By Caroline Preston

The Hechinger Report

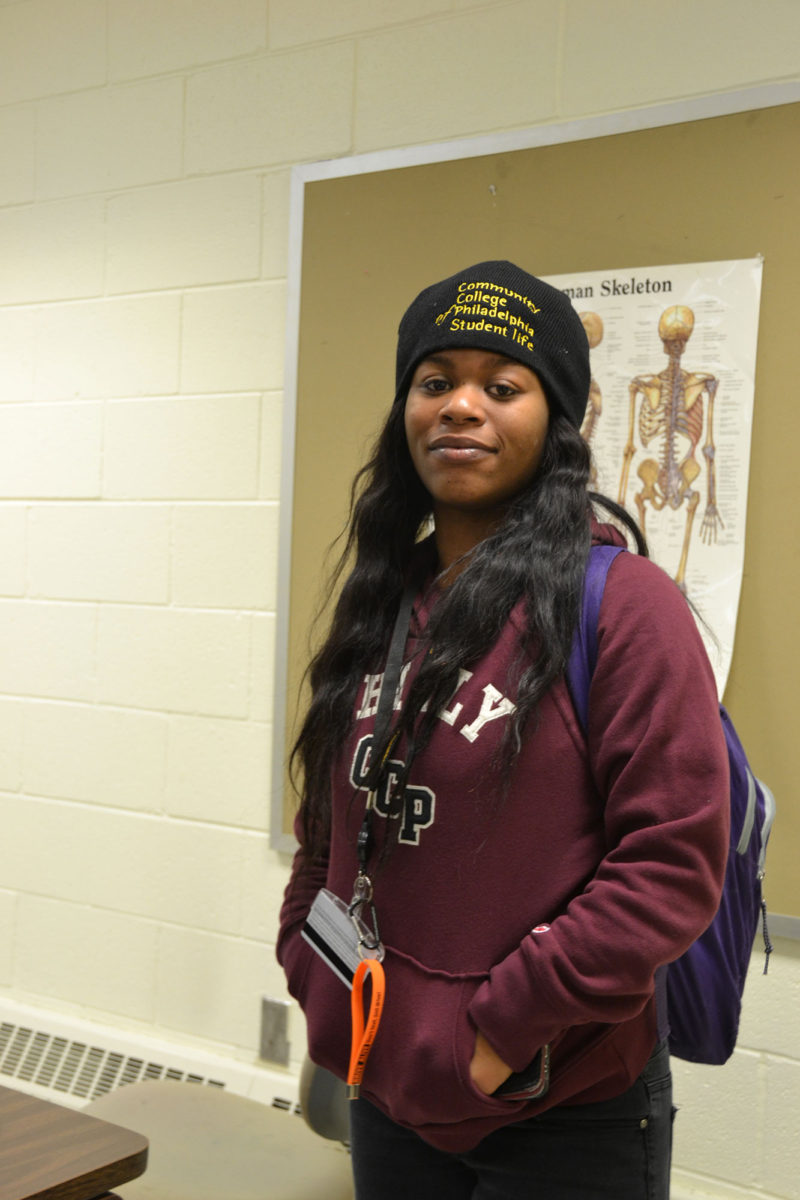

PHILADELPHIA — The Introduction to the Health Care Professions course at Community College of Philadelphia (CCP) is packed with aspiring nurses. There’s the man in his mid-20s who returned to school after years of working low-wage food service jobs. The young woman with glasses who graduated five years ago from a local Catholic high school. The teen who has always loved working with children. The 22-year-old who just earned her GED and wants to follow her two sisters into nursing.

To a person, these students say they want to become nurses to care for others. But they’re also aware that nursing carries the promise of a financially secure future.

Roughly a third of all the jobs the U.S. economy is expected to add over the next decade are in the field of health care and social assistance. The share of Americans ages 65 and older is on track to double by 2060. As the population grays, nurses are poised to become, in the words of the economist Paul Krugman, “the prototypical worker of the 21st century.” Many jobs materializing in health care, such as home health care aides, will pay very little. But a few years of college education can yield big dividends.

Registered nurses, who typically hold two- or four-year degrees in the field and pass a national licensure exam, earn a median of $68,450. In Philadelphia, a medical hub that boasts more than 20 hospitals within 10 miles of the community college campus, registered nurses are paid an average of $72,082.

Nurses may also have greater immunity from the job-destroying creep of automation than some health-care workers. It’s possible that machines could learn to perform the work of radiologists, for example, in the next five years, according to some computer scientists. But because nursing demands interpersonal skills and emotional intelligence, it can’t easily be done by robots, say futurists, medical professionals and technology experts. Instead, the work of nurses may be supercharged by artificial intelligence.

Related: Without changes to education, the future of work will leave more people behind

In his 2015 book “The Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future,” Martin Ford suggests that the spread of A.I. could create a new class of middle-skill health care professionals who use machine learning to supplement their existing knowledge (and perform more of the work that’s done today by doctors).

But the path to nursing isn’t easy — and already technological advances are making it tougher. Many high-school graduates haven’t acquired the critical thinking and math skills necessary to train for nursing jobs, educators say. As the delivery of care grows more complex and data-driven, and A.I. begins to augment the job, colleges will need to continually update their training and work more closely with high schools to pave pathways to the field.

“There’s a huge gap in understanding among guidance counselors about what nurses do,” said Janet Haebler, a senior associate director at the American Nurses Association and a former community college instructor. “Many don’t understand the basics that need to be built early on,” she said. “It does require a heavy background in math and science.” It also entails critical thinking and data analysis.

Nursing students’ math skills don’t add up

Philadelphia and other big cities are ground zero for a national push to require nurses to complete more training. In 2010, the Institute of Medicine and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation issued an influential report calling for 80 percent of nurses to hold bachelor’s degrees by 2020. While CCP graduates can typically find registered nursing jobs at long-term care facilities and other non-hospital settings, many hospital RN positions demand a baccalaureate. Some community colleges have inked agreements with universities so that nurses can earn a bachelor’s (or even a master’s) at lower cost without leaving their campus.

But simply completing a two-year degree is a challenge for many. Before entering CCP’s nursing program, students must pass intermediate-level algebra. But that’s easier said than done: At least 65 percent of all new students, campus wide, arrive unprepared for that course and must first take remedial math, school officials said. Each semester after they enroll in nursing, students take a math competency test, covering relatively basic topics such as converting milligrams to grams. This past semester, only half of the 120 students in their first year of the nursing program passed.

For students who’ve taken years off before college, adjusting to the academics tends to be particularly difficult.

When Laquon Jackson graduated from John Bartram High School in Southwest Philadelphia, he was a tall, amiable teen who liked biology and math but didn’t take his studies too seriously. That was nine years ago. Since then, Jackson has held jobs in food service and studied briefly at Delaware County Community College before family turmoil caused him to drop out. But after he supported his father through a terminal illness, Jackson re-enrolled in school at CCP. He intends to become a nurse, he said, because he “wants to be that person who really takes care of other people.”

Jackson, 26, is two years above the median age for CCP students, and he’s been a little nervous about the digital skills now required. His high school math courses practically feel like another lifetime ago. At CCP, Jackson placed into a remedial course that will require him to pass three semesters of math.

Laura Davidson, an associate professor of dietetics and allied health, said many new students simply lack the confidence to puzzle through math problems. “They’ve had not just bad experiences but in some cases traumatic experiences around math,” she said. “They’ve been taught that they just can’t do it and you have to start telling them, Yes, you can.”

The college started working last year with nearby Universal Audenried Charter High School to introduce its students to in-demand health care skills at a younger age. As part of the dual-enrollment program, this semester high-school seniors take a medical terminology course on CCP’s campus. In addition, the community college recently tweaked its Introduction to the Health Care Professions course to give its own first-year students a clearer sense of the paths to health-care occupations. Now, besides learning the basics of how to communicate with patients, evaluate privacy issues and use medical terminology, students are exposed to a range of health care occupations (dental hygienist, medical assistant and medical technologist among them) and must prepare a plan for how to get there.

“Sometimes people have unrealistic expectations,” said Deborah Rossi, head of the allied health department. “They might want to be a nurse but don’t really want to see blood.” Barbara McLaughlin, who chairs the department of nursing, said the new course has made a difference: “We’re starting to see a group of people with at least one leg up.”

Is empathy robot-proof?

The retooling at CCP offers just a hint of the changes coming to nursing education. Joan Stanley, chief academic officer with the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, said her group recently started a task force to explore updating nursing education to allow students to stay on track as the field changes direction to include more integrated care across health disciplines, a greater focus on the social factors behind illness, treatment in non-hospital settings, and technological advances. “We need to start now to emphasize these new areas of practice,” she said, “the use of big data, the use of A.I. programs to improve outcomes and diagnosis.”

At present, such uses for A.I. are only beginning to take shape, and so far some of the most advanced examples are happening abroad. At London’s Royal Free Hospital, an app called Streams, developed by the Google-financed company DeepMind, is helping to quickly detect when patients are experiencing kidney failure and alert nurses to these emergencies. DeepMind is researching ways that A.I. could be used to improve diagnostics in the future. For example, the company is working with an eye hospital in London to investigate how machines could be trained to interpret eye scans and detect eye disease. With this faster, more sophisticated means of diagnosis, nurses could spend additional time communicating with patients and working with them on treatment plans.

“This is health care for the fourth industrial revolution,” said Benjamin Pring, co-founder of the Center for the Future of Work at technology company Cognizant, which released a report in November identifying “AI-assisted health care technician” among 21 “jobs of the future.” In a future envisioned by Cognizant, “in-depth patient care and diagnosis is no longer the preserve of doctors with seven years of qualifications.”

Still, all this was far from the minds of CCP students as they sat down one recent Friday for the second “intro to allied health” class. Inside a windowless classroom, Jackson asked his professor for help navigating the school’s computer network. It was the second class of the semester, and many of the students were just getting acquainted with the basics of campus life.

Although concerned about the math, Jackson was less worried about the communications skills nursing entails. Some of his previous jobs were in hospitals, where he chatted with patients while serving meals bedside. “Some people don’t have family come visit,” he said. “We’re their family. We get to know them and show them there is someone who cares about them.”

So far the nursing career path is working for Jessica Maguire. While attending CCP, she received food stamps, but now she’s earning wages that lift her well above the poverty line. Last summer, after completing the college’s nursing program, she found a job at a rehabilitation facility, working the night shift and earning more than $30 per hour.

While at CCP, Maguire saw her nursing cohort dwindle from some 100 students to around 65. “It’s more about critical thinking than regurgitating information and some people can’t make that shift quickly enough,” she said. But now that Maguire has passed the licensing exam and become a nurse, she plans to keep going. She is currently enrolled at West Chester University, just west of Philadelphia, for her bachelor’s. “The goal is to move up and go further,” she said, “maybe into management, maybe get a master’s.”