By Erica Wright

The Birmingham Times

Zachary Edison, restoration technician at the Southern Museum of Flight (SMOF) in Birmingham, doesn’t rewrite history—he restores it.

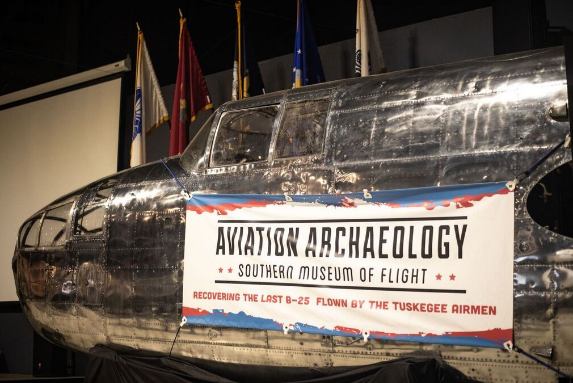

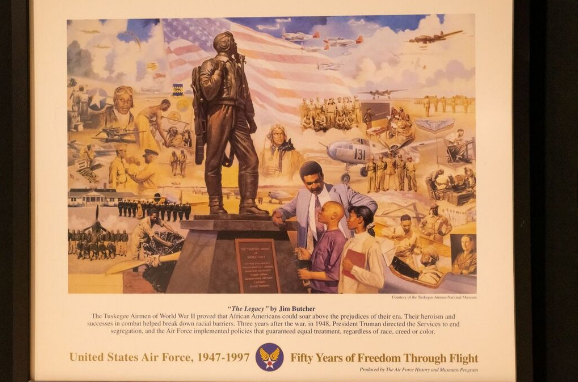

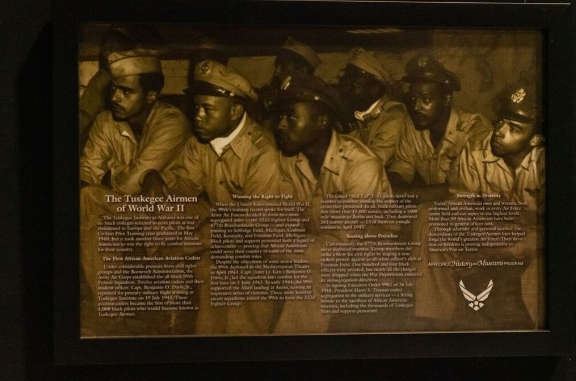

One of his current projects is refurbishing the B-25 flown by the original Tuskegee Airmen, the first black military aviators in the U.S. Army Air Corps, who fought valiantly in World War II.

“It hadn’t had any upkeep in years, so we’re having to start from scratch, take it all the way back down, [strip] the paint off,” said Edison, of the aircraft the museum acquired five years ago. “Some portions had fabric covering, so we had to buy that and put the new fabric on. It [also had] some sheet metal damage [in need of] repair, so it’s been challenging.”

The project is even more special because Edison, 58, a certified aircraft mechanic and instructor for the past 20 years, was assigned to the 332nd Fighter Group associated with the Tuskegee Airmen.

“Everybody assigned to the 332nd, just like the original guys, is considered Tuskegee Airmen,” he said. “It was a totally different era [for the originals], as opposed to when I was in it, because they fought for Civil Rights and against racism; they broke down barriers. I was a troop commander [in Iraq]. Myself and 11 other guys took care of the big, cargo airplanes, so everything that came onto our compound, came in on our airplanes. We were there for 120 days, recovered 3,000 airplanes, and lived through over 120 attacks during that time.”

To have followed in the footsteps of some of the nation’s most famed and courageous airmen is humbling, said Edison: “I don’t talk about it much, and I don’t like to bring it to attention because a lot of the younger kids don’t understand if I say, ‘Hey, I’m a Tuskegee Airman.’ They look at me confused.

“I’m not trying to overshadow those guys. They did groundbreaking, historic stuff. We [new era Tuskegee Airmen] did great, historic stuff, too, in terms of fighting the war in Iraq. The [originals were] different and great; ours is different in a newer generation.”

Restoration Work

As restoration technician and manager, Edison plays a pivotal role with many of the aircraft SMOF visitors see on display.

“If they already look good, we just put them on display. If not, we get them looking good cosmetically like they were when they were originally flying,” he said. “We’re not a flying museum, but we get the aircrafts to look as good as if they can fly. Some of them actually [still] can fly, we just don’t fly them.”

Restoration of an aircraft depends on several factors, including the type, the age, and the condition it’s in.

“We get some aircraft in great condition, and all we do is wash them and put them on display. With some of them, [restoration] can take as long as three years,” said Edison. “We have to find parts, make parts, put them together, paint them. I’m the only technician here, but we have volunteers with aviation backgrounds, so I will use their expertise. If sheet metal needs to be replaced, I’ll ask the guy that has sheet metal experience to replace it. If engine parts need to be replaced, I’ll ask one of the guys with engine experience to replace it. Some of these aircrafts have wood and fabric on them, so I’ll ask those guys with experience to work on that part.”

More than 20 volunteers help with some of the airplanes inside and outside the SMOF on different days of the week. For example, two or three may come on Tuesday, and another group will come on Wednesday.

Edison even gets to put his associate degree in instructional technology and aerospace maintenance technology to use sometimes by teaching in the restoration shop or working with museum interns during the summer.

“A lot of guests come through, and I take them out to the shop and let them know how stuff is done,” he said. “We also get interns who usually spend a week or two weeks [with us]. I let them know what we do, how we do it, and how it’s all set up as far as aircraft maintenance. I teach about the restoration side and try to stay current with the commercial side, like civilian airplanes that people fly daily.”

Volunteers and interns not only work to restore the aircraft but also work on museum displays, such as making mannequins and display cases in house, as well.

Hands On

Edison grew up in Talladega, Ala., where he attended Lincoln High School and Talladega College where he majored in business administration and was a member of the U.S. Army Reserve. He graduated from Talladega in 1984, a year later joined the U.S. Air Force, and did his basic training at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas.

Becoming an aircraft mechanic was easy for Edison, who had been fixing things since childhood.

“There was tons of room to progress in the military and in the commercial world,” he said. “I used to tinker a lot with stuff and work on cars a lot, so that fixing stuff kind of carried over into fixing airplanes.”

While in the Air Force, Edison was stationed at four different bases, but he had the opportunity to travel the world and work on a variety of planes with deployments in Egypt, Turkey, Ireland, Spain, Dubai, Portugal, Malta, Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Iraq.

“I worked on C-5s, C-141s, C-130s, C-9s, and C-17s, and for five years I was an aircraft maintenance instructor,” he said. “The first aircraft I worked on was the Air Force’s largest aircraft, the C-5.”

Edison was both an aircraft mechanic and instructor during his 24 years in the Air Force. He also earned associate degrees in instructional technology and aerospace maintenance technology, and he got an Airframe and Powerplant (A&P) license so he could continue working on aircrafts after transitioning back into civilian life. He retired from the Air Force in 2008, moved to Birmingham from South Carolina, and began working as an aircraft mechanic at Alabama Aircraft Industries Inc., until it closed in 2011.

“I was passing through here one day and saw the museum, so I went in and asked if they needed a mechanic. They said, ‘Yes’—and I’ve been working here ever since.”

Edison describes his job in one word: “Awesome!”

“I could be working on a not-too-old military aircraft or have the privilege of working on the aircraft one of the original Tuskegee Airmen flew,” he said. “We get airplanes from all over. Some are in great shape, some are in not-so-great shape, some have done unique stuff. We’ve got the fastest manned aircraft in the world, [the Blackbird SR-71], sitting outside; not too many places have that. … We’ve got one of five [Russian MI-24] helicopters on display in the U.S. that you can come and see. It’s just an awesome job.”

The Southern Museum of Flight is open Tuesday through Saturday from 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Admission is $7 for adults; $6 for seniors and students; and free for children 3 years old and younger, as well as active military members and their families. For more information, visit Southern Museum of Flight on Facebook and Instagram and @SMOF1 on Twitter, or call 205-833-8226.