By Andre Perry and Michael A. Lindsey

The Hechinger Report

Nine-year old McKenzie Adams was “a real sweet girl,” a “straight-A student” who wanted to be a scientist, family members told ABC News. She held so much promise, but now McKenzie may be added to the small and alarmingly growing number of black children between the ages of 5 and 11 who are committing suicide. On December 3, she was found in the home where she lived with her grandmother in Linden, Alabama. The Linden Police Department have yet to rule the cause of death a suicide but are investigating the death as such.

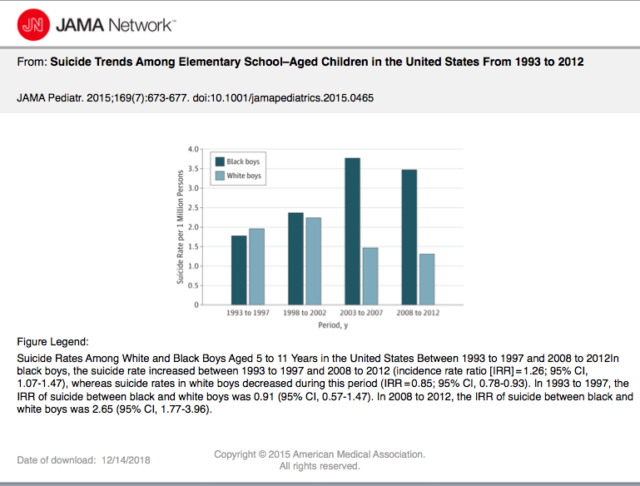

Between 1993 and 2012 suicide rates doubled among black youngsters ages 5-11, while rates declined among white children in same age group, according to a 2015 article published in the academic journal JAMA Pediatrics. The suicide rate cited in that study is roughly twice as high as for black children as it is for their white peers. In absolute numbers, that’s 657 young black children — 553 boys and 104 girls — who took their own lives.

The growing number of suicides among black children demands deeper inquiry into the state of black kids’ lives and why a small but growing number are compelled to choose death over their circumstances.

McKenzie’s relatives wonder if racist taunts she received at school over her friendship with a white boy were a factor. Her mother, Jasmine Adams, said the school system let her family down, alleging that teachers and administrators ignored the girl’s complaints. The school denies receiving any reports of bullying.

Notwithstanding the particular details of the case, we know interactions between students, teachers and families at school can spark, aggravate — or improve — the mental wellbeing of students. Black children are more likely to be bullied in schools. All school leaders must see themselves as a significant source of prevention and detection.

On Nov. 20, 2017, Rylan Thai Hagan of Washington, D.C., was at home. The 11-year-old’s mother, Nataya Chambers, had gone out to run some errands and said that she would return in a few hours. She called Rylan on his cellphone while she was out and said, “When I return I want you to help me bring groceries into the house.” He said, “Okay.”

Chambers came home and knocked at the door. She called out, “Rylan, come help me with these bags. I told you I needed some help.” Rylan didn’t respond.

So she set the groceries down and went to his room, and discovered he had killed himself.

Michael A. Lindsey, executive director of the NYU McSilver Institute for Poverty Policy and Research (and a co-author of this column) recently interviewed Chambers to understand the circumstances surrounding Rylan’s suicide. His mother didn’t know of any mental health issues. He was an honor roll student and participated in sports.

But symptoms of depression manifest differently among adults and adolescents. School personnel should be aware of the symptoms that parents might not be equipped to recognize.

For example, instead of showing despair or withdrawing, a child may display somatic symptoms, complaining for instance about how their head or stomach hurts. Teachers may also see persistent boredom or increased irritability, anger or hostility that children may not present or parents may not see at home. The long periods of time that students spend in school give educators an opportunity to see irregularities. They should be able to spot potential underlying issues behind a students’ trouble with schoolwork or a disciplinary problem that needs to be explored.

However, many schools don’t facilitate what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) calls “school connectedness,” which it defines as “the belief held by students that adults and peers in the school care about their learning as well as about them as individuals.” When student feel a part of a positive community, they are more likely to engage in healthy behaviors, including seeking help when problems and conflicts arise. Schools may or may not be a part of the problem, but they most certainly have to be a part of the solution.

So much more work needs to be done to discover what is at the heart of the rise in suicides among black children. Last week, in a congressional staff briefing hosted by Rep. Bonnie Watson Coleman (D, N.J.), Dr. Lindsey called for the creation of a national taskforce to look at and try to understand the reasons why black boys, in particular, are committing suicide at higher rates than boys in other groups, and why it is happening at an increasing rate. A national taskforce would help to raise awareness and direct resources toward research and solutions, including guidance that educators and school personnel could use to spot suicidality in black children, and address it before the worst happens.

Suicides are not a failure of youth’s ability to cope as much as they are a catastrophe of adults’ inability to respond.

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), or the Crisis Text Line — text TALK to 741741 — are free, 24-hour services that can provide support, information and resources.

This story about black children and suicide was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.