By Ameera Steward

The Birmingham Times

Civil Rights Movement tactics may change, but the objectives shouldn’t, said Doris Gary, 85, who participated in the marches of the 1960s and lived in Collegeville when the Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth was pastor of historic Bethel Baptist Church.

“We’ve got so many people now that have so many different opinions about how things should be. We need to come together and be on one accord,” said Gary, who was a member of Shuttlesworth’s Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights.

“Now, you’ve got demonstrations all over the world, but they’ve got different issues. Ours was a collective effort to end segregation, and that’s what we accomplished at that time. New laws were passed.”

Iva Williams, 49, vice president of the Outcast Voter’s League, said he sees a younger generation that’s “fed up” but in a different way than in the past.

“Millennials have a different outlook,” he said. “It’s a different level of fed up, I think. They just refuse to be held back, if you will. … That’s why it’s incumbent upon guys like myself and … other people … to provide them some boundaries. We have to give them some things to think about. We have to hold them back because … these young people protest a lot differently.”

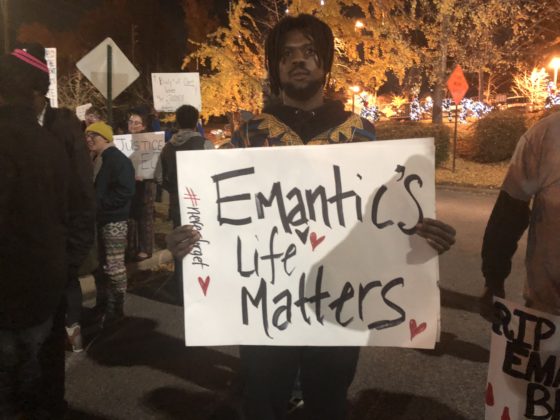

Some recent demonstrations have involved protests like the one Tuesday evening outside Hoover City Hall after Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall said a Hoover police officer took justifiable action in the shooting and killing of 21-year-old Emantic “E.J.” Bradford Jr. at the Riverchase Galleria mall on Thanksgiving night.

Protesters have also made visits to the home of Hoover Mayor Frank Brocato and the Montgomery neighborhood of Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall; and the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute (BCRI) after its board rescinded a decision to present the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth Human Rights Award, to renowned activist and Birmingham native Angela Davis, PhD—a decision the BCRI has since reversed.

The Rev. Arthur Price, 53, pastor of downtown Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, said the objective of protests remains to shine a light on injustices and inequity, so “the community at large might be able to see what this small segment of the population sees [and] to make sure they understand the blight that’s going on in the community.

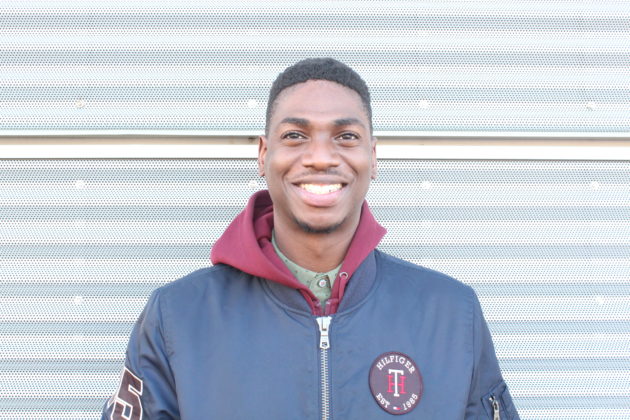

Martez Files, a 27-year-old organizer for the Black Lives Matter movement and an African-American studies professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), said some often forget the goals of the marches, “why we were doing this in the first place,” he said, before Marshall announced his decision on the Bradford, Jr. shooting. “I know you get so caught up in, … ‘I gotta fight.’ ‘I gotta resist.’ ‘I gotta protest.’ ‘I gotta show up.’ … Then we lose [sight of] why we were doing it.”

“Hateful Acts”

In Birmingham 55 years ago, there was no doubt why the protesters marched.

“The enemy in 1963 was very obvious: [Birmingham Commissioner of Public Safety Theophilus “Bull” Connor] and the white establishment. They were the enemy, and they were very vocal and very pronounced in their determination to keep blacks in their place,” said the Rev. Dr. Christopher Hamlin, pastor of Tabernacle Baptist Church in West Birmingham. “Now, the enemies … are not as well-known and obvious as they were in 1963. Those attitudes that were very obvious in 1963 may not be as obvious today, with the exception of the number of African-Americans that have been shot, killed, or gunned down by law enforcement officers.”

In addition to Bradford being shot and killed last year by a Hoover police officer, several other young black men have been killed under suspicious circumstances that generated national attention and outrage, including 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, who was shot and killed in 2012 by a neighborhood watchman in Sanford, Fla.; 18-year-old Michael Brown, who was shot and killed in 2014 by a police officer in Ferguson, Miss.; 12-year-old Tamir Rice, who was killed in 2014 by a law enforcement officer in Cleveland, Ohio; and 32-year-old Philando Castile, who was shot in front of his girlfriend and her daughter in 2016 after being pulled over in Falcon Heights, Minn.

“In terms of beatings or violence, … especially upon African-Americans, they did it then, and we see in some of these cases now that this stuff continues to happen today,” Hamlin said. “In many of these situations, it’s all … racism. Racism breeds, produces, stimulates hateful acts. So, if someone exhibits racism or is a racist, that can come out in multiple ways.

“If you’re a police officer, it could very well be mistreatment of blacks or Hispanics. If you’re a loan officer, it could be to give someone a harder time to try to secure a loan for a home or a car. If you’re a realtor, you might put up a lot of roadblocks if someone wants to move into a certain neighborhood. That stuff continues to happen, unfortunately.”

Lessons Learned

Williams said the younger generation should be careful not to abandon all the principles of the past.

“Sometimes young people almost run away from anything that has been done in the past,” he said. “If our elders did a sit in at a lunch counter, [today’s young people] want to go in and take over the whole lunchroom. … It just seems like they want to take things a step further. Sometimes that’s good, and sometimes that’s very dangerous because their wanting to take things a step further can sometimes challenge the law, and that’s something we are so intent on not doing. … We just want to exercise civil disobedience.”

Gary said there are lessons to be learned from what happened 55 years ago.

The Civil Rights Movement “accomplished what we wanted to accomplish,” she said.

“We were demonstrating against the injustice of segregation, and laws were passed during the times that we demonstrated. … They removed the [separate] water fountains. They removed the … ‘Colored’ and ‘White’ boards from the school buses. They integrated the school systems. [We] were able to get jobs. [We] were able to vote.”

New generation of Birmingham protestors step up

By Ameera Steward

The Birmingham Times

When protests were held in Hoover, Ala., on Tuesday evening after Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall said a police officer took justifiable action in the shooting and killing of a 21-year-old black male, noticeably absent were members of the clergy who were at the forefront of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.-led Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s.

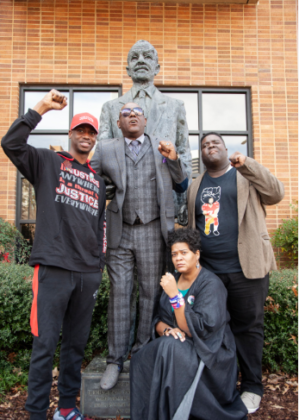

“This is not your grandfather and your great-grandfather’s protest. This is the 21st century,” said activist Frank Matthews, founder of the Outcast Voters League and chief advisor to the Birmingham Justice League. “Granddaddy’s protest didn’t go to elected officials’ homes. They didn’t go to district attorneys’ homes. They didn’t target individual businesses. … [Today], nothing is non-protestable.”

Matthews and members of his groups—including Carlos Chaverst, president of Birmingham Justice League and secretary of the Outcast Voter’s League, and Iva Williams, vice president of the Outcast Voter’s League—have taken to the streets and City Council chambers and beyond to call attention to recent protestable events.

They were out again Tuesday night in Hoover with National Civil Rights Attorney Ben Crump and the family of Emantic “E.J.” Bradford Jr., who was shot and killed at the Riverchase Galleria mall in Hoover on Thanksgiving night.

The local groups have held protests not only at various locations around Hoover but also at the home of Hoover Mayor Frank Brocato and in the Montgomery neighborhood of Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall and more are planned, they say, now that charges will not be filed against the Hoover police officer.

In addition, protesters met with members of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute (BCRI) board after it rescinded a decision to present its highest honor, the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth Human Rights Award, to renowned activist and Birmingham native Angela Davis, PhD. In the wake of criticism; the BCRI has since reversed that decision.

Matthews said he believes King would support any group fighting against injustice, including the “Foot Soldiers” of today.

“King once said, ‘We want all of our rights. We want them here, and we want them now,’” Matthews said. “That’s … what the 21st century Foot Soldiers are doing.”

“Anger into Advocacy”

The Rev. Arthur Price, 53, pastor of downtown Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, said King learned how to turn anger into advocacy.

“King was a person who may have been angry about the state of America, angry about segregation, angry about people being disenfranchised, angry about not having proper rights, but he turned his anger into advocacy,” said Price. “He didn’t just spew out anger. … He began to advocate for change in America.”

The Rev. Dr. Christopher Hamlin, 59, pastor of Tabernacle Baptist Church in West Birmingham, said, “If you’re just marching for the sake of marching, not knowing where you’re going or where you’re leading people, I’m not sure how beneficial that is. Anyone who protests needs to know what the end game is, what [they] are protesting about, what demands [are being made], and [what] plan [is in place] to make all of this happen.”

Bishop Jim Lowe, senior pastor of Guiding Light Church in East Birmingham, said he can see the difference between King’s movement and some—not all—of the ones that are active today.

“I’m not speaking about any specific movement here, [but] most of the things we see in our society today demean other human beings,” said Lowe, before the Alabama AG announced his decision on the Bradford Jr. shooting. “King never did that. He always respected the human worth and dignity of everyone. There’s a great deal of name calling and a lot of use of the N-word … with some of the things that happen now. They demean people [and] mischaracterize other human beings, which would never have been accepted under King or [the Rev. Fred L.] Shuttlesworth, the people of the movement of my day.”

A Great Example

Leaders during the 20th century Civil Rights Movement set a standard for today’s protestors, said area clergy.

One example, according to Pastor James Tyus, 59, of Galilee Missionary Baptist Church in North Birmingham, is “stick to what you believe and stick to what you know is right but do it in a way that is honorable before God, … be peaceful about it. … when you do it in a peaceful manner, God honors that.”

Martez Files, a 27-year-old organizer for the Black Lives Matter movement and an African-American studies professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), said King, as an example for activists and organizers, “represents the ways we can navigate space, navigate power structures, bring folks together across generations, across religions. … King was a unifier and, I think for someone like me, King also fought against an imperialist government. He didn’t believe big powerful countries should go in dominating smaller countries. He knew there was a way for people to be sovereign, have their liberty, and have their dignity intact. So, I think … King sets multiple examples for activists and organizers.

“I definitely do believe the example that [the Civil Rights Movement] set for us was to make sure love is present, at the center of what we do, to make sure we are accountable to our community. I know we learned that from them.”

Lowe said the Civil Rights Movement was focused on changing the hearts of those who were against the fundamental principles of the Word of God.

“You called him Dr. Martin Luther King, but remember this, he was reverend before he was doctor. He was a man of biblical status,” Lowe said. “He was person who honored God before he honored the culture. His honor, his authority, his truth came from the Word of God, not from the principles of man. … The fundamentals of truth that [King] got were from the Word of God, the Bible, and not from the principles of men, our government.”

Many forget that King was a sophisticated thinker and an incredible organizer, Files said: “They had training. They had workshops. They had classes. They had ways for people to engage across generations. They met at churches. They fed people, fed the community as those folks trained. I think we have tried to model some of that, but I actually believe we have not implemented that as soundly as they did.”

Clergy

The Rev. King and the Rev. Shuttlesworth, as well as the Rev. Ralph Abernathy and the Rev. Charles Billups, were at the forefront of those marches 55 years ago. Now, demonstrations seem to be led mostly by activists on the local and national levels.

“Sometimes, when we have major issues like the issue at the Galleria, some of the clergy you see, you don’t see them until television cameras, news media,” are around, said Tyus, who wonders if some clergy have the issues at heart.

“When I say they don’t ‘have it at heart,’ … [I mean] if you have the people at heart, it shouldn’t take a shooting or any other type of catastrophe to bring you out,” he said. “Maybe they feel the [urgency of the] protest, but don’t wait till you have to do something behind a killing … [to be] with the people.”

Instead of waiting until a high-profile event happens, Tyus said, tutor and mentor some young men. Sit and talk with them.

“A lot of our young people don’t understand really what’s going on right now. They think it’s normal because so much of it happens that they think it’s just a part of life,” he said. “When I was coming up and the protests were going on, the hoses and all of that stuff, our elders—the clergy and the preachers—would sit us down and talk to us about what was really going on.”

Outcast Voter’s League vice president Williams said he’s walked and worked with several “young people of faith, but they don’t go to church.”

“Many believe in God, but they don’t have anyone they can call pastor,” he said. “Part of that is because they have lost faith in the faith-based community. They have seen people do wrong and other pastors don’t stand up and say anything about it.”

Hamlin said clergy are active today in many ways, pointing out Faith in Action Alabama’s Birmingham Peacemakers, a movement that calls the faith community together to respond to violence. The organization is made up of “clergy persons who take to the streets … and work to honor God by achieving systemic change to create pathways of opportunity for all Alabamians,” he said, adding that the group has several peace walks in various communities, including Birmingham’s West End.

Price said the clergy is at work even when you don’t see them patrolling neighborhoods.

“There are some things clergy do behind the scenes to bring peaceful resolutions to situations,” he said. “We meet with certain groups. We talk to our congregations individually as pastors… Clergy also meet together as a group to talk about ways that will bring about peaceful resolution. … We talk about current issues that affect the community.”

Price added that no one can play the role King did.

“I think a lot of people get into maybe not seeing clergy [because] King is such a megafigure, [and] no one sees a figure like King,” he said. “I think a lot of clergy have taken pieces of King and taken up the mantle of his mantra in [different ways].”

Click here to read what local clergy have to say to current activists about their protests.