend to Do Worse

Blacks and the poor seem to suffer more, or do less well, with the virus, Vickers said.

In Alabama, African-Americans make up 37 percent of the confirmed cases of coronavirus, and represent 27 percent of the state’s population. Among deaths, 44 percent of the 39 Alabamians who’ve been verified to have died due to coronavirus were black, the same numbers as whites, according to the Alabama Department of Public Health.

Data released by the Louisiana Department of Health this week showed black people account for 70 percent of coronavirus deaths in the state, despite making up just 32 percent of the population.

In Michigan and Illinois, African Americans account for about a third of coronavirus cases and about 40 percent of deaths, even though that demographic only makes up 15 and 14 percent, respectively, of the states’ total populations.

Vickers said, “There are reports now of data coming from areas of high density populations where African-Americans live – Chicago, Milwaukee, New Orleans – demonstrating that in these areas where there are x amount of African American citizens there is disproportionate number of them who have actually gotten infected. And that is becoming quite evident.”

“I will give you two firm examples,” he said during the recent online event. “Milwaukee and Detroit are probably the most prominent examples because these states count not only people who get the respiratory infection but also who they are and where they are from — they count whether they are African American, Latino, white, or something else.

“In Milwaukee, which is 26 percent African American, 50 percent of the COVID-19 cases happen to be among African Americans. The other astounding statistic: Even though another 50 percent of the people who are white or Latino who get it, of the 50 percent who are African American who get it, 80 percent of the people who die are black.”

Vickers added, “You can hypothesize that they have some of these chronic illnesses,” such as diabetes, hypertension, or heart issues. “You can worry that they don’t have access or don’t get to the hospital as early. There are probably multiple reasons. And in Michigan, where only 14 percent of the population is black, nearly 35 percent of the [COVID-19] cases are among blacks. More concerning, 40 percent of the deaths are among black people. Not only can we get it, but we tend to do much worse when we do get it.”

Frightening Environment

Doctors, nurses, and other medical staff are working in a critical environment, Vickers said.

“The people you will depend on to take care of your mother, your grandmother, your father and even you if you get ill are these healthcare providers and doctors,” he said. “If they can’t function because they are sick, if they can’t function because they are admitted themselves, if affects all of us.”

During the Facebook Live panel discussion, Vickers explained, “Whether you have one COVID virus patient or a thousand, [there] is the risk of health care workers getting infected. Our physicians and nurses are in many ways in a frightening environment because they are trying to serve and keep someone else alive, yet they know they put themselves at risk of getting infected. … If you’re not around a person with the virus, you probably won’t get it.

“But if you’re in the hospital directly in contact with and trying to take care of [an infected person], you have a higher risk of getting it. You don’t automatically get it just because you come to the hospital, but those providers have a significant risk.”

In addition to care for patients “we clearly think hard about how we protect our doctors,” Vickers said. “Having enough of this personal protective equipment (PPE) is really important. . . it is at the forefront of how do we make sure we protect our staff, our nurses, our providers who may be physicians or nurse practitioners. We want to make sure we are being very careful.”

Vickers said he observes both doctors and patients as he regularly visits several dozen rooms in UAB’s intensive care unit.

“On a daily basis, we get new patients,” he said during the livestreamed event. “And often, in similar numbers, we see health care workers who may also be infected. It is both sad and troubling to see individuals who are seeking to do good also put themselves at risk.”

Each day, there is an increase in the number of cases of virus infections, Vickers said. As of Tuesday, April 7, there were 2,197 confirmed cases of coronavirus in Alabama, including 461 in Jefferson County. There are now 39 confirmed deaths statewide from the illness. On March 11, there were zero cases.

Influenza vs. Coronavirus

There are similarities and differences between the flu and the novel coronavirus.

“Covid-19 is worse than influenza for multiple reasons, including there is no proven therapy” for the flu, he said. “We have some medications we have used for the flu that have been effective [For example, the antiviral medication oseltamivir phosphate, sold under the brand name] Tamiflu, and there are a couple of other new ones on the market that actually work. We have no effective therapy for COVID-19 . . . [and] because we have no therapy it’s 10-20 times more lethal.”

COVID-19 will also kill significantly more than influenza because of where it infects, Vickers said during the online panel discussion.

“The flu [mainly] infects the upper airway and most often stays there, but on some occasions it goes deeper into the lungs and can cause difficult pneumonia, [infection in one or both lungs],” he explained. “This coronavirus [on the other hand], … infects the lower part of the airway. In that process, when [a person gets it], early on it automatically causes pneumonia. … It typically starts with a small pneumonia, which is why so many people get intubated,” which is “the placement of a tube into the trachea (windpipe) in order to maintain an open airway in patients who are unconscious or unable to breathe on their own,” according to the Encyclopedia of Surgery.

The similarities between the two illnesses, according to Vickers, are that “the major area of transmission comes from the back of the throat and the lungs, and most people get well and get over it.”

Still, he added, “You’ll probably be surprised [to know that] we lose about 50,000 to 60,000 people a year who have very bad influenza.”

Given the grim numbers, Vickers said public information and public behavior are critical tools in fighting any pandemic or community-borne virus. Medical experts at UAB and across the country are encouraging several common principles to reduce the spread of the coronavirus, he said: Avoid large gatherings; maintain a social distance of six feet apart; wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds; cover your nose and mouth with a mask; disinfect surfaces and places you frequent on a regular basis; and, most importantly, stay at home as much as possible.

Dr. Vickers provides insights about:

Hydroxychloroquine

“Hydroxychloroquine is being used as part of our therapeutic options for taking care of patients. It is, most importantly, being used in clinical trials to determine its true benefit. There are trials we will be participating in that actually involve health care workers potentially given [the medication both] before and after they are exposed to determine the full benefit: Can it prevent? Does it actually treat? That is yet to be completely determined.

The drug has a known benefit for people who have lupus and rheumatoid arthritis and you have people in our community with that. When you basically consume the drug by having people either write prescriptions for it, order it or quarantine it from the rest of the market the people who we know need the drug can’t find their medication.

Testing

“Testing has been a conundrum for our country and for our region. There are multiple people working to simply try to get testing done more broadly and in a manner that improves turnaround times. … It’s still a process of improvement, particularly for community-based testing, … but I think those will happen at a faster time period.”

Homemade Masks and Gowns

“What we’ve known from other countries, what we’re learning from our own data is that anywhere from 20 to 40 percent of people who carry the virus have no symptoms at all. They don’t know they have it and you don’t know they have it.

One of the things that helps us fight this and prevents its further spread is for people who feel that they are fine . . . the problem is they don’t know who they are, nor do we. That’s why we ask everybody to wear some type of barrier mask. It’s not trying to create a resistance from an infection coming to you but largely because we know the virus can spread through talking . . . it’s our best mechanism because we don’t know who is an asymptomatic carrier to have people limit the risk of people actually spreading the virus unknowingly.”

Respiratory Symptoms of Possible COVID-19

“Early symptoms of the illness: You feel tired; you have a fairly high fever, usually as high as 101 degrees; and you feel fatigued. Then, over some short period of time … usually overnight, you begin to have a cough. That’s the earliest respiratory symptom because you have an irritation in your airway. You cough constantly … and really feel like you can’t get your breath. When that gets significantly worse, to the point where you feel you can’t walk very far or you feel like you’re losing your breath, you clearly need to seek medical help. Many people who have a cough and a fever and feel tired and a little short of breath will do fine at home, but that can progress to a degree where you don’t feel well or you feel like you can’t get air into your lungs. That’s when you clearly need to go to the emergency room or the hospital — maybe even earlier if you have diabetes, renal [kidney] failure, or heart disease.”

Hospital Capacity

“Right now, we have 58-60 patients in the hospital, just short of 30 whom are on ventilators. We have plenty of beds for people who need care and need that space. Though [the increase in patients] does tax our intensive care units [ICUs], we have plenty of ICU space if people need it.”

Where to Get Help

The Alabama Department of Public Health’s Coronavirus Hotline is available 24-7. For information about testing, call 888-264-2256; for general COVID-19 questions, call 800-270-7268.

Symptom Checker

The new website, HelpBeatCOVID19.org, will provide public health officials insight into underserved areas based on the symptomatic data collected from the region and could help inform and enhance public health observation.