By Sherrel Wheeler Stewart

For the Birmingham Times

Three years ago, Nathaniel A. Barrett Elementary School had the kind of grades you wouldn’t want to show to anyone. It received a grade of F on the annual Alabama Department of Education school report card on academics, with an overall score of 47 on the state’s measure of progress and achievement.

The 118-year-old rustic brick school in the heart of East Lake was among the worst in Birmingham. Records show that students often were absent from school and less than 10 percent were reading at grade level.

But now achievement is surging at Barrett. The school received a C on its most recent school report card—an increase of 35 percent over the past three years.

School leaders, including Barrett Principal Tikki Hines and Birmingham City Schools (BCS) Superintendent Lisa Herring, celebrate the school’s success, but they also recognize there’s more to do at Barrett and the system’s other 41 schools.

“There is an expectation of excellence. That is our goal at Barrett Elementary,” Hines said. “The students know it, and the instructional staff embraces it.”

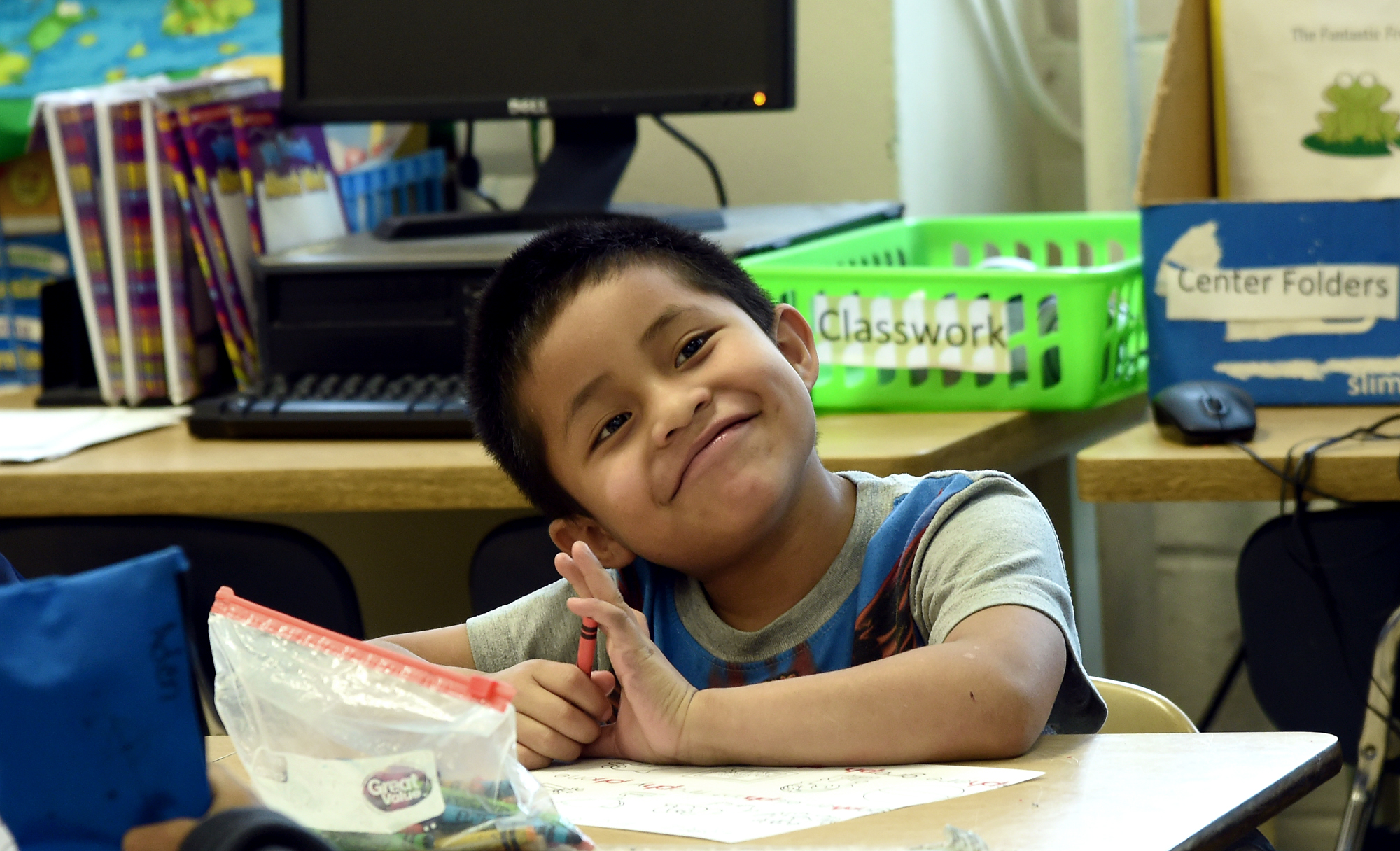

Barrett’s students come from diverse backgrounds: about 8 percent are Hispanic, including 5 percent who speak English as a second language (ESL); and more than 80 percent of its 435 students are economically disadvantaged, according to the Alabama State Board of Education.

First Steps

When students come through the doors of Barrett, Hines and the staff make sure parents and children know they are important to the school’s mission of teaching and learning. One of the first steps toward helping students learn is removing distracting barriers.

“If there is an obstacle, I want to address it to make sure instruction is still taking place,” said Hines, who has been principal at Barrett for a year and half. That can be a struggle because children are bringing their burdens to school. I have some children whose parents are in prison, or they’re struggling with the loss of a parent and other disruptions in their home life. Is learning really a priority when you have personal struggles?”

“Children often come to school broken. We have to love them, fix them, and teach them at the same time,” Hines added.

Sometimes, it doesn’t take much to remove a barrier. After being assigned to Barrett as interim principal in 2017, Hines noticed that some children came to school with dirty clothes and struggled with low self-esteem and a lack of confidence. Someone donated a washer and dryer to the school, and the staff worked together to set up a student-clothing closet.

Hines recalled, “We had one little girl who wore dirty clothes, but she also wore lip gloss. So, I said to her, ‘You want to be cute. I want to help.’”

After the little girl’s clothes were washed, Hines told her, “Now you don’t have to worry about how you look.”

Sometimes, there’s a barrier that prevents students from getting to school every day. Hines has been known to pick up students, if that’s what it takes to consistently get them to school.

In 2017, almost a third of Barrett’s students had 15 or more absences for the school year; that’s the level the state considers as chronic absentee. In the last report, only 9 percent of the school’s 435 students had 15 or more absences—and now Barrett’s absentee rate is among the lowest in the city.

Hines said parents and students respond when she and the teachers use a personal touch and encouragement. They will call a student who was absent and say, “We missed you,” Hines said.

“It means something when you call them and they know they can also call you,” she added. “It’s about having that conversation.”

In some classes, students even have an attendance tracker in a folder. They color each day on the tracker to indicate their attendance. Teachers said this helps to reinforce the importance of regularly attending school and being on time.

Increasing school attendance has been a priority throughout BCS, said Superintendent Herring.

“Strong attendance starts with strong parental and family engagement,” she said. “When parents and families are engaged with the education of their children, scholars are at school every day, in class, on time, and ready to learn. When scholars are at school, scholars are learning.”

Parental and Community Participation

Getting children off to school is not a problem for Talethia Parrish-Allen, the mother of two Barrett students.

“My children look forward to going to school every day,” she said, adding that the reason for her children’s enthusiasm is their teachers and the principal.

“They take the job seriously at Barrett. They’re not just there for the paycheck. They treat the children like they really care.”

The connection with the school and the staff at Barrett, especially recently, has made a difference for Parrish-Allen and her family. She’s in touch with the school regularly through an app on her phone, and when she needs to have an actual conversation, she has cell phone numbers for her children’s teachers. The full-time mom is also a regular visitor at the school.

Hines said she’d like to have more parents participating regularly at the school. Though Barrett does not have an active PTA, it does have lots of volunteers from community groups, such as Better Basics, a United Way of Central Alabama Inc. program that provides literacy intervention and enrichment programs for elementary- and middle-school students throughout the state. The school also employs regular tutors to support struggling students.

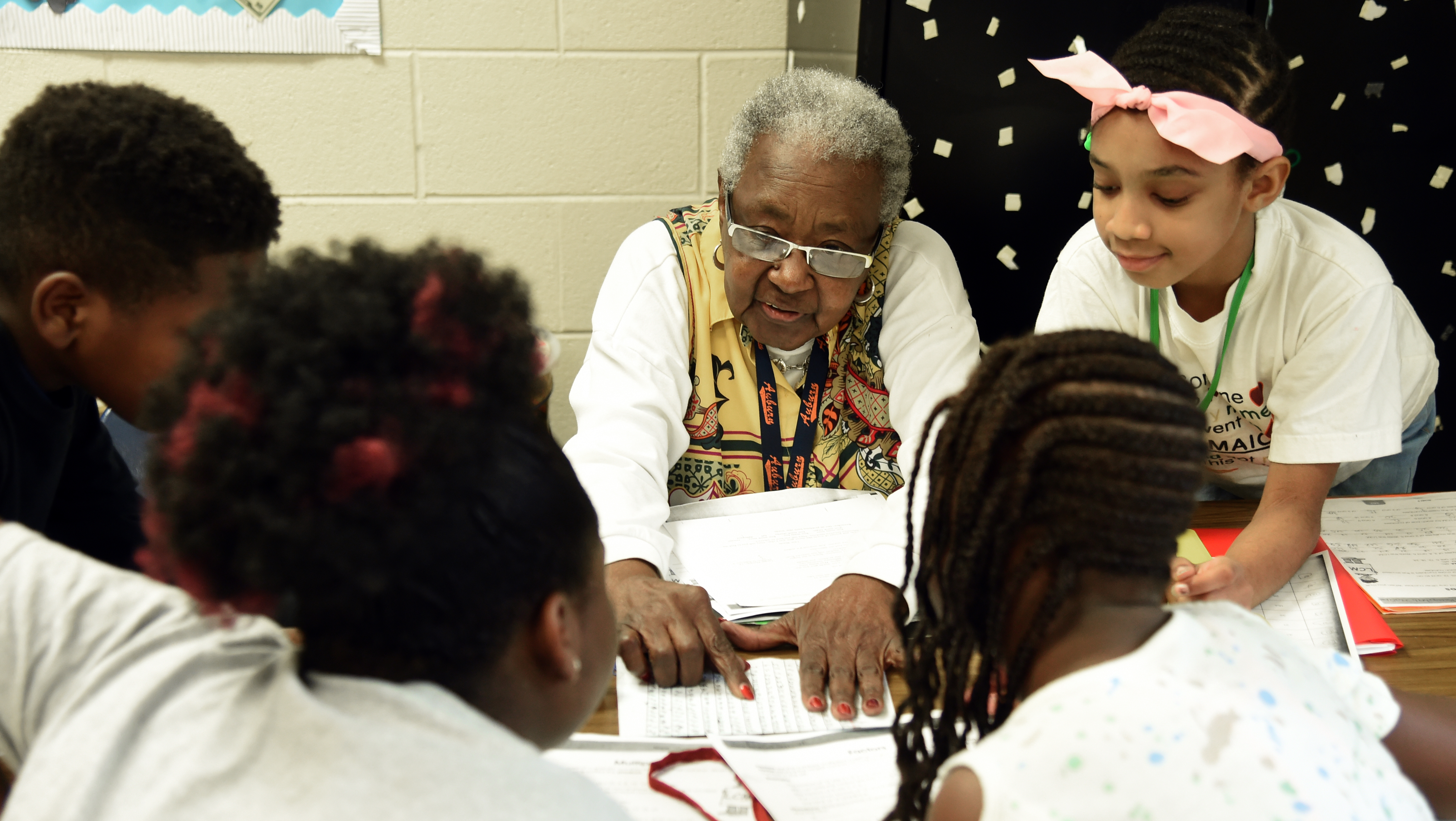

Gladys Williams, a veteran teacher who retired from Homewood City Schools about 20 years ago, often tutors fifth-grade classes; she specializes in math and language arts.

“I go in and try to get the students to focus. I’m able to give them some of that much needed one-on-one attention,” said Williams, adding that Barrett’s students could be even more successful with more help from volunteers.

“We need to see more African American volunteers in the school,” she said. “It’s a good environment for learning, but they need more help.”

Subject Matter

One of the largest gains for Barrett students has been in math, a subject in which one-fourth of the students are now proficient or above grade level. Just a couple of years ago, only 15 percent of Barrett’s students were proficient or more in math, according to state reports.

Hines said math is one of her favorite subjects, and the school took some intentional steps to help students better understand and master math.

“We looked at the data, and that showed us what students did not know,” said Hines, adding that she also looked at instructional time for math.

“I’m a math person,” she said. “When I came in [as principal of Barrett], I said, ‘We have to have more math instruction time.’”

That meant teachers needed to set benchmarks for achievement for each student and establish a calendar to serve as a pacing guide to carry them through the year.

“We can’t get stuck on division for three months,” Hines said.

In addition to these steps, teachers have built time for collaboration into their weekly schedules.

“I encourage teachers to share their best practices and to work together,” said the principal.

She encourages teachers on each grade level to collaborate but also likes to see that collaboration across grade lines. For example, Barrett’s first-grade classes are near a couple of third-grade classes on the first floor of the building. This setup is intentional, Hines said. Those classes are close so teachers can easily discuss the expectations as students progress through school.

Joyce Stallworth, a former professor and administrator at the University of Alabama who travels around the world teaching educators how to help boost student achievement, said collaboration is the key to success.

“There is no such thing as 10 steps for turning a school around,” she said. “Each school, each situation is different, but it usually starts with a sincere commitment and collaboration.”

There has to be buy-in from the school district, the principal, and the teachers, Stallworth explained: “They have to say, ‘We’re going to visit each other’s classrooms and share instructional feedback. We’re all going to do what works.’”

Stallworth calls this approach “shared problem solving.”

“Teachers understand how to improve themselves. That’s an important piece of the total effort,” she said.

The Student’s Role

From day one, children at Barrett Elementary School learn that they play a major role in what they learn and how they learn. When test results come in, for instance, students are taught what those results mean.

“I will talk with a fifth grader and explain, ‘You’re in the fifth grade, but this score shows that you are reading on the level of a second grader. What are we going to do about that?’ I tell them, ‘This is where you are, but I know you can do better,” Hines said. “I believe in holding students responsible for their learning, and that’s important.”

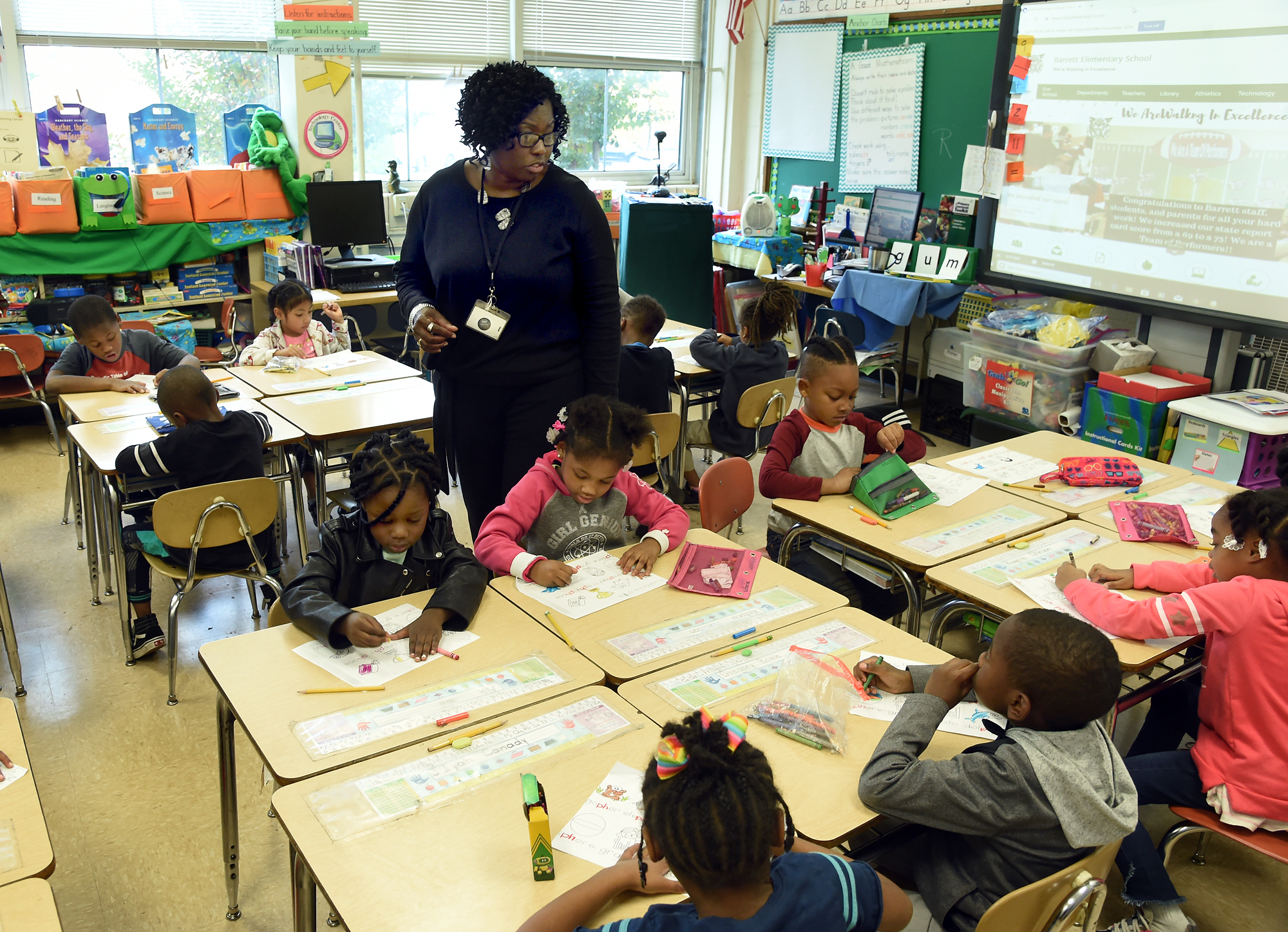

Teachers also place heavy emphasis on student participation.

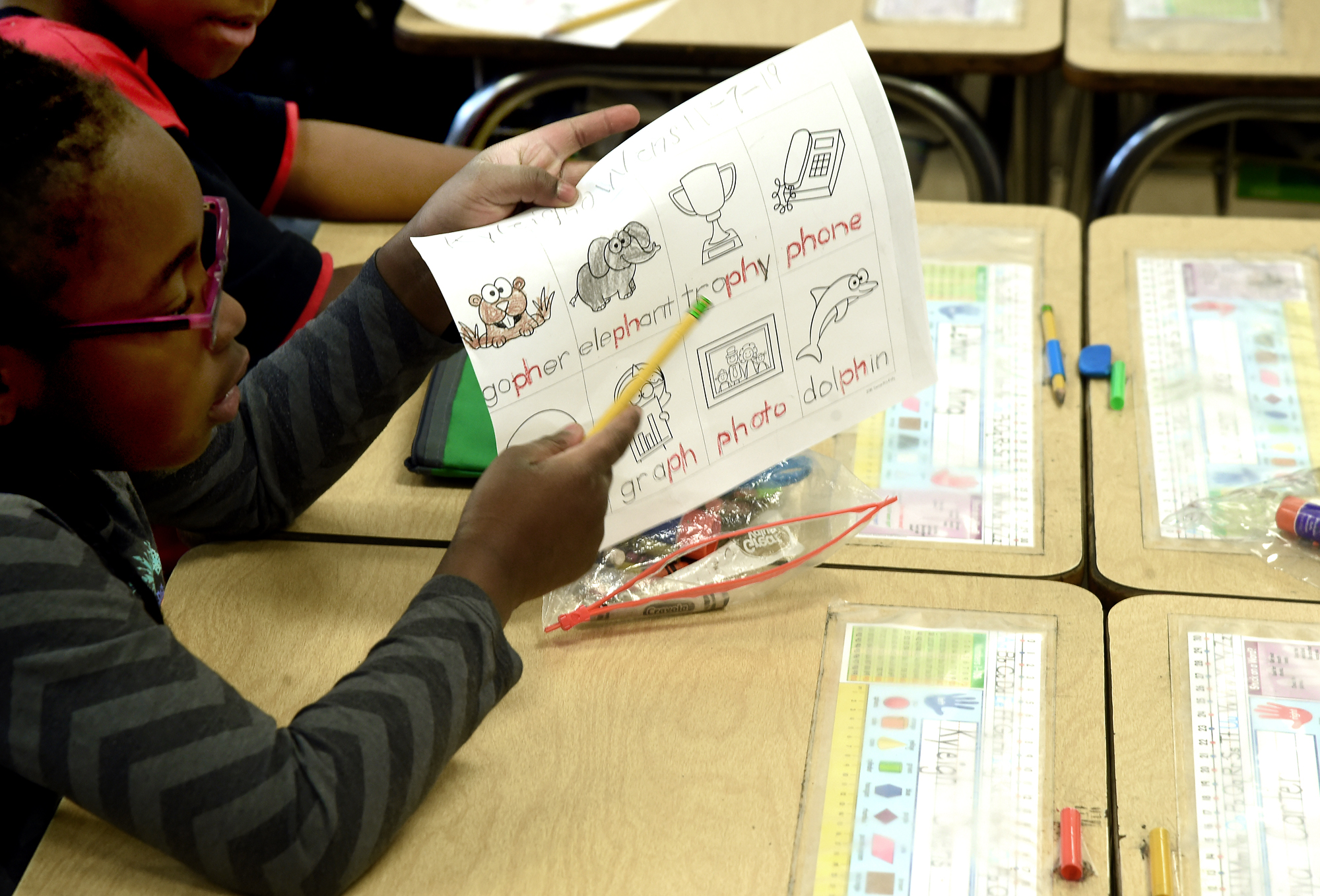

In Yolanda Ross’s first-grade classroom, a big, white smartboard is front and center. It’s connected to the internet, so she can use it show interactive videos that support class lessons. It also can be used in a chalkboard fashion, allowing students to go to the board to solve problems or draw illustrations.

During a recent class, Ross walked around her room carrying a little bucket filled with cards on which each student’s name was written. She pulled out a card, read a name, and called that student to answer the question. If the answer was incorrect, Ross simply pulled another card and said, “Let’s all help out.”

Ross has been a Barrett teacher for 20 years and has even taught the children of some of her earlier students. She believes the school’s nurturing environment will help propel students further.

“I’ve been blessed to be right here,” she said. “A lot of the children now are reading when they come here.”

Click here to read more stories about progress in Birmingham City Schools.