By Chuck Chandler

Alabama Newscenter

Six years after Gov. George C. Wallace made his infamous stand in the schoolhouse door to keep blacks from attending the University of Alabama, Wilbur Jackson received a scholarship to play football with the all-white Crimson Tide.

Nearly a half-century later, Jackson downplays his role in history, preferring to point out the good things that came from his breaking the color barrier. He made lifelong friends in Tuscaloosa and still admires Pat Dye, the former UA assistant coach who recruited him despite Jackson having played just 14 games in high school. And Jackson still reveres Alabama’s legendary head coach.

“He taught me life-altering lessons,” Jackson says. “There will never be another one like him. Some may win more games, some may win more titles, but they’ll never be better than coach (“Bear”) Bryant.”

Jackson admits he “almost quit a lot of times” after arriving on the college campus. He had gotten a taste of things to come when the all-black D.A. Smith High School in Ozark was closed and the students transferred to the majority-white Carroll High School.

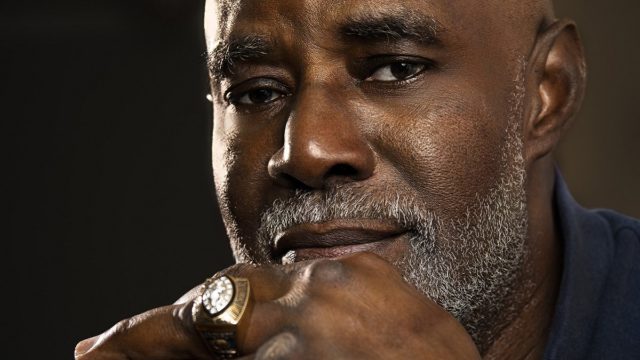

“It wasn’t that bad because all the kids I’d been with from the first grade on went with me to Carroll. There was a comfort level,” says the 67-year-old Jackson, relaxing in his home in Ozark.

At D.A. Smith, Jackson played basketball from the eighth grade through the year the school closed. He played baseball two years but gave up the sport after breaking a leg. He was enticed into football his junior year, playing mostly running back. During a game, quarterback George Williams suggested to the coach that his speedy friend get a shot at wide receiver.

“Coach said just run long and, George, you throw it to him,” Jackson says. “It turned out to be a touchdown. Ever since then, George says ‘I made you,’ every time I see him.”

Dye recruited the Wiregrass for the Tide. He had signed Ellis Beck and Dexter Wood from Carroll High in 1968, so he was familiar with coach Tom McLendon. The Eagles’ coach, an Auburn alumnus, showed Dye film of Jackson from the 1969 preseason jamboree. The Tide eventually signed Jackson as a wide receiver. Despite switching to running back at Alabama, Jackson would continue wearing the jersey number 80 throughout his career.

“Years later, I asked coach McLendon, ‘Why did you suggest to coach Dye that I go to Alabama,” says Jackson, who was a pallbearer for his high school mentor. “He said, ‘I just thought it would be better for you.’”

During the 1960s, Auburn was averaging six wins per season, while Alabama was averaging nine wins each year and was named national champion three times.

Talking To The Bear

Jackson had thought little about either program, since neither had ever had a black player. But Dye met Jackson after Carroll played Montgomery’s Lee High School to open the 1969 season. Dye began phoning Jackson frequently and received updates about each game performance from The Southern Star editor Joe Adams. Jackson would visit Tuscaloosa twice before signing. He talked to Bryant for the first time on Sept. 27 after the Tide beat Southern Miss 63-14.

Jackson says the reluctance of college football coaches in the South to recruit black players 50 years ago “was just the times. Old habits died hard.” He says Bryant was among “a few good men and women who had the courage” to integrate.

Freshmen athletes didn’t play varsity football during Jackson’s time at Alabama, so his college career didn’t start until 1971, when he was one of two blacks on the team (along with tight end Randy Moore). The Tide went 11-1 his sophomore season, losing the Orange Bowl to Nebraska and missing out on a national championship.

His junior year, Jackson was one of eight blacks on the team that went 10-2, losing the last two games: 17-16 to Auburn in the famous blocked punts affair, and 17-13 to Texas in the Cotton Bowl. In 1973, Jackson was one of 14 blacks playing for the Tide team that won 11 straight before losing in the Sugar Bowl to Notre Dame after the Coaches Poll had already declared Alabama the national champion. Jackson says it was the toughest loss of his football career.

“That one hurt,” he says. “I didn’t get over that until we beat them in the (2012) national championship, 40 years later.”

By the season the Tide made up for Jackson’s worst memory, black players composed 70 percent of the University of Alabama’s football roster.

Drafted In The First Round

Jackson, who still holds the Tide record for yards per carry (7.2), was drafted in the first NFL round by the San Francisco 49ers in 1974. Players made little compared to signing salaries today, but it was new financial territory for the son of a career railroad man.

“We never were rich, but we had everything we needed growing up,” he says. “When I signed that contract, it was more money than I’d ever seen. Everyone around town started thinking I was loaded. My whole thing became saving as much money as I possibly could.”

Jackson played five seasons with the 49ers, but had continuing leg problems that might have originated in the College All-American Game in Texas after his senior year, which kept him from playing in the College All-Star Game in Chicago, he told Adams during a visit to Ozark. His right knee was badly injured three times in the pros, and Jackson says it still aches.

The NFL was a dream scenario for Jackson, playing on the same field with his heroes, looking across the sidelines to see the likes of future Hall of Fame coaches Tom Landry and Hank Stram.

However, Jackson’s most fond memories of professional football aren’t his on-field performances, but of the times other Crimson Tide alumni took the time to talk. Leroy Jordan, Kenny Stabler, E.J. Junior, Johnny Davis and many others greeted him before and after games.

“They wanted to make themselves known to me. It was all because of the connection to Alabama and coach Bryant,” he says. “Those things stick in my mind and will probably be with me forever.”

Jackson spent his last three years in the NFL with the Washington Redskins. He closed out his football career in Super Bowl XVII, winning a World Championship ring. However, he played the game with a heavy heart.

“I was getting dressed for practice when (future Hall of Fame coach) Joe Gibbs came up to me and said ‘A bunch of reporters are going to be at your locker,’” Jackson says. “I said, ‘What’s wrong?’ He said, ‘Coach Bryant passed away.’”

Back Home

Unlike many prominent athletes, Jackson returned to his hometown at the end of his professional career, opening Three Star Cleaning Service. He ran the business for 30 years until his wife, Martha, became ill six years ago. They’ve been married 39 years and have a daughter, Emily, who lives in Ozark and visits almost every day. Jackson had a heart attack and surgery to implant stents in January but says he’s “feeling good for an old man.”

Jackson says he never wanted to live anywhere except his hometown, where he and his sisters still look out for the house they grew up in. He was disheartened by life in the big city many years ago and is happy to get back to Ozark, where he’s a hero to many people.

“When I was in San Francisco, a guy had passed out on the sidewalk. I was the only person who stopped and helped him; everyone else just walked by,” Jackson says. “I’d never seen that. I knew if I was in Ozark, every person would stop and check on him, or me. I knew I needed to go home.”

This story originally appeared on www.alabamnewscenter.com.