By George Joseph

The Appeal

Wesley Shelton was dozing off on a park bench in Montgomery County, Alabama, when a police officer approached him in late 2016. The officer asked if he could search the 56-year-old Black man, and found a $10 bag of marijuana. Shelton was brought to jail, charged with a felony, and given a $2,500 bond because he didn’t have a consistent home address. Shelton couldn’t scratch up even the $250 required to post bond. So he sat in jail indefinitely, while prosecutors waited for a drug lab report from the state’s overburdened forensic agency.

For months, Shelton begged for a bond reduction and then just to plead guilty. In one letter to a court clerk, he wrote, “I’m [sic] admit my guilt. I was in possession of marijuana. I’ve written 5 time [sic] asking for a bond reduction. I’ve received not one answer, from the court. … I’ve never in my life feel [sic] so totally helpless, with no end. Help me please.”

After 15 months in jail, authorities finally allowed him to plead guilty to the felony, despite the state’s failure to test the drugs he was accused of possessing.

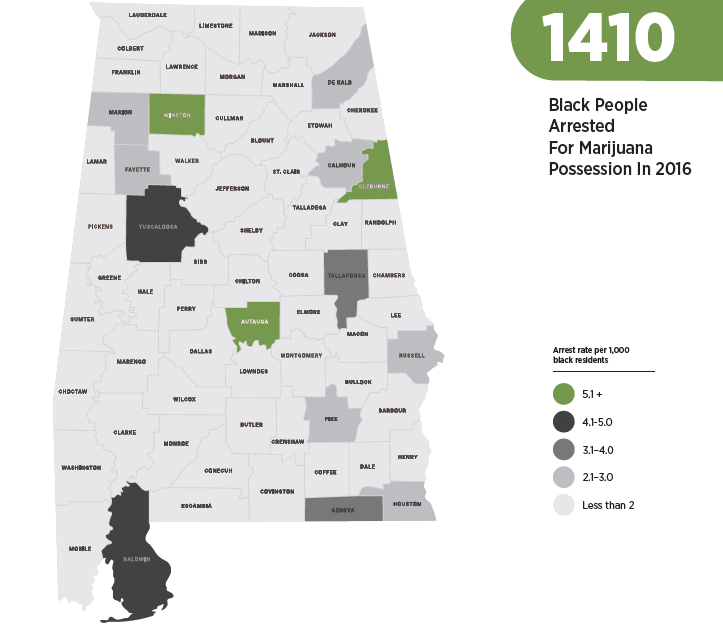

Shelton is just one of thousands of Black residents who have been harmed by Alabama’s “War on Marijuana,” according to a new report by the Alabama Appleseed Center for Law and Justice and the Southern Poverty Law Center.

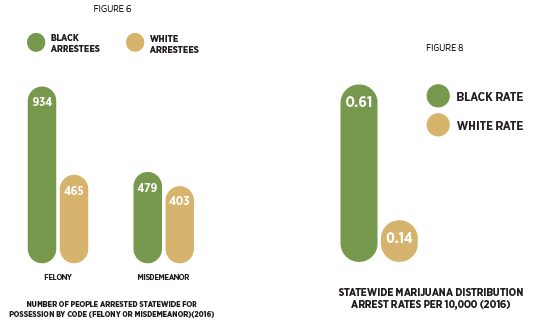

The report, released Thursday, found that Black people are four times more likely than white people to be arrested for marijuana possession in Alabama. Examining the 2,351 people arrested for marijuana possession in 2016, the latest year such data was available, the study found that 11 per 10,000 Black people were arrested on such charges, compared to only 2.7 per 10,000 white people. In possession felony cases, like Shelton’s, the researchers also found large disparities: Black people were five times more likely to be arrested than white people.

Out of the 20 most common arrest offenses in the state, researchers found that marijuana possession had the biggest disparity. But differences in arrest rates by race were particularly concentrated in a handful of counties across the state, the report found. Of the top 50 law enforcement agencies, ranked by marijuana possession arrest totals, the researchers found that seven police forces were 10 times more likely to arrest Black people.

The findings reflect the more intensive policing that Black residents face across the state, Alabama activists told The Appeal. “It’s a direct correlation with what we’re seeing on the ground,” said Carlos Chaverst, a Black Lives Matter activist in Birmingham. “Because we are still in the deep South and the Bible Belt, there’s still overt racism here.”

Beyond jail time, marijuana possession arrests result in numerous collateral consequences for residents, particularly those from Black communities. Those caught can face a six-month driver’s license suspension, lose student loan opportunities, and face stiff court fines and fees. A first-time possession conviction, for example, can lead to a $6,000 court fine.

The case of Mary Thomas, a 75-year-old Black grandmother and occasional marijuana user, highlighted in the report, illustrates how far a marijuana arrest can spiral. In 2011, Thomas was trying to help her grandson’s friend who needed a place to stay. He gardened for her and they ate meals together. Then one day police walked into her home, found a bag of weed, and arrested her.

Her grandson’s friend turned out to be a confidential informant. During the raid, the cops took $350 from her wallet and coat pocket, claiming the money was evidence of drug dealing, according to the report. They then charged the her with possession other than for “personal use,” a felony. Scared of jail, the grandmother quickly pleaded guilty. But as result of her arrest, she had to spend thousands in legal costs.

A year into her probation, she found herself trapped with $2,000 of court debt. But she struggled to get to her midnight shift at a halfway house because her driver’s license had been suspended as a result of her conviction. At the same time, she developed breast cancer. All these factors drove her to drinking, which resulted in a public intoxication misdemeanor in 2013. After these years of struggle, Thomas’s situation has stabilized somewhat, though it has changed irreparably. She now lives in Tuscaloosa, taking care of her son, who has special needs. She says she has forgiven the man who gave her up to the police.

In the last two decades, the public’s opinions on marijuana legalization have swung significantly. Thirteen states, including neighboring Mississippi, have decriminalized small-scale possession, and nine states and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational use. Yet despite polls showing that many Alabama residents across the political spectrum support legalization,the state’s Republican lawmakers have consistently halteddecriminalization efforts.

Unlike in other states, Alabama cities and municipalities lack home rule powers, and cannot enact such changes without approval from the state legislature.

But one set of local officials could drastically slow down the marijuana criminalization cycle: prosecutors. Across the country, from Philadelphia to Houston to St. Louis, prosecutors with reform agendas have stopped or promised to stop pursuing most marijuana possession charges. Advocates hope to add Jefferson County, home to over half a million people in Birmingham and its surrounding communities, to that list.

In November, Jefferson County will elect its next district attorney. The race pits two employees from the Jefferson County district attorney’s office against each other. Mike Anderton, a Republican who was appointedinterim district attorney last year, has made clear he wants to continue prosecuting residents for possession, claiming that he will choose to prosecute those cases as long as the state labels such conduct criminal.

“We prosecute those cases that the legislature designates as criminal offenses. If the legislature passes it, like I said before, if they pass it, we’re going to enforce it, we’re going to do it right and we’re going to follow what the law says,” Anderton told a local TV station last week.

Danny Carr, the Democratic DA candidate, has taken a more reform oriented position and has acknowledged the racial disparities in such arrests, but has stopped short of saying publicly that he will decline to prosecute such cases altogether. In a tweet this month, Carr said “it’s hard to imagine that our limited resources should be devoted to jailing individuals for marijuana possession instead of focusing on serious violent crimes.”

Advocates, like the ACLU of Alabama, have cautiously praised Carr’s comments, and stated that they hope he goes even further, if elected, by choosing to not prosecute those caught possessing drug paraphernalia or one ounce or less of marijuana. In a statement published this week, Dillon Nettles, ACLU of Alabama’s policy analyst, said, “While we appreciate Mr. Carr’s public statement in support of marijuana reform, we also hope to see him continue to clarify how he intends to implement this policy.”

Neither candidate responded to The Appeal’s request for comment on whether they would decline to prosecute marijuana possession cases.

Foregoing such cases could help police and prosecutors better allocate their resources toward more serious crimes, the report notes. In 2016, for example, Alabama police arrested more people for marijuana possession than for robbery, despite the fact that only 1,314 people were arrested for robbery out of 4,557 reported incidents that year.

The researchers also found that these arrests are clogging up the state’s ability to efficiently process forensic evidence in criminal investigations. As of March of this year, Alabama’s Department of Forensic Sciences was juggling roughly 10,000 backlogged marijuana cases and 1,121 forensic biology/DNA cases, which included around 550 “crimes against persons” cases such as homicide, sexual assault, and robbery.

Declining to take on such cases would prevent long-term harm to Alabama residents, like Wesley Shelton, the man who was arrested on a park bench for $10 worth of marijuana. “Right now, in my life, because of that 15 months, I feel as though I’m 10 years behind where I’m supposed to be,” he told the researchers.