By Wilson Fallin Jr.

University of Montevallo

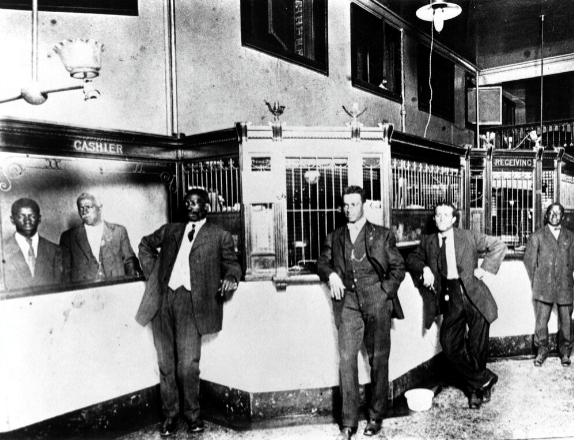

The Penny Savings Bank, founded by Reverend William Reuben Pettiford in Birmingham on October 15, 1890, was the first black-owned and black-operated financial institution in Alabama and one of the first three in the United States.

Created as a necessity of de facto and later codified segregation, the bank backed and encouraged development of black businesses, especially in urban areas, as well as savings by African Americans, until its closing in 1915.

The bank’s first building, a three story stone and brick structure, was located at 217 18th Street North. In 1913 the bank constructed a new six-story building one block north, now known as the Pythian Temple.

It was built by the black-owned Windham Construction and some have identified its style with the work of African American architect Wallace Rayfield, who kept an office in the building for a time. The bank did provide financing for many of the homes that Rayfield designed for Birmingham’s black professionals.

Pettiford, the founder, provided the initial $2,000 in capital. Other officers included physician Ulysses Mason, Indianola banker W. W. Cox, and an unnamed saloonkeeper. In its early years the bank’s officers did not take salaries, helping the bank survive the 1893 panic which spelled failure for other institutions.

About Pettiford

Pettiford was born to free parents in North Carolina in 1847. He moved to Alabama in 1869 to seek better educational and financial opportunities. After seven years of studying while holding down jobs, Pettiford completed his degree at the Lincoln Normal School (a predecessor of Alabama State University) in Marion, Perry County.

In 1877, Pettiford became a teacher at Selma University and simultaneously entered the theological department of the school, taking courses from President Harrison Woodsmall. Three years later, he voluntarily severed his connection with the school to become pastor of the First Baptist Church of Union Springs, where he also served as principal of the city school for African Americans.

In 1883, he accepted the pastorate of the First Colored Baptist Church of Birmingham, later named the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, at the urging of state Baptist leaders and educator Booker T. Washington, who assured him that he could provide necessary leadership for Birmingham’s expanding black population.

Impetus To Establish Bank

Pettiford’s motivation to establish the Penny Savings Bank came from several sources, including his former position as financial agent for Selma University and his growing friendship with Washington, who was a strong advocate of thrift and self-help for the black community. Pettiford related how, while riding a streetcar one Friday night, he observed an African American woman drinking whisky after receiving her weekly pay. That experience led him to think about establishing a business where blacks could save their money rather than waste it.

Another impetus came from William Washington Browne, president of the black-owned Savings Bank of the Grand Fountain United Order of True Reformers of Richmond, Virginia, who expressed an interest in opening a branch of his bank in Birmingham.

Rather than letting an outsider establish a bank, Pettiford and the local black leaders, including J. O. Diffay, N. B. Smith, T. W. Walker, Peter F. Clarke, B. H. Hudson, and Arthur Harold (A.H.) Parker, for whom a Birmingham city school would be named, decided that they could do a better job.

Bank Opens Doors

To ensure the bank’s success, Pettiford and several other community leaders engaged in a three-month campaign of education, speeches, and advertising. The Alabama Penny Savings company opened its doors on October 15, 1890, with Pettiford as its president. It received on deposit that day $555, which, along with the $2,000 already paid in from the sale of stock, constituted its working capital.

The bank was not incorporated until 1895, when it finally accumulated the $25,000 in cash assets that was required under Alabama laws of the 1890s.

Educator Washington said this about the institution in an address given in Birmingham on January 1, 1900:

“I wish to congratulate you among other things upon the excellent and far reaching work that has been done in Birmingham and vicinity through the wide and helpful influence of the Alabama Penny Savings Bank. Few organizations of any description in this country among our people have helped us more, not only in cultivating the habit of saving, but in bringing to us the confidence and respect of the white race. […] The people who save money, who make themselves intelligent, and live moral lives, are the ones who are going to control the destinies of the country.”

Because of its success in Birmingham, officials of the Penny Bank later established branches in Selma, Anniston, and Montgomery. Although the bank achieved success, some African Americans distrusted black-operated banks because of the failure of the Freedmen’s Bureau Bank in 1873.

Like Washington, Pettiford believed in self-help and racial solidarity. Because he also agreed with Washington’s emphasis on developing partnerships with powerful whites, Pettiford established working relationships with white bankers. He obtained assistance from Birmingham’s white financial institutions to train his workers in bookkeeping and banking procedures.

Administrative help from the Steiner Brothers Bank appears to have been the major factor in the Penny Bank’s ability to survive the economic crisis of 1893, when even some white banks failed.

As a member of Booker T. Washington’s Business League, Pettiford helped organize the National Negro Banker’s Association in 1906 and served as its president until his death. The organization’s stated purpose was to foster and encourage the establishment of black-owned banks and support those already in existence. Pettiford travelled throughout the South to assist in the establishment of black banks and became the nation’s leading figure in the African American bank movement.

Under Pettiford’s management, the Penny Bank continued to grow. On July 15, 1902, the deposits were $78,124.21; by October 1911, they had reached $421,596.51. Much of the bank’s success resulted from Pettiford’s and the directors’ emphasis on homeownership.

Records show that the Penny Bank was the leading mortgager to persons buying homes in Smithfield, the most prominent black community in Birmingham. In addition, during the bank’s first decade, Pettiford and other officials engineered many real estate transactions that proved highly lucrative for the bank.

Self-Help

In 1913, the Penny Bank constructed its own building on Eighteenth Street in Birmingham’s thriving business district. The five-story building housed other black businesses on its upper floors. Of its 64 rooms, businesses occupied all except one, paying a total of $8,000 in rent to the Penny Savings Bank. The building represented a tangible demonstration of the director’s philosophy of self-help and economic solidarity: African Americans cooperating to assist other African Americans.

By the time of Pettiford’s death in 1914, the Alabama Penny Savings Bank was the largest and strongest African American owned bank in the United States, doing business in excess of $500,000. In 1915, the bank merged with another black-owned bank, Prudential Savings, and became the Alabama Penny-Prudential Savings Bank, with J. O. Diffay as acting president.

Despite the Penny Bank’s success and its merger, the institution failed in 1915, less than one year after Pettiford’s death. The likely reason for its failure was the absence of Pettiford, who had nurtured a unique relationship with the larger banks, and during times of financial crisis no one could convince these financial institutions to lend assistance as Pettiford had done in the past.

As a result, the Alabama Penny Savings Bank was forced to liquidate its assets and sell its $150,000 building to the Knights of Pythias for $70,000. Despite its rather short life of 25 years, the Penny Bank contributed in great part to the black ownership of homes, the building of churches and businesses, and teaching many African Americans in the city how to properly manage their financial resources.

This originally appeared in Encyclopedia of Alabama. For more visit http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org. Addition information from www.bhamwiki.com.