By Erica Wright

The Birmingham Times

As an avid student of race and culture with a passion for telling stories, Majella Chube Hamilton wakes up and goes to sleep with a love for history. That’s why her work as executive director of the Ballard House Project Inc. is so important.

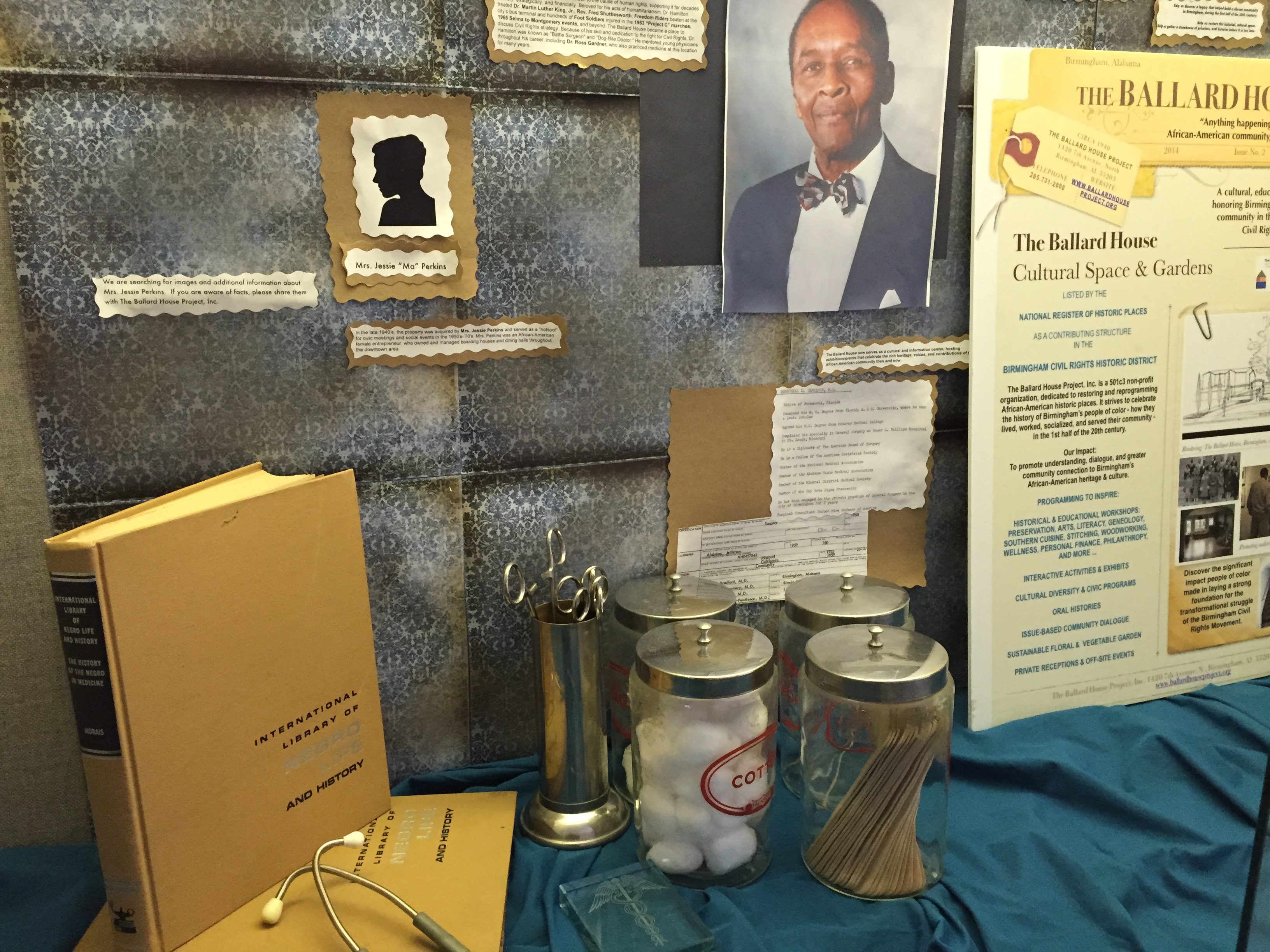

“We research, document, preserve, and share the information we uncover regarding the African American experience in Birmingham,” said Hamilton. “We host oral-history sessions, community conversations, and temporary exhibits, and we’re [also] working on permanent exhibits.”

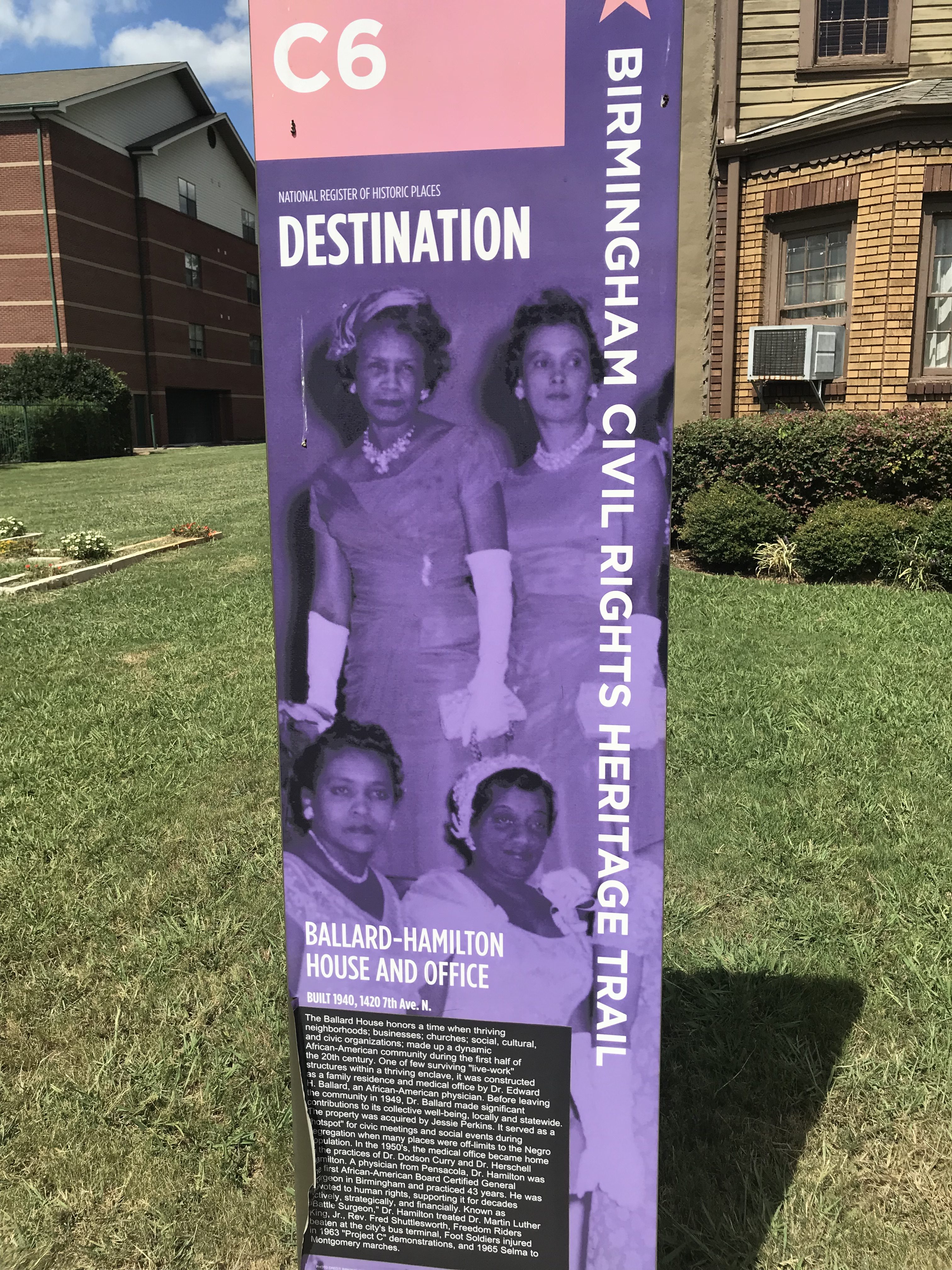

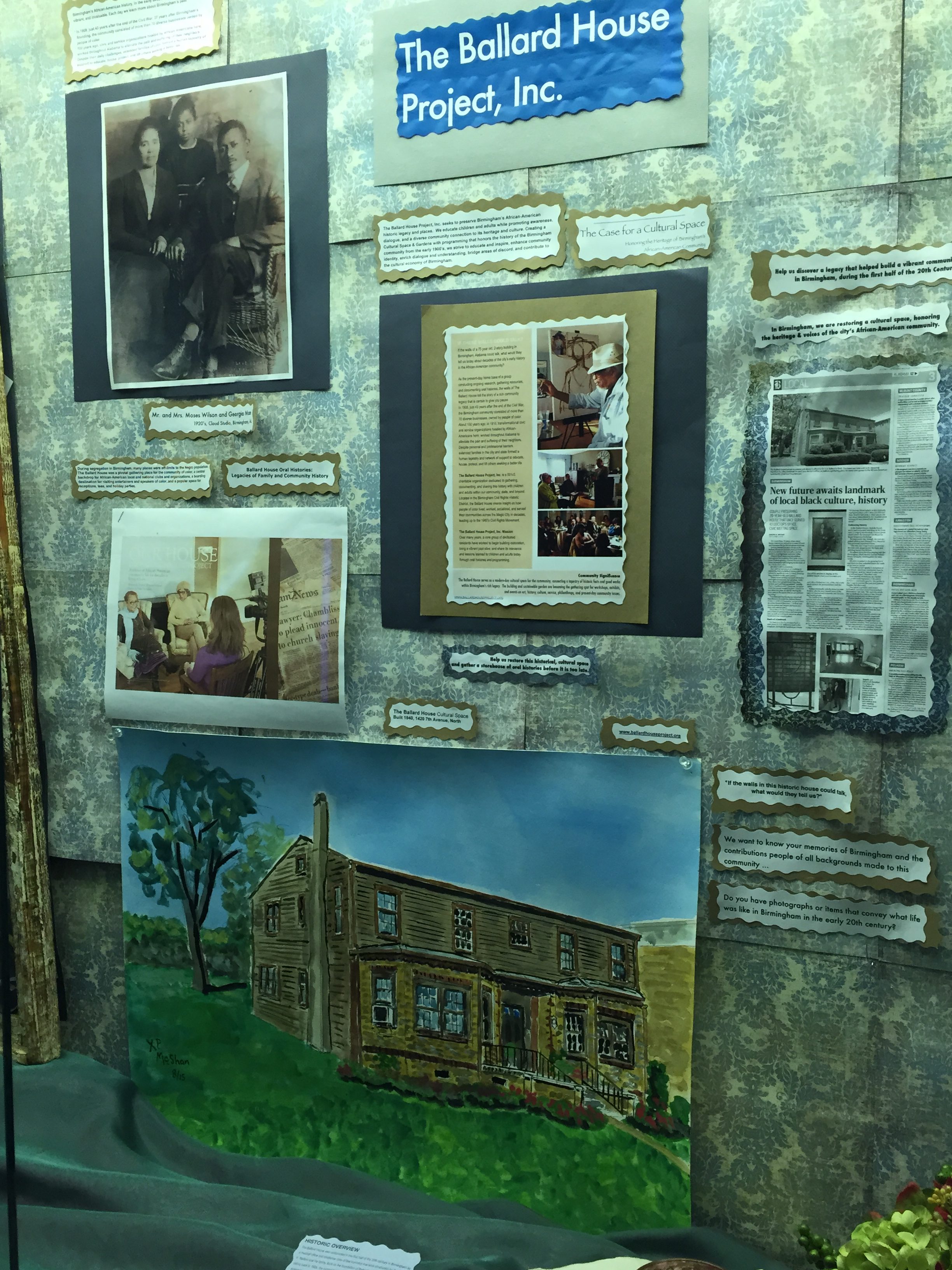

The Ballard House Project Inc., part of the downtown Birmingham Civil Rights District, is a 501(c)(3) charitable organization dedicated to disseminating the history of the African American experience among children and adults within the community, across the state, and beyond.

The building, named after renowned Birmingham physician Edward H. Ballard, MD, was constructed in the first half of the 20th century as a medical office and residence for the doctor’s family; it is one of the few surviving live-work structures in the Magic City.

The Ballard home served as a meeting place for African American organizations barred from gathering in other areas of the city and hosted noted physicians, including Dodson Curry, MD, Herschell Hamilton, MD, and Ross Gardner, MD.

Hamilton and her team focus on and feature not only specifics about what happened in the Ballard House but also the innovative contributions, educators, business owners, and women who lived together and created amazing networks throughout Birmingham.

“We have some resources we’ve gathered that are part of our exhibits, some of which are from the early 1900s,” Hamilton said. “We have information we’ve been sharing about the African American experience in Birmingham, … what was going on here and what we think is important for the community to know.”

Shared Experiences

The Ballard House Project, which received its nonprofit status in 2010, began with community conversations, collective-memory sessions, and oral history.

“We have been working for more than 10 years to gather the shared experiences of [Birmingham’s] African American community. We started having community conversations and gatherings of individuals to learn about their shared experiences and also individual oral histories,” said Hamilton, who has long been interested in learning the back story of a particular initiative or why things are the way they are.

“I recognized early on that there were aspects of this community that had been marginalized, had been ignored, and we weren’t talking about it,” she said. “People talk about their culture and their families and their extended families and their neighborhoods, usually within their own circles. I felt through all of my community activism that some aspects were not being discussed and engaged.

“It’s important to uncover and discover rich, historical information not to dwell on the past but to connect what happened yesterday with what is currently happening in our community today,” Hamilton said.

“In order to move forward, we feel that we’ve got to reach back and find out about what happened in the past so we can empower each other,” she continued. “I’d like to see children, adults, all of us be empowered by this information. … I’d also like to make sure that this is the history of not just Birmingham’s African American communities but all of Birmingham’s communities, which are part of the history of this nation. It is universally important.”

“Culturally Rich”

Hamilton, who is in her early 50s, spent most of her childhood in Franklin, La., a small town outside of New Orleans. When she was 12 years old, her family moved to Gary, Ind.

“My childhood was culturally rich,” she said. “My parents were dedicated to the community in which they lived, and they worked all of their lives to uplift the small community we lived in. I have one brother and two sisters, and we all learned the importance of hard work, giving back to our communities, and using the opportunities we received in ways that would be beneficial for others.”

Both of Hamilton’s parents, O’Neal and Merion, were educators and community activists.

“They were Civil Rights activists in the sense that they broke down barriers in their community, as well as worked to unify their community,” she said. “[In Franklin], there is a street named after my dad and … a library named after my mom. In that community, my mother was the first African American librarian … and my dad was one of the first African American principals.”

When the family moved to Indiana, Hamilton’s parents were retired. They moved so her father could help his brother, who was a family physician, with his medical practice.

Hamilton finished high school in Gary and went on to Howard University in Washington, D.C., where she majored in public relations.

“I did several internships in that career and decided I wanted to stop after three years in school for a period of time to work in D.C.,” she said. “I started an internship and really liked it, so I was like, ‘Hey, this is great. I want to do this.’ I decided to really get my feet wet and see if I really liked what I was doing. I worked for close to year and then I decided to finish my studies at DePaul University in Chicago, [Ill.]”

Hamilton earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in communications with an emphasis on public relations and journalism. While living in Chicago, she worked in several different fields and was engaged to be married to her college sweetheart, Herschell, who she met at Howard. The Hamiltons, who have been married since the early 1990s, have two children, Jillian and Herschell O’Neal, called Neal. Jillian is a Howard University graduate currently pursuing a PhD in psychology at the University of Oregon, and Neal is a student at Howard.

The Magic City

Hamilton accepted a position with Macy’s and took part in the company’s executive training program, which is how she ultimately landed in Birmingham. After living in Atlanta, Ga., she and her husband relocated to the Magic City, where Hamilton moved into a corporate position with the locally based Parisian department store chain (now known as Belk).

“Eventually, I became the public information director for the city of Birmingham and worked for Mayor Richard Arrington and his administration for a little more than five years,” she said. “In that role, I created and opened the Office of Public Information to inform, engage, and be responsive to the questions and needs residents had about their city.”

From there, Hamilton started her own strategic communications business.

“I did project management and worked on a number of different special projects, including editing magazines and conducting special-event initiatives,” she said. “[I also videotaped] projects, managing and coordinating … many that dealt with community, culture, and history.”

Hamilton put her business to the side for a time to work for Southern Living magazine, covering areas such as interior design and architecture. What she enjoyed most, however, was doing features that enabled her to chronicle the stories of prominent African Americans in society.

“I did stories on people like Children’s Defense Fund founder Marian Wright Edelman and the quilters of Gee’s Bend,” she said. “I also did a story on Haley Farms, the farm outside Knoxville, Tenn., that [“Roots” author] Alex Haley purchased prior to his death.”

During her magazine stint, Hamilton was also able to cover the African American experience: “I saw a gap was there,” she said. “[There were so many] individuals and aspects of our community that had contributed so much but not very many people knew about them, so that was an opportunity I loved.”

After leaving Southern Living, Hamilton returned to being a businessowner, establishing Enclave Communication Strategies, where she created strategic plans for projects in the community. She spent her free time on efforts designed to raise awareness about history, art, and culture, and along with her husband and others started working on the Ballard House Project.

“Quietly and methodically, we started to pull back the layers on the Ballard House and began stripping things away and restoring what was here,” said Hamilton, who is currently enrolled in a PhD program in history with an emphasis on race and culture at Howard University.

“We realized how important this aspect of history in the community is to the entire history of the area, so we started making plans to do what we’re doing now—telling those stories and highlighting the voices and experiences of the African American community in Birmingham.”

Talking Circles

This summer, the Ballard House Project started hosting a new series, entitled “Talking Circles: The Impact of Jim Crow Then and Now.”

“We cover every facet of the impact of Jim Crow, [including] culture, health, education, business, housing, voting, traumatic violence, and everything as it relates to race and the laws, customs, and ordinances [under] Jim Crow in Birmingham,” said Hamilton.

“We didn’t know exactly how we were going to focus on it, but it was a wonderful opportunity because we focus on dialogic engagement. Through dialogue [among those attending the Talking Circle], we were able to determine the specific topics or facets of community impact we wanted to focus on. We’re inviting different individuals and community leaders who have some expertise on the different topics … to lead this initiative.”

So far, there have been three Talking Circles at the Ballard House and other locations. They are held on the second and fourth Saturday of each month; starting in October, they will be held on the second and third Saturday of each month. Among the myriad topics discussed are genealogy, migration, and the African diaspora. At the next event, scheduled for October 12, Greg Townsend of the Jefferson County Department of Health will discuss the impact of Jim Crow on health and health care in the African American community.

Ongoing Restoration

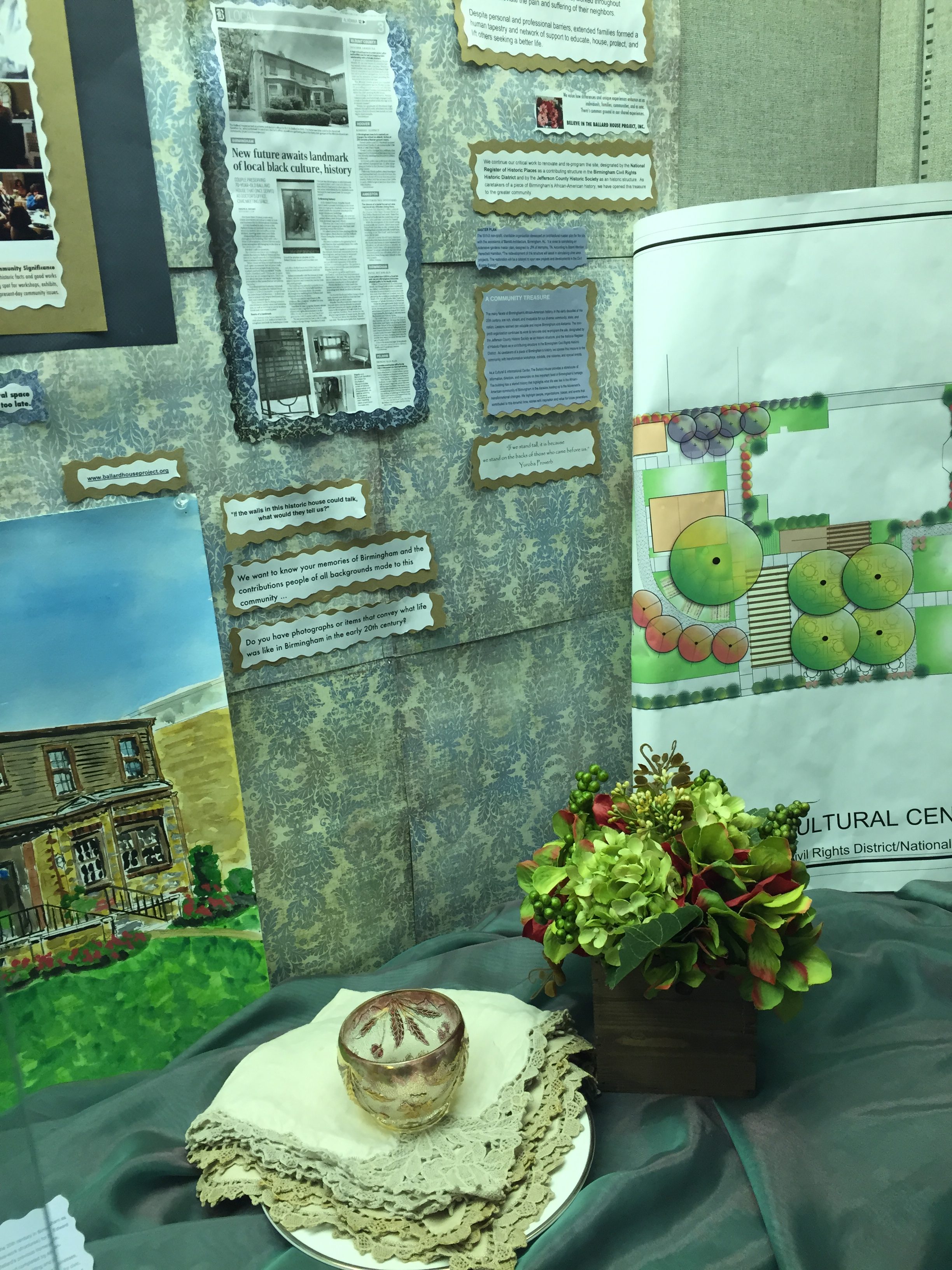

Currently, the Ballard House Project is conducting a $1 million capital campaign to raise funds to restore the building.

“We want to fully restore the building,” Hamilton said. “[We’ve been making improvements] little by little throughout the years as needed, but we know full restoration of this building is critical. We also have already started on the development of a master community garden, which … will be in the lot next door. This plan also includes infrastructure for permanent exhibits, … [both] interior and exterior.”

In addition to the special events and Talking Circles series, the organization hosts community conversations and collaborates with other groups.

“We’ve hosted community conversations, … most of which are in different parts of the city, as well as sometimes here at the Ballard House and at several [local] libraries,” Hamilton said. “We’ve also hosted temporary exhibits, whether here or somewhere else, including one at the Taste of 4th Avenue Jazz Festival, where we’ve hosted exhibits [that enable] people to come learn more about their history.”

The Ballard House also does presentations at schools for students and adults.

“We want this to be a community initiative. That’s our focus,” Hamilton said. “We’re doing more than just unveiling what happened. This is a collaborative process with members of the community.”