By UAB Medicine News

People who visit or work in the Whitaker Clinic of UAB Hospital likely have crossed paths with UAB Medicine Guest and Hospitality Services representative Henry Brown. He’s usually at the second-floor information desk or the first-floor guard station, always ready to assist patients and quick with a smile and a greeting.

Brown, 76, joined UAB Medicine five years ago as his “post-career” career. The Alabama Power Company retiree and U.S. Army veteran says his earlier work as an electrician ran “neck and neck” with his service in both the Alabama National Guard and the U.S. Army Reserve. Considering his remarkable experiences, you could say that Brown’s entire life has run neck and neck with major events in American and Birmingham history.

Early start

As far as preparing for careers and life in general, Brown says his father was responsible for an early start.

“My electrical training started with my dad when I was only 12 years old,” Brown says. “Dad was one of the first licensed black electrical contractors in Birmingham. He, Sam Carter and Pop Foster were the only black contractors in the city during that time. Dad made me learn the trade. He had three sons from an earlier marriage, and we all became electricians. He knew that a black man in Alabama needed a trade or some kind of skill if he wanted to have regular employment. Dad gave me the first tools I had: pliers, cutters, two screwdrivers and an electrician’s knife. I still have them set aside now in their own box.”

It would be several years before Brown began his career as an electrician, since – as he puts it – “adult life had to start first.”

Activism

“It’s fair to say that my adult life began with the civil rights movement,” Brown says. “I was 19 years old in the spring of 1963. I would march with Dr. King when I could. I was involved in sit-ins at various lunch counters, which was part of our protest efforts. I’m not sure exactly how many times I was arrested. It would all happen very quickly back then. You get arrested and then the next morning someone from the movement gets you out. You’d get cleaned up and they would send you somewhere else for a while. The last time I was arrested, I was taken to the Birmingham City Jail on Sixth Avenue South.”

Brown was at the jail with many other civil rights demonstrators. Earlier during the 1963 Birmingham campaign of the civil rights movement, a peaceful protest tactic coordinated by the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) was devised to crowd jails, detention centers and municipal buildings.

As the campaign continued that year, SCLC leader James Bevel initiated what became known as the Children’s Crusade, which he and other leaders believed might draw the nation’s attention to Birmingham. In May 1963, thousands of students marched throughout the city to peacefully protest segregation, but they were met near Kelly Ingram Park by police, who used dogs and fire hoses to turn back the march. It was a key moment in the civil rights movement.

Brown recalls being hit with water from the hoses, as well as other risky experiences later that summer. His mother didn’t want him involved in the marches.

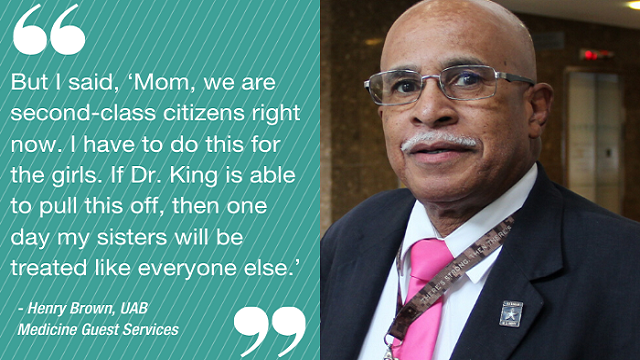

“I was the second-oldest; I had three sisters. I was her only son, and Mom knew the dangers of the marches and demonstrations,” Brown says. “But I said, ‘Mom, we are second-class citizens right now. I have to do this for the girls. If Dr. King is able to pull this off, then one day my sisters will be treated like everyone else.’ So it was something I needed to do, but I would be lying if I said I wasn’t scared, too. I knew who Bull Connor was (Birmingham commissioner of public safety at the time). Or, it’s more accurate to say that, before that summer, I only knew of him. My dad had done electrical work in his house.”

First encounter with UAB

By the time Brown reached the jail after his last arrest, he already had a more serious problem – one that would make his first connection with UAB Hospital.

“I had taken ill that day, never felt so bad in my life,” Brown recalls. “I kept telling the officers I was in severe pain, but they didn’t believe me. But my state of illness must have been obvious when they took me out into the yard for exercise. They knew I needed medical attention at that point, so some officers put me in a squad car, handcuffed me to the door, then drove me to the emergency room.”

The police took Brown to the Hillman Emergency Clinic at what then was known as University Hospital. At the time, African-American patients were treated there, while white emergency patients were treated in another part of the hospital. That arrangement often caused a shortage of staff and resources. Patients sometimes waited an hour or longer for care.

“The physician who saw me was a young guy,” Brown says. “I can picture his face even now, but I don’t remember many details of that time in the ER. But I certainly recall a thorough examination and then the doctor saying, ‘Young man, you have acute appendicitis.’ The nurse asked him if we were going to surgery, and the doctor said there wasn’t even time to transfer me to another area of the hospital. They operated on me right there in that old emergency room. I learned later that as soon as the incision was made, my appendix burst. So that doctor made a lifesaving decision.”

Surprise intervention

Another surprise awaited Brown as he recuperated from surgery.

“I was handcuffed to the bed during my recovery,” Brown says. “There was an officer there with a dog standing guard, so it was clear I was still going to jail after I recuperated. But one morning, Rev. A.D. King, who was Dr. King’s younger brother, and Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, a co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, came to the hospital, had me released and then took me home to finish recuperating. I had marched with both of them, but I was sure surprised to see them coming to get me at the hospital.”

A few years after his time in the movement, Brown was drafted into the U.S. Army. Upon being discharged after two years, Brown joined the Alabama National Guard and later began working for Alabama Power. In 1991, a coworker persuaded Brown to join the U.S. Army Reserve. A decade after that, another major event shaped Brown’s career path: Sept. 11, 2001.

Duty called again

“I was working for Alabama Power at Miller Steam Plant when I got the call to active duty at 2:20 that afternoon,” Brown remembers of that infamous Tuesday in 2001. “My boss had called me on the radio and asked if I was still working on the motor I was repairing. He said there was some paperwork for me in his office and I needed to stop the job I was doing and see him. At that moment I was only concerned that he probably had another work order that would interfere with plans my wife and I had that night. But it was an order to contact my reserve unit, which had just been activated that morning. I had eight hours to call my commanding officer and get my bags packed. I was 58 years old at that time.”

For the next three-and-a-half years, Brown was on active duty at various locations throughout the country. For security reasons, he can’t divulge every posting, but his unit was deployed to the Pentagon at one point. The members were among numerous Army Reserve soldiers and units responding in their civilian capacities to support rescue and recovery operations and secure federal facilities across the nation immediately after the 9/11 attacks. Many of these same reservists went on to prepare soldiers for deployment and operations in Afghanistan that began a month later. Brown rose from corporal to the rank of sergeant first class while serving in his reserve unit. He was injured and received two commendations for what he refers to as a “little scratch,” but he offers no other details.

Keeping busy

“That was my first training on computers,” Brown says. “Anything the soldiers needed, I would order: boots, ammunition, the whole works. While I was recuperating from my injury, I was diagnosed with prostate cancer. The surgery was successful; I’m a 17-year cancer survivor. During that recovery, my military mandatory retirement date came up, so I was discharged and went back to work for Alabama Power. When I retired from there, I began looking for some part-time work. I started with a parking company that had a contract with UAB, and when their contract ended, I went to Princeton Baptist Medical Center. While I was at Princeton I got a call from UAB Medicine with an offer for the job I now have with Guest Services. I was elated. UAB has been very good to me.”

Brown is a 60-year member of Sixth Avenue Baptist Church and sings in the male chorus. He says his wife of 30 years, Juanita, is his best friend and keeps him grounded, along with his commitment to staying busy.

“If you retire and don’t find some kind of work or activity, you may wind up sitting at home getting weak and sick,” Brown says. “I’ve been getting up early and working long hours since I was young, so I guess I’m afraid to stop doing what got me here.”