By Ameera Steward

The Birmingham Times

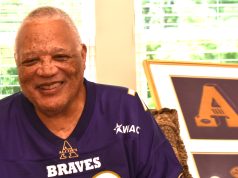

She’s known simply as “Mrs. Mosley.”

Elected officials, corporate titans, civic leaders, neighborhood officers all know the blunt Maralyn Mosley, who, at age 81, will tell you that she continues to fight for what she believes in—and no one will disagree.

Mosley went toe-to-toe with the Jefferson County Commission when a majority downsized Cooper Green Mercy Hospital in 2012. She helped found a community-health center when she lived in New York. She was a volunteer for the Rev. Jesse Jackson’s 1980s presidential campaign. She was a huge supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment in the early 1970s.

She also spoke before the Alabama State Senate and U.S. Senate in the early 1990s about abortion before it became a wedge issue among politicians and voters. Mosley said she has had two abortions: the first after she was raped at age 13, and the second, which she performed on herself “with a set of knitting needles,” when she was in her 20s.

“Everybody says that pro-choice means you are pro-abortion,” Mosley said. “I support the woman in what she decides to do. If she decides to terminate the pregnancy through abortion, I support that. If she decides to carry the pregnancy to term, I support that.”

Mosley said she will do everything she “thinks [is] necessary for [a woman] and her baby to have housing. She should have enough money to live on, whether she is married or single. She should be able to take care of herself and her family.”

The recent decision by Alabama’s GOP-dominated Senate to make performing an abortion at any stage of pregnancy a felony punishable by up to 99 years or life in prison for the abortion provider—and signature of the bill by Gov. Kay Ivey—was “absolutely an abomination,” Mosley said.

“I listen to people on the radio, and they say terrible, terrible things about women. … That’s the reason I say people in Alabama are pro-birth; they’re not pro-life. … If you were pro-life you wouldn’t … make those kinds of terrible, uneducated remarks about women.”

Anyone who is pro-life should make every effort to “make the life of that child who is here and the mother of that child [such that] they will be able to sustain themselves and be able to have the kind of life that will [enable them] to be successful,” she said.

Activism Begins

Mosley, born and raised in Birmingham’s Elyton community, has been fighting for one cause or another ever since she can remember.

At age 19, she moved from her hometown to New York around 1957 to become a housekeeper because the company in New York paid more than she was getting for doing the same work in Birmingham. At the time she had one son who was being raised by her mother in Birmingham. When she moved North, he stayed behind.

New York is also where Mosley’s activism began. She and a friend worked for Westchester County at a women’s center when they went to the administrative offices of the bus system in Yonkers and asked the general manager if he had ever thought about hiring women.

“This is the 1970s and he said, ‘Well, we don’t think women’s wrists are strong enough to be able to hold the steering wheel of the big buses.”

It sounds ludicrous now, Mosley said: “[In the 1970s] in Westchester County, there were no women bus drivers working for a county-funded bus system, where the women, … too, were paying taxes.”

In addition to helping women pursue work in nontraditional fields at that time, Mosley and her friend also fought to support the educational aspirations of women by getting the New York Department of Social Services (DSS) to fund day care slots for those who chose to go back to school.

“[The agency] did it for women going to work but not those going to school. Some county officials didn’t understand the importance of education,” Mosley said.

Eventually, DSS agreed to pay for half the day, but not before Mosley and her friend organized a demonstration at the county office building. Moms brought their children, “pampers, and lots of milk,” Mosley said.

“We had the babies and mothers in the hallway. The mothers were changing pampers. … The toddlers were running up and down the hallway. … We had great fun,” she laughed.

It was important to provide opportunities for women because “if you educate a woman, you educate the family,” Mosley said. “That woman is going to make sure her children are educated.”

Women’s Rights

Also while in New York, Mosley and a group of women helped found a community-health center that was funded by one of the larger corporations in the area. At the time, Mosley and family were living in Greenburgh, N.Y., and the only local doctor moved out of the community.

“Most of the women at that time did not drive. I was one of them,” she said. “A nurse at the … preschool said to a group of us women, ‘You know, you can start a clinic.’ We had never thought of that.”

The nurse told them they could hire their own doctor—so Mosley and the women in the community did just that. They also brought on a director, a pharmacist, and a pediatrician. Westchester County gave them three public-health nurses; the American Red Cross gave them a station wagon to transport patients to and from their homes; and three community-outreach workers from the neighborhood signed up Greenburgh residents to open a health clinic in Westchester.

“It was an adventure to say the least, … but we made a go of it,” Mosley said.

Back to Birmingham

Mosley returned to the Magic City in the midst of a divorce in the 1980s. She volunteered for Jesse Jackson’s presidential run, met a group of activists, and “became active in the things they were active in.”

She devoted much of her energy to health care, public housing, and youth programs, and served on the board of Partners In Neighborhood Growth (PING), which she said was “one of finest youth programs in the state of Alabama.”

Mosley fought with vigor to keep Cooper Green Mercy Hospital from closing because doctors there “saved my life.”

“I love Cooper Green. … I want everybody to have the same chance I had, she said, recalling a time when she had high blood pressure, but didn’t know how high. She drove herself to Cooper Green’s emergency room, where she got the medical attention and care she needed.

Mosley supports a University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB)-led health-care authority for the facility, she said, “[because] I think … that’s going to save Cooper Green.”

She also fought for the Cooper Green Homes, where she has lived since 2009. Looking at Cooper Green now and how happy her old neighbors are, she said, “It was worth the fight”.

Mosley has “no regrets” about her activism: “I always said, ‘If I make things better for me, they will be better for you.’ I always wanted to make things better for my family and myself. If I was going to make things better for my family and myself, I [wanted other families to] benefit, too.”