By LaMont Jones

Diverse Education

Black youth, especially males, have been disproportionately tied to the U.S. justice system far longer than today’s headlines suggest.

Dr. Carl Suddler, an assistant professor of history at Emory University, puts the intersection of race, gender, youth and incarceration under a searing spotlight in his new book, Presumed Criminal: Black Youth and the Justice System in Postwar New York.

When the justice system began to become more about punishment than rehabilitation in the 1950s, he writes, criminalized Black youth bore the brunt of the shift as law enforcement began to devote more resources to issues of juvenile delinquency. In New York City, in particular, heightened surveillance of Black neighborhoods and controversial practices such as stop-and-frisk drove up arrest, conviction and incarceration rates of Black males for decades.

Add in historically sensational media coverage of crime – from the Harlem Six to the Central Park Five to Trayvon Martin – and the so-called War on Crime and War on Drugs from the late 1960s into a new millennium became, in the eyes of many, a war on Black men.

Legislative policies and police practices at national and local levels helped create what exists today – a carceral state impacting Black and Brown people, especially males, with long-term implications for families, communities and the nation.

“Bridging the historiographical gap between the Great Depression and the War on Crime,” Suddler writes in Presumed Criminal, “I argue that black youths faced a more punitive justice system by the post-war era that restricted their social mobility and categorically branded them as criminal – a stigma they continue to endure.”

Suddler recently talked with Diverse about the book.

How is the topic of juvenile justice personal to you?

Juvenile justice ought to be personal to everyone. How we treat our young people, especially those who have been labeled – often unjustly – delinquent has reproving consequences on the future of our criminal justice system and our nation as a whole. I like to believe that if we are going to see change in the legal system, it can start with our youths.

The book makes the case that high and disproportionate Black youth incarceration is not a recent phenomenon. Why does much of the public believe the myth?

I think we are always guilty of the moment and consider our contemporary problems as something new. And we’re not necessarily wrong. However, it’s important to remember that everything has a history. In Presumed Criminal, I point to a pivotal moment in juvenile justice history when state responses to delinquency increasingly criminalized Black youths and tethered their lives to a legal system that became less rehabilitative and more punitive.

You chose New York City as the subject of your research and analysis for some specific reasons. What are they?

On the one hand, New York City lends itself well to comparisons with other large U.S. cities, especially Northern cities, where its citizens confronted, resisted and challenged the racial status quo. This included contests over fair housing, public schools and the criminal justice system – all spaces that affect the everyday lives of the city’s youths. So, in some ways, New York City is representative of the nation as a whole. On the other hand, it is important to reveal how one of the most liberal cities in America also led the way and employed some of the most extreme police practices and policies, such as stop-and-frisk, that impeded Black life. Its local history is filled with stories of progress and backlash.

What’s your general view on current and proposed government policies and their actual or potential impact on Black youth criminalization and incarceration?

I like to think that I am a hopeful realist. It’s in the balance that I am able to fend off the feelings that the work that I am doing is not futile. I also think it is important to point out that the work that I am doing is only a small part in relation to the work of activists and organizers committed to being on the ground every day. In this protest and action, we are able to put pressure on state authorities to make efforts toward changing their policies and positions. And history matters here. Far too often when state governments, and also federal governments to a certain extent, put forward new legislation they think will correct systemic issues in the legal system, we tend to rinse and repeat methods from the past.

I think this is particularly true in our efforts to prevent crime. Regularly, legislators and lawmakers alike think addressing potential crime will nip the problem in the bud, when in reality, extensions of police authority prove to do little more than increase arrest rates. This was true in the first decades of the twentieth century, and it continues to hold true today. For example, when the New York Police Department made the decision to document “potential delinquents” in the 1920s and 1930s, these youths comprised a majority of the caseloads in court. Today, especially with the increased technology, we see police departments – including the NYPD – utilizing various databases and surveillance tactics to document “potential delinquents” in the name of crime prevention and, again, the increased police contact, unfortunately, means higher arrest rates. This proves to be incredibly precarious for Black youths, who in 2017 outnumbered White juveniles in New York City more than 15 to 1.

What similarities or differences do you see between Black and Hispanic/Latino youth in terms of being “overpoliced and underprotected?”

More similarities than differences, unfortunately. It’s important to point out, however, that geography can influence this experience. But in New York City, for example, Black and Latino stop-and-frisk numbers are often paired because Black and Latino men continue to be the overwhelming targets of activity. According to the New York Civil Liberties Union, young Black and Latino males between 14 and 24 account for 5 percent of the city’s population and make up 38 percent of reported stops – they were innocent 80 percent of the time. Even as the number of total reported stops continues to decline, the racial disparities continue to prevail.

Any big surprises during the decade you spent researching and writing the book?

In the afterword, I share a little insight about my experience writing the book. I started writing in the wake of Trayvon Martin’s untimely death in 2012. I was a graduate student at Indiana University in Bloomington, and in that moment, I was having a difficult time dissociating the past from the present. When I was in the archive, when I was reading historical accounts of youth encounters with the carceral state, I couldn’t help but consider the present moment. So, as a historian, who was tasked to find change over time, it was the sameness that continued to resonate. I remember following the Ferguson uprising, closely, and seeing the similarities in the Harlem uprising of 1943. I remember watching the mothers of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner and Tamir Rice speak together for the first time in 2014 and seeing the connection to the mothers of the Harlem Six from 1964. So, unfortunately, I think the surprises came in the form of what appeared to be such little progress and the slightest changes over time.

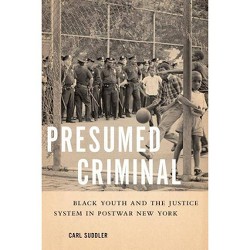

What’s the story behind that compelling cover photo?

I love the cover image for several reasons. It’s a photo from 1966 Brooklyn. The patrolmen in the backdrop are amongst the 1,500 that were assigned to the neighborhood and, what I often like to point out, is the “diversity” amongst the ranks. There is no information related to the ages of the boys in the image, but you can gather that they are all relatively young, especially the youngster peering out into the camera from the hole in the fence. At its core, however, I feel this image captures the crux of the book – and the heart of the problem today – and that is how normal the over-policing of Black and Brown communities has become. The boys continue to play ball; the officers continue to stand pat. Their proximity does not appear to phase the youngsters. However, we all know too well that increased interactions with the police often lead to increased arrest rates, arrest rates dictate “crime” statistics, and as a country – because we have yet to figure out a better alternative – we rely on crime statistics to make sense of who is “presumed criminal.” Whether or not they committed a crime becomes moot.

LaMont Jones can be reached at ljones@diverseeducation.com.