By Bob Blalock

Alabama NewsCenter

When Anthony Ray Hinton walked free from death row in April 2015 after spending almost 30 years trapped in a 5-by-7-foot cell, family and friends engulfed him in hugs.

“The sun does shine,” he said outside the Jefferson County Jail, where he had been held awaiting a new trial as a result of a U.S. Supreme Court ruling. Instead, prosecutors dropped all charges against Hinton.

For three decades, the sun did not shine for Hinton, literally or figuratively. At Holman Prison, Hinton never saw much sunshine, being allowed outside in a cage for only minutes each day.

Hinton will be one of many featured speaks April 26-27 when the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration will open to the public. The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) is hosting a series of events to celebrate the opening of its two new institutions.

Hinton will speak during a discussion on April 27 at 1 p.m. on Reforming Criminal Justice in America.

During his years on death row, Hinton suffered through the darkness of defeat after defeat as courts refused to accept his argument of innocence, as guards marched 54 men past his cell to their deaths in the execution chamber 30 feet away and, most devastatingly, when his beloved mother, Buhlar Hinton, died.

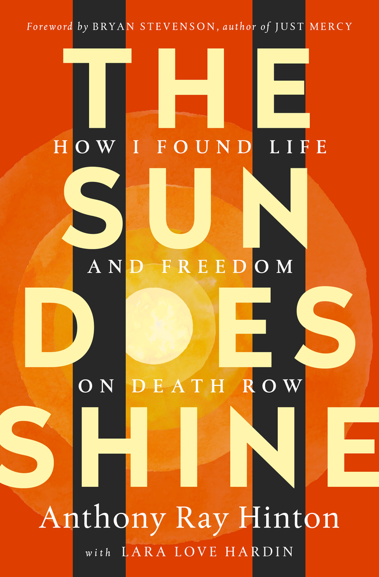

Now, Hinton shares his story in his new book, “The Sun Does Shine.” Relying on his death row experiences and thousands of pages of court transcripts and documents, Hinton writes a first-person account with help from author Lara Love Hardin of the case that handed him a death sentence.

Last month, Hinton and Bryan Stevenson, his lawyer for about two decades, celebrated the book’s release at a sold-out launch party at the old Federal Reserve Building in Birmingham. Stevenson, who carried Hinton’s case to the U.S. Supreme Court, interviewed Hinton at the event put on by the Alabama Booksmith in Homewood.

Stevenson is founder and executive director of the EJI, headquartered in Montgomery, which litigates on behalf of condemned prisoners, juvenile offenders, people wrongly convicted or charged with violent crimes, and others whose trials are marked by racial bias or prosecutorial misconduct.

‘Something Of A Miracle’

“His story is one of forgiveness, friendship and triumph. It is situated amid racism, poverty and an unreliable criminal justice system,” Stevenson writes in the foreword to Hinton’s book. “Mr. Hinton presents the narrative of a condemned man shaped by a painful and torturous journey around the gates of death, who nonetheless remains hopeful, forgiving and faithful.

“This book is something of a miracle, because there were many moments when I believe both of us feared he would never survive to tell his story. We should be grateful that he did survive, because his witness, his life, his journey is an unforgettable inspiration,” Stevenson writes.

In 1985, two Birmingham-area fast-food restaurant managers were shot and killed, but there were no eyewitnesses or physical evidence to the crimes. When a third restaurant manager in Bessemer was shot and wounded, he identified Hinton from a photo lineup, even though Hinton was working at a secured warehouse 15 miles away on the night of the shooting.

Police had recovered six slugs from the crime scenes and the state forensics department matched them to a rusty .38 special that detectives took from Hinton‘s mother’s home, where he lived. Hinton was charged with two counts of capital murder. He maintained his innocence and passed a lie detector test before the trial.

Hinton was convicted based largely on the state forensics employees’ assertion that Mrs. Hinton’s gun had fired the bullets. Hinton’s lawyer had hired a civil engineer as a ballistics ‘‘expert“ and the prosecutor shredded him on cross-examination to the point that Hinton said he knew he was doomed.

Hope

In his book, Hinton recounts the trial and the appeals, and how he somehow managed to survive death row, and even to forgive the people who sent and kept him there. His survival wouldn’t have happened without a vivid imagination, a sense of humor and, above all, hope.

In his book, Hinton recounts the trial and the appeals, and how he somehow managed to survive death row, and even to forgive the people who sent and kept him there. His survival wouldn’t have happened without a vivid imagination, a sense of humor and, above all, hope.

The first three years at Holman, though, Hinton was so angry and filled with despair at his conviction that he spoke to no one – no other inmates or guards – except his mother, his best friend, Lester, and Lester’s mother, who visited every Friday. One night, though, he heard low, guttural sobs from an inmate in a nearby cell.

“Despair was a choice. Hatred was a choice. Anger was a choice. I still had choices, and that knowledge rocked me,“ Hinton writes. “I could choose to give up or to hang on. Hope was a choice. Faith was a choice. And more than anything else, love was a choice. Compassion was a choice.“

Hinton asked the inmate what was wrong and learned that his mother had died that day. Hinton told him: “Now you have someone in heaven who’s going to argue your case before God.“ Hinton decided then that spending his days waiting to die was no way to live.

He began leaving his cell in his mind, to pass time but also to help maintain his sanity. Hinton flew to England to visit Buckingham Palace and have tea with the queen, he ate dinner with the most beautiful women in the world, he won Wimbledon five times, the New York Yankees recruited him to play baseball, he married actress Halle Berry, but then divorced her to marry Sandra Bullock.

Hinton made friends with other inmates and with the guards, and persuaded the warden to allow inmates to form a book club.

“We weren’t the scum of the Earth, the lowest of the low, the forgotten and abandoned men who were sitting in a dark corner of hell waiting for their turn to walk to the electric chair,” Hinton writes.

Locked away from his real family, Hinton realized the inmates on death row were family. An inmate named Henry became Hinton’s best friend, and it wasn’t until later that Hinton found out Henry was the notorious Henry Hays, a Ku Klux Klansman convicted of lynching a black teenager in Mobile.

“We weren’t a collection of innocent victims,” Hinton writes. “Many of the guys I laughed with had raped women and murdered children and sliced innocent people up for the fun of it or because they were high on drugs or desperate for money and never thought beyond the next moment. The outside world called them monsters. They called all of us monsters. But I didn’t know any monsters on the row.”

Years Mount

The years mounted and Hinton’s appeals went nowhere. After he had been on death row nearly a dozen years, his lawyer at the time, who had represented him for more than seven years, visited and told Hinton he was working on a deal with the state to get the inmate life without parole. Hinton refused and fired him. “I’d rather die for the truth than live a lie. I’m not agreeing to life without parole. I’ll rot and die in here before I agree to that.”

Hinton had heard about Stevenson, whose name was well known on Alabama’s death row. He wrote and called the lawyer, who had gained notoriety (and a MacArthur “Genius” Grant) for freeing a man from death row because he was innocent. Stevenson took Hinton’s case. When Hinton was convicted in Jefferson County in late 1986, he told the courtroom “that someday God was going to open my case again.”

He just didn’t know it would take a dozen years. “Because today, God sent me his best lawyer. Today is the day that God opened up my case.”

The fight to prove Hinton’s innocence was nowhere near over. Stevenson hired three nationally recognized forensics experts who disputed the crucial trial testimony of state forensics employees that helped to convict Hinton. They testified in a 2002 hearing that they could not match the six bullets recovered from the crime scenes to a single gun, nor could they match the Hinton weapon to any of the bullets.

A few months later, in September 2002, Hinton’s world was rocked when his mother died.

“There was no hope. There was no love. My life was over,” Hinton writes. “There was nothing left inside me to keep me going. I didn’t want to live. I didn’t deserve to live. I didn’t have the strength to live. They had won, and I was OK with that. I was ready to go.”

‘The Sun Does Shine’

Hinton sat in his cell and considered hanging himself with his bedsheet. Hearing his mother’s voice tell him it wasn’t his time to die, that he had “to prove to them that my baby is no killer,” brought him back from the brink of suicide.

Despite the compelling testimony of the forensics experts hired by Stevenson, Hinton’s string of court losses continued. It took the U.S. Supreme Court to do what state courts wouldn’t. The high court ruled unanimously in February 2014 that he had not received a fair trial because his defense attorney’s performance at trial was “constitutionally deficient.”

The U.S. Supreme Court vacated the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals’ ruling upholding the state court verdict, and the state appellate court sent his case back to Jefferson County. It would take another year, but as Hinton’s retrial approached, prosecutors dropped all charges against him because new forensic testing on Hinton’s gun couldn’t prove the crime scene bullets were fired from the weapon.

On April 3, 2015 – Good Friday – Anthony Ray Hinton walked out of jail to freedom and the loving hugs of sisters, nieces, Lester and Lester’s wife, Sia.

“The sun does shine,” he said. “The sun does shine.”

Anthony Ray Hinton works at the Equal Justice Initiative and shares his story with groups around the country and world.

This story originally appeared on alabamanewscenter.com