By Erica Wright

The Birmingham Times

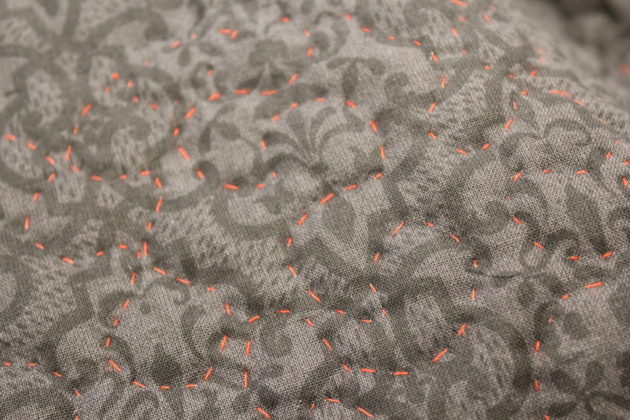

Quilts line the walls of the room where a group of women sitting at a long table talk, laugh, and bond together about the very thing that has brought them here: quilting. This is what happens in Birmingham’s Southwest community every Tuesday from 4 to 7 p.m., when the Riley Center Quilters meet to fashion their vibrant collection of quilts, some of which feature symbols of importance for blacks attempting to escape slavery via the Underground Railroad.

Quilting is a long-standing tradition in the African-American community, beginning with quilts made by slaves for themselves and for their owners. That history is not lost on members of the Riley Center group.

“We’re bringing back our heritage … with the Underground Railroad quilts. … It is who we are,” said Jeraldine Craig, who has been quilting since she was 7 years old and joined the center two months ago. “I just started [quilting again], but it brings back memories for me.”

The Riley Center has been around for more than 100 years, but the quilting program began in the early 1990s.

“I started the quilters because we had a craft class going on at the time. From the craft class, we started making quilts,” said Riley Center Executive Director Theresa McGhee Johnson, who is the founder of and an instructor for the quilting group. “[In the beginning], we had just a few people, but now it has grown.”

The Riley Center Quilters, now a group of about 25 members, have been recognized for their Underground Railroad quilts, which were on display during a traveling exhibit featured at the Birmingham Public Library, the Birmingham CrossPlex, and the Powderly Library. The quilts were part of a project the group worked on, “so everyone would be able to make their own quilt with the different symbols,” said Johnson. “I said, ‘When we finish, we’re going to do a show.’ And that’s what we did.”

Hidden Messages

The Riley Center Quilters started their Underground Railroad Quilts show in July, and they presented their designs at the Birmingham Public Library Central Branch in August; some were large, some were small, some were completed, some were not—but all revealed the hidden messages quilters once used to help slaves escape bondage.

During slavery, quilts were used as codes because they were the only means of communication, said Riley Center Quilters member Daphne Simmons.

“Nobody was going to get in front of a group of people and say, ‘OK, tonight you’re going to travel from this state to this state by going north,” she said. “There was a code, an unwritten code … passed down from person to person by word of mouth.”

Simmons explained what each patch or block meant on her quilt. For example, one patch had a wagon wheel.

“Wagons with hidden compartments were one of the primary means of transporting escaping runaways,” she said. “It was a message [telling escaping slaves] to pack provisions for their journey as if they were packing a wagon. Considering limited weight and space, they had to pack supplies essential for survival. … You couldn’t take everything, but you had to take enough so that you could survive.

Quilting Basics

For many members, it takes about two months to make a quilt, whether it’s sewn by hand or using a sewing machine. Materials are donated by churches and other groups, or members purchase their own materials.

Johnson said she likes to quilt by hand, “so it takes a while for me to finish projects. Now some of the ladies use a sewing machine to piece [together] their pieces. … It used to be that you had to sit, draw and cut [the pieces], and put them back together. Now you can do it faster on a sewing machine.”

Gwendolyn Wallace, 69, who has been with the quilting group since 2004, started out quilting by hand, but now she uses a sewing machine.

“I understood sewing because I had been doing that since I was 14 or 15,” she said. “I piece the blocks together by machine, and then I hand-quilt the rest.”

Carol Smith, 66, said quilting takes you back to school “because you have to know how to read a ruler and how to measure.”

“That’s the key to quilting,” she said. “You have to get your pieces correct. If you get [the measurements] off, the whole thing will be off from your designs to your patterns. If it’s something simple, I’ll do it by hand. But if it’s something like putting two or three pieces together and [having] to cut them again, it’s better to [use a] sewing machine … when you slice them, [so] it won’t come loose.”

True Sisterhood

Many of the Riley Center Quilters began quilting after they retired, and now it has become more than a hobby.

“It’s like a therapy session. It’s very calming,” said Wallace. “We get to interact with each other and meet new people, and we’ve learned an art that is dying. Being with the group, we’re fellowshipping and learning together. … It relaxes you, and you’re enjoying it while you’re doing it.”

Smith has been a member of the group for about four years, and she continues to attend despite recently having surgery on her knee.

“We’re a sisterhood, a true sisterhood,” she said. “A lot of us didn’t know each other until we started coming to the quilting class, and we help each other. We all like criticism. I can come in and say [to one of my fellow quilters], ‘Those fabrics don’t go together or that doesn’t look right. Let’s fix it.’ And [they] can come to me and say, ‘Those are not the right colors.’ We bring fabrics and say, ‘Look at this’ before we start cutting and piecing. … It’s relaxing, rewarding. It’s just a joy.”

Muriel Weatherly, 67, who’s been with the group for about two years, considers herself a beginner.

“I’ve made a lot of friends, and everyone is so helpful when I get stuck on something as far as cutting or trying to figure out what kind of combination of colors to put together,” she said. “We come here and don’t just sit off and quilt by [ourselves]. … We talk and laugh, and we help each other.”

Community Service

The Riley Center Quilters do more than just socialize. They’ve done service projects for soldiers, knitted caps for babies in neonatal wards, created lap robes for the Birmingham Veteran Affairs Medical Center Hospital, and made pillows for the Birmingham Police Department.

“We like to give back, too, because that’s what it’s all about,” said Johnson. “I’ve taught children in summer camp and after-school care how to quilt, and we’ve done many other service projects.”

The group visits area schools and conducts programs on the art of quilting.

“The reason I started teaching the kids is because we had after-school care [at the center], and when the kids would get done with their homework they would want to do something,” said Johnson. “I would always have blocks cut up and ready for them. Then I’d give them a needle and a thread and a shoebox, … so when they came in every day, they could work on it. … Before you knew it, they’d have several blocks, … we’d put them together, and they’d make their own quilts.

“What you learn is for you, but it’s also to share. I don’t mind sharing and teaching people because it’s history.”

Interpreting the Codes

The Riley Center Quilters present their Underground Quilts at various venues as a history lesson. Historically, many quilts offered directions on how to escape from slavery; quilts were used as codes because they were the only means of communication. Here are the meanings of a few quilt patches.

Bear’s Paw: An instruction to go through the woods

“You would follow the bears’ paws, their path. … You’re also going to have to be careful and watch out for bears,” said Riley Center Quilters member Daphne Simmons. Animal footprints would indicate the best path through the mountains, she said: “Following those bear paws, they’re also going to be led to food and water. Animals are going to show you the way.”

Basket: Indicates a safehouse where supplies can be replenished

“Safehouses were those places [where runaway slaves] could stay overnight,” Simmons said. “They were homes they could stay and were safe until they continued on to their journey.”

Crossroads: Indicates a city where protection or refuge can be found

“The main crossroad was in Cleveland, Ohio,” Simmons said. “Four or five overland trails connected with Cleveland, and numerous water routes crossed Lake Erie into Canada and freedom. It’s awesome to me to know that these people did not have maps in their hands. When I visit someone in another city, I depend on [a GPS]. We’ve come a long way.”

Log Cabin: Indicates a safehouse if it features a black block

This symbol meant that a place was a safehouse where escaping slaves could go for protection and shelter, Simmons said.

Shoofly: Indicates a place for clothing

“They would help [fleeing slaves] dress to blend in with clothes provided at the sign of the bowtie, [the next patch],” Simmons said. “[They] couldn’t wear the same clothes [they] had on while running away. [They] had to dress up to blend in with the city folks.”

Sailboat: Indicates a water crossing

This symbol was to guide “slaves who could walk through town undetected to ships waiting to take them across the Great Lakes to Canada and freedom,” Simmons said. “There would be sailors there to help them cross the river and enter Canada, where the North Star, [the next block], would shine with freedom.”

Canada was the only place that offered “absolute freedom” for runaway slaves, said Edna Turner, member and historical griot of Riley Community Quilters: “There were some Northern states that empathized with slaves and did not agree with [slavery]. But the Southern states had more land, they had more power, they had more voice in Congress, and they had it written into law that anyone aiding runaway slaves could be fined and [were] required to turn them back in.”

-This post was updated on October, 11, 2018 at 3:02 p.m. to correct that the Riley Center is in the Southwest community of Birmingham and not West End. This post was also updated to correct the center visited Powderly Library and not West End Library.