By Solomon Crenshaw Jr.

For the Birmingham Times

The top shelf of the pro shop at the Highland Park Golf Course in Birmingham’s South Avondale area easily doubles as a hall of fame, a place where monogrammed golf bags of several notable players can be found.

There’s the University of Alabama’s Justin Thomas and the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Graeme McDowell. So, too, are Vestavia Hills, Ala., native Smylie Kaufman, as well as Ricky Fowler and Jordan Spieth, all players on the Professional Golfers’ Association (PGA) Tour.

Some might think one bag—Lee Gurley’s—doesn’t belong because he didn’t play on the PGA Tour and didn’t garner the acclaim of the others on the national scene. Those who know the game know better.

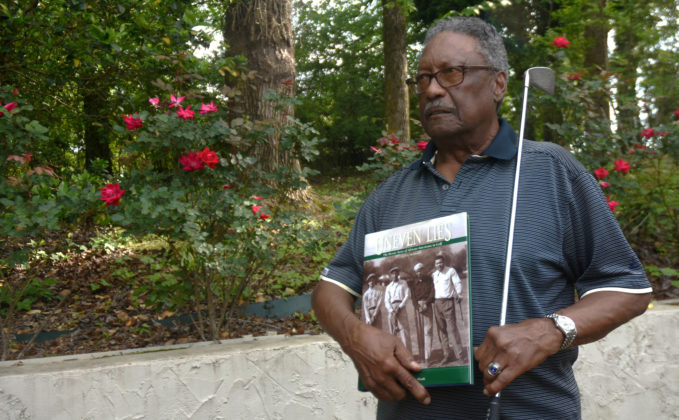

Gurley’s place among Birmingham’s golf greats is well established. He was one of the first African Americans to blaze a trail on the cart paths, beginning as a caddy and then as a player and instructor. Even now, Gurley, 82, can be found most days at Highland Park, where he’s worked for the past 45 years.

Many recognize him as the starter, the staffer who gets patrons’ rounds under way. Some may remember him from his previous stints as a caddy, a cook, and an icon who taught the game at the golf course. What many don’t know is that Gurley shot a score of 58 about 10 years ago to set the course record at Highland Park—a mark that stood until Cincinnati, Ohio’s, Kevin Hall, a deaf African American golfer, bettered that by one stroke about five years ago.

But the soft-spoken Gurley is part of a deeper story, one that goes to the very roots of blacks in the game of kings.

These days, golf is on the minds of many in Birmingham and beyond. Just last week, the Regions Tradition brought the best senior players in the world to the Greystone Golf and Country Club in Hoover. This week, everyone is seeing green as Tiger Woods, fresh off his return to major golf success with his fifth Masters Tournament championship, is pursuing major title number 16 at the PGA Championship on the Black Course at Bethpage State Park in Farmingdale, N.Y. With Woods dominating the national scene and raising the profile for golfers of color, it’s an ideal time to recall several of Birmingham’s black golfers who have earned their place in history on the links.

“Tried to Help Momma”

Gurley stepped into the game at age 8.

“I figured I’d start caddying, trying to help my [mother and] make a little money,” he said. “My dad had died, and I tried to help momma with my brothers and sisters.”

Despite being right-handed, Gurley started playing left-handed because those were the only clubs he could get.

“You couldn’t find right-handed clubs because most of the golfers were right-handed, but you could find left-handed clubs anywhere [because] maybe one or two golfers were left-handed,” he said.

That changed when Gurley moved to Connecticut and worked at Hartford’s Keney Park Golf Course. The head pro there taught Gurley to play right-handed, and his game took off.

“I got to be a good golfer,” he said. “I couldn’t hardly get no game then. Nobody wanted to play me. I was too good.”

Gurley played in tournaments throughout New England for 25 years and eventually became head pro for 10 years at Keney Park. In 1975, Gurley returned to Birmingham and ran the Beacon Hill Golf Course in North Birmingham until it closed. It was one of two courses where blacks were allowed to play, initially on a limited basis.

“Beats the Mall”

Frank Albert Bates, 85, has lived most of his life at Birmingham’s Roebuck Golf Course.

“It’s where I was raised,” he said. “I just hang out there. It beats going to the mall for me. It’s something to do, somewhere to go.”

At about age 13 or 14, around 1947, he became a caddy at Roebuck, earning 65 cents for 18 holes, perhaps as much as $1.25 to $2: “It was just a way to make money,” Bates recalled.

Nowadays, caddies are rare at the facility. At top-name courses, the day rate may be about $60; a caddy who is thought to have done a good job could earn tips of up to $100.

Eventually, when Bates was about 16 or 17, he wasn’t content to simply clean the clubs and provide yardage estimates to white golfers. He wanted to participate.

“We’d have to slip out there and play,” he recalled. “They’d chase us off the golf course if they knew we were out there. They’d give you a club, or you could buy them at the pawn shop. Sometimes we’d play with one club, three or four of us.”

Black caddies were given a day—usually Mondays, when the course was closed—to play at private courses, like the Birmingham Country Club or Vestavia Country Club, but not at public courses like Roebuck.

“Beat it Around”

Not every African American in metro Birmingham started out as a caddy. George A. Washington of Forestdale began as a 10th grader at A.H. Parker High School.

“We didn’t have golf team at Parker High School, we had a golf club,” he said. “You know, like the French club or the Spanish club. We had a golf club.”

The boys’ advisor took Washington and about half a dozen other students to the Cooper Green Golf Course in Powderly Hills once or twice a semester and they “beat it around a little bit.”

“[The advisor] had some old clubs he’d let us use,” Washington said. “We’d hit balls on the practice greens and maybe play a few holes. We got an idea of what a golf course looked like.”

That was about 1959. Back then, few people had televisions and there was little golf on TV.

“When we were growing up, we played baseball, basketball, stickball, all types of balls,” Washington said. “We also played golf. My uncle, who lived across the street from [my childhood home], had a set of golf clubs. We beat them to death—on the lawn, sidewalk, anywhere. We played with them in the backyard. We put cans on the ground [and] putted into them.

“At that time, basically, you didn’t have a lot of people who even played golf or knew what golf was.”

The Vulcan Club

These days, Washington is a member of the Vulcan Club, which plays a few times each week. Club members include Jesse Lewis, Birmingham Times founder and publisher emeritus; Charles Townsend, retired Jackson-Olin (J-O) High principal; and Otis Windham Jr., who has served as an advisory board member for African American Golfer’s Digest magazine since 2009. Windham was also tournament organizer and coordinator for the annual Pete Ball Memorial Neck Bone Golf Tour in Miami, Fla., from 1998 through 2009.

Townsend, a teacher at J-O when he started playing golf, often accompanied physical education teachers to the Cooper Green course to play nine holes after school.

Lewis recalled working in sports marketing for Coca-Cola, arranging golf events for blacks all over the country.

“I had knowledge of [the sport], but I had to go get some clubs and start playing,” he said, admitting that his greatest motivation was to help his business dealings. “If you can’t sell somebody something in four or five hours, you can give it up.”

To read more stories of golf in Birmingham, click one of the links below.

Chris Osborne Lost Leg in Motorcycle Accident; Became Champion Golfer

Miles Coach Leonard Smoot to be inducted into Golfer Hall of Fame