By Barnett Wright

The Birmingham Times

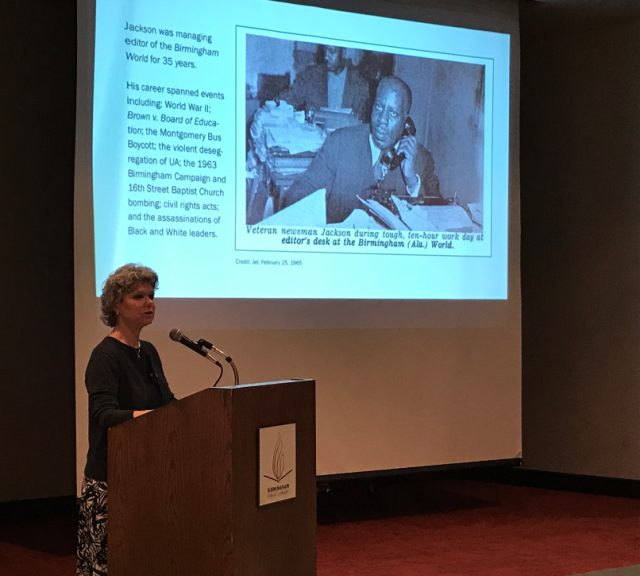

Emory O. Jackson, editor of the Birmingham World newspaper for more than three decades including during the Civil Rights Movement, was a man born for battle and a “roll-up your sleeves kind of journalist” during a crucial period in history, said author Kimberley Mangun, during a lecture in Birmingham on Sunday.

Mangun is author of “Editor Emory O. Jackson, the Birmingham World, and the Fight for Civil Rights in Alabama, 1940–1975,” published in 2019.

She delivered the 17th annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Lecture at the Birmingham Central Library’s Linn-Henley Building co-sponsored by the library and the Birmingham Association of Black Journalists.

Mangun’s research, which took 10 years, revealed an editor who wrote columns as well as editorials for the twice weekly Birmingham World and who delivered hundreds of talks to civic and fraternal groups, NAACP branches, colleges and colleagues, said Mangun, an associate professor of communications at the University of Utah.

“Jackson did some teaching and eventually decided the classroom was just too confining for him,” she told nearly 100 people in attendance Sunday, “the Birmingham World offered him a platform for documenting terrorism and opportunities to advocate civil rights and civil liberties.”

Emory Overton Jackson, a trailblazer and pioneer, dedicated his life to advocating for disenfranchised black people. He wrote on issues including voter registration, poll tax deadlines, NAACP meetings and legal battles against segregated schools, neighborhoods and transportation.

He was a voting rights activist, as well as the founder and first president of the Alabama State Conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) branches.

He wrote stories that had statewide and national impact, Mangun said. For example, he wrote in 1952 about the University of Alabama rejecting Pollie Ann Myers and Autherine Lucy because of their race.

“One thing I found interesting about Jackson is that he continued to advocate for people and issues long after stories had stopped being newsworthy by journalistic standards,” Mangun said. ”For example the UA story essentially ended in 1956 when Lucy finally won her court case, but was subsequently expelled from the university yet Jackson continued to praise her and Myers at speaking engagement and in columns for decades afterwards.”

In many ways, Jackson was a journalist ahead of his time, Mangun said. The crusading editor kept detailed records of officer involved shootings, she said.

“Today websites like MappingPoliceViolence.org and media organizations including the Washington Post compile data on officer involved shootings much as Jackson did beginning in the early 1940s with the limited resources available to him,” Mangun said.

Nothing puts Jackson work into perspective “more powerfully than a stack of 3X5 index cards, three inches high, rediscovered in the recesses in the City Hall basement in 2012 as Birmingham prepared to observe the 50th anniversary of its Civil Rights history,” she said.

“The cards contained the names of the officers who were allegedly involved” in police shootings, she said. “Some mentioned the reason for the shooting such as resisted arrest, or tried to escape, many include the words ‘justifiable shooting,’ ‘justifiable homicide’ or ‘murder.’”

Jackson wrote extensively about violence in Birmingham during the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s when there were 34 bombings plus seven frightening near misses of black owned homes, businesses and churches.

“Jackson decried the violence time and again and he called city office holders to arrest the offenders,” Mangun said. “He also contacted the elected officials and the U.S. Department of Justice to urge them to protect Birmingham’s black citizens ‘from the malicious destruction of property.’”

Jackson and Clarence Mitchell, director of the NAACP’s Washington Bureau, went so far as to meet with the DOJ in 1950.

“Jackson sought a federal investigation into the ongoing violence that was occurring here and in other Alabama cities,” Mangun said. “He submitted information to the deputy attorney general showing that police had killed 52 black men since 1948. Half of the slayings had occurred in Birmingham. Black lives mattered Jackson said again and again, decades before the present-day social movement began.”

Jackson was born in Buena Vista, Ga., and his family relocated to Birmingham, where he was raised with his seven siblings in the Enon Ridge neighborhood on the west side near Birmingham-Southern College. He attended Industrial High School (later named A.H. Parker High School), and in 1928, he enrolled in Atlanta’s Morehouse College, where he was president of the student government and editor of the school’s newspaper, the Maroon Tiger.

Jackson never married and continued to edit the Birmingham World until September 10, 1975, when he died at the age of 67.

Mangun’s book is available for purchase from Peter Lang and Amazon.