By Solomon Crenshaw Jr.

For the Birmingham Times

Jefferson County turns 200 this month, but it gave itself a present in 2018—when the county commission hired renowned Tuskegee, Ala., artist Ronald Scott McDowell to craft a mural to complement the “Old South” and “New South” murals done by John Warner Norton when the courthouse was constructed in 1932.

Norton’s works had raised the ire of many because they depicted a time that had long passed. “Old South” showed a white woman towering over slaves working in a field, while “New South” displayed a white man in a business suit with laborers working in some sort of factory below.

Some thought Norton’s murals should come down, but McDowell wouldn’t have that. He said art should be preserved, so future generations can see what came before their time.

“The reason I agreed to do the new mural was to show a progression,” the artist said. “Jefferson County used to be under the Jim Crow laws of white supremacy. Now we have judges of all different nationalities and races here in Jefferson County.

“I wanted to show that … right in the heart of the mural,” McDowell continued. “I wanted to show that justice is blind, but now it’s blind in the eyes of whites and blacks.”

McDowell’s mural is called “Justice is Blind” and it hangs on a huge panel two stories tall in the cavernous lobby of the downtown Jefferson County Courthouse. It’s between the two older murals painted in the early 1930s when everything, including the courthouse, was segregated. The McDowell mural includes a semi-circle of people wearing judicial robes. Their faces are different hues.

Two hundred years after Jefferson County was formed, it is a different place, a different world as the mural depicts. Gone is the slavery that brought the first blacks to work in agriculture. The county would grow—first from the crossing of rail lines in what would become Birmingham and later as mineral resources fueled a steel industry that allowed the area to blossom.

Change continued as years and decades passed. Steel has given way to medicine and research, as the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) has become the area’s largest employer.

Economic Engine for State

Jefferson County has endured and evolved, having been a key battleground in the fight for Civil Rights in the 1950s and 1960s.

More recently, the county made national headlines after it filed a $4.23 billion municipal bankruptcy in 2011, the largest such filing in the U.S. until it was surpassed in 2013 by Detroit, Mich. The county emerged from bankruptcy in December 2013, following the approval of a plan — in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of Alabama — that wrote off more than $1.4 billion of the debt. Having emerged from bankruptcy, today’s leaders opted not to celebrate the bicentennial with a party.

“We have a tight budget, so we didn’t put any money in for [an official celebration],” Jefferson County Manager Tony Petelos said. “We’ll do some publicity stuff, but we won’t have a party or anything like that.”

Jefferson County, located in the north central part of Alabama and named to honor President Thomas Jefferson, was created by an act of the state legislature on December 13, 1819. The county is home to nearly 660,000 residents, making it Alabama’s most populous county, according to its website. The county is a leader in business, as well.

“The [gross domestic product (GDP)] of Huntsville, Montgomery, and Mobile … does not match the GDP of Jefferson County,” said Commissioner Steve Ammons, who chairs Jefferson County’s economic development committee. “We are still the economic engine of this state.”

Landmarks

Arlington Historic House is a lasting reminder of Jefferson County’s birth. Located on Cotton Avenue, a few blocks west of Center Street, the home was built in Elyton, the first permanent county seat.

“Elyton was a prosperous town, and what made it prosperous was that it was on the Tuscaloosa Highway,” said Carolyn Satterfield, a retired Samford University history professor and member of the Arlington Historical Society. “By highway, we’re talking about a dirt road that went directly to the capitol of Alabama, which was located in the city of Tuscaloosa in the 1840s.

“Elyton had all kinds of things going for it,” she continued. “It was the county seat, which means the legal work for the whole county was done there. It had judges, it had lawyers, it had a little mercantile business.”

Arlington Historic House stands as a monument of Jefferson County’s formative days.

As transportation was the catalyst for Elyton becoming the county seat, transportation also played a role in the county seat moving to Birmingham, the new city to the east. Rail lines came to the area, and those lines crossed in the area that would later earn the moniker “The Magic City” because of the rapid growth it experienced in the early 20th century.

Linda Nelson is executive secretary of the Jefferson County Historical Commission, which was established in 1971, and she smiles at the suggestion that Birmingham “stole” the county seat from Elyton.

“They got voters liquored up,” she said. “They passed out beer or something, whatever whiskey. There were all kinds of skullduggery. It’s pretty well-documented. It’s not an old wives’ tale. It’s true. Birmingham was going to be the county seat.”

Attorney Chriss Doss, a former Jefferson County Commissioner and early member of the Jefferson County Historical Commission, said slavery was present in early Jefferson County cotton production, although not to the extent as other parts of the state.

“The Southern planters and yeoman farmers … provided the fiber, the primary source of the fiber called cotton that was used in so much of the fabric that so many people used,” he said. “Very candidly, the energy that made this production occur was slave labor, and there’s no way to avoid that.”

Industrial Center

After the Civil War, Jefferson County became an industrial center because of the rich mineral resources in and around Birmingham.

“Birmingham was formed in 1871, and the surrounding area—I guess what we would now call the metropolitan area—became industrial in that there rapidly developed a great deal of activity in mining of coal and making coke, [as well as] the mining of iron ore and the smelting of that iron ore to make iron,” Doss said.

Birmingham absorbed several small towns in the area, largely out of a need for cooperation.

“The big thing that brought that about [was] impure drinking water,” Doss said. “It was terrible. It was a health issue. I think these various towns [understood] the significance of survival and addressing in some successful manner the problem of getting clean water.”

That caused those surrounding cities to join Birmingham.

“It became a large city, the Magic City,” he said. “At the turn of the last century, Birmingham often vied with Atlanta, which was a much older city as far as population and all of that was concerned.”

The industrial boom brought a large influx of blacks to the area, and Doss recounts there having been “very strenuous and … inhumane segregation.”

Making Strides

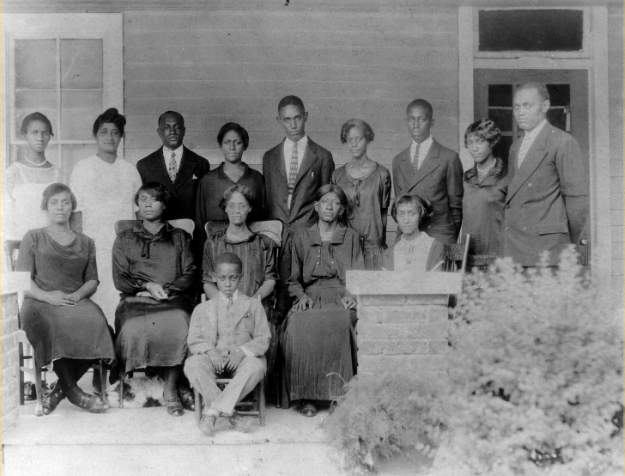

Wilson Fallin Jr., a history professor at the University of Montevallo, said blacks made strides in Jefferson County even before the Civil Rights movement.

“A middle-class black community developed,” he said. “These were people who serviced common blacks—teachers, doctors, lawyers. It was a small middle-class community, along with those who worked in industry.”

The Fourth Avenue Business District became a center of business activity for Birmingham’s black residents. Fallin noted one of the most significant figures in Birmingham in the early 20th century, a pastor of 16th Street Baptist Church named W.R. Pettiford.

“He formed a bank here in Birmingham, the Alabama Penny Bank,” the Montevallo professor said. “That bank became the key financial institution for blacks. Building churches? They’d borrow money from the Penny Bank.”

Jefferson County Today

Today’s Jefferson County is vastly different from the one documented in history books.

The world comes to the area when the Birmingham metro area hosts The World Games 2021, and Bessemer is soon to be home to an Amazon fulfillment center. The county also is on the verge of emerging from a consent decree that was established in 1982, after plaintiffs sued alleging that the county and other defendants had been discriminating based on race and sex with respect to employment.

Other changes from the county’s segregated past are evident, too. Walter Gonsoulin was recently named the first permanent African American superintendent of the Jefferson County School System, continuing a trend that began with the elections of the county’s first black district attorney in Danny Carr and first black sheriff in Mark Pettway in 2017. In addition, the county is stepping away from the day-to-day management of indigent health care, partnering with UAB to form a university health care authority.

And Birmingham, which made headlines around the world with dogs and firehoses being turned on young protest marchers in Kelly Ingram Park during the turbulent 1960s, makes headlines of a different sort with the popularity of Railroad Park.

County Commission President Jimmie Stephens said change in the county has been transformative, from the rise and fall of the iron and steel industries to the rise of medicine and technology in the local economy. He also cited social changes that have replaced segregation with cooperation.

“I grew up in segregation and experienced the Civil Rights movement and the Civil Rights transformation, from where we were separated to where we’re together,” Stephens said. “We really don’t talk about that as much as we should—how we work together and communicate together. We work together much more now than we ever had.”

County Commissioner Lashunda Scales said more still needs to be done.

“Jefferson County has moved [forward] somewhat, but I believe we have a long road ahead of us,” she said. “I think diversity is still somewhat of an issue that we have to overcome. As the county changes and evolves, I believe our practices, the ways we do business and govern need to reflect the same.”

Click here to read more stories celebrating Jefferson County’s bicentennial.