By Solomon Crenshaw Jr.

For the Birmingham Times

Ervin Swain sat on a blue bench outside the fourth-floor elevator in the parking deck of the Birmingham Veterans Affairs (VA) Clinic. The 62-year-old Army veteran from Talladega needed a break from standing because he’s still getting used to the prosthetic left leg he got from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

“It’s been pretty good, pretty good,” he said of the care he’s received from VA. “They helped me out a lot. I got sick and they put me in the hospital. They operated, and I got a prosthetic that costs a lot of money. They did alright by me.”

Veterans Day, observed annually on Nov. 11, honors military veterans and those who served in the United States Armed Forces.

Healing

“To care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow, and his orphan.”

These words from Abraham Lincoln’s second Inaugural Address in 1865 were spoken to a bruised nation still reeling in the aftermath of the Civil War. While addressing the need to heal the country, the 16th president of the United States specifically pointed out the national responsibility to doctor, nurse, and minister to those who served to defend it.

‘I Care’

But Lincoln couldn’t envision the scope of today’s VA.

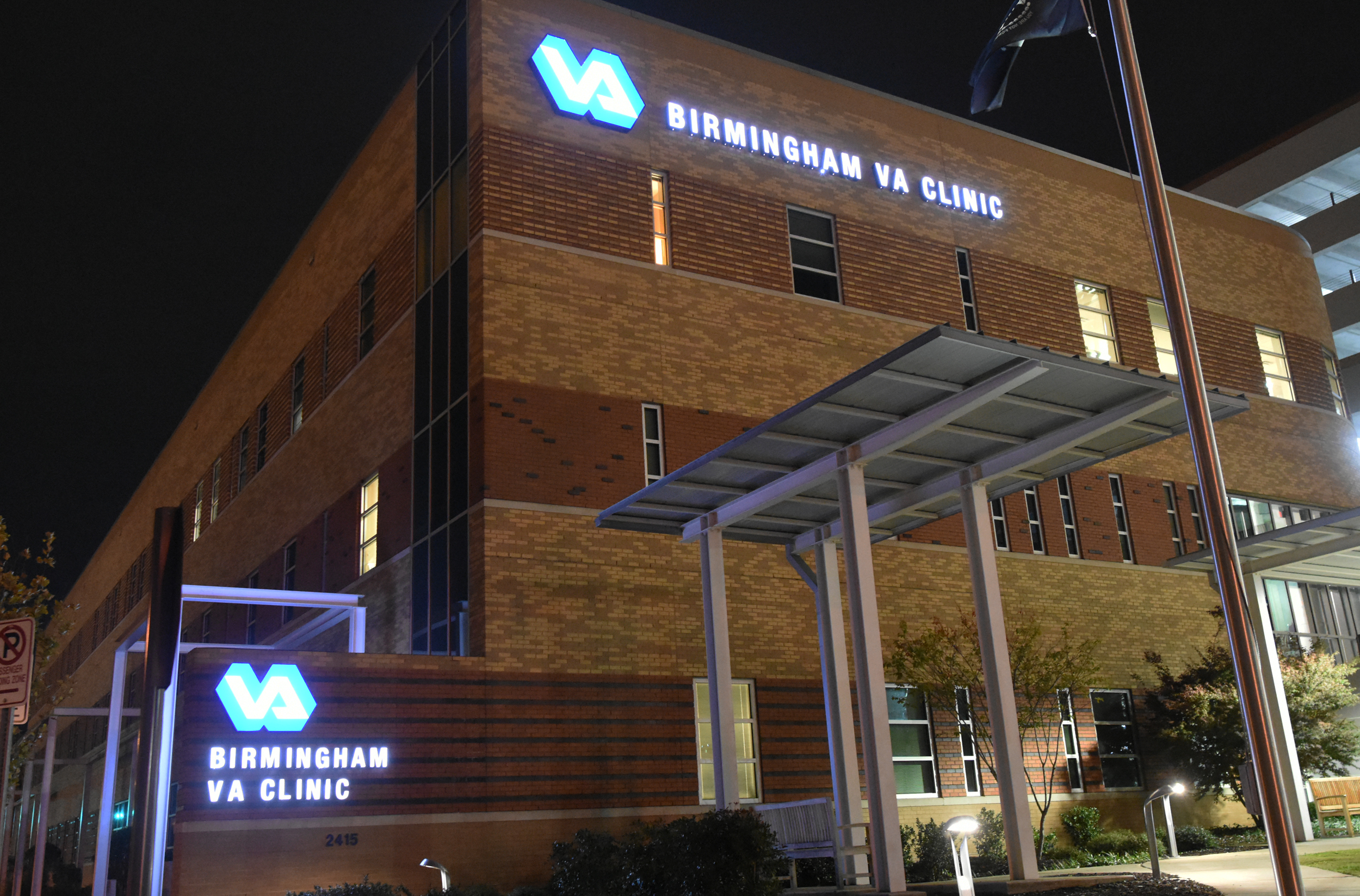

The Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center (BVAMC) serves men and women who have been in the various branches of the armed forces. Now, as one walks the floors of the VA Medical Center on University Boulevard on Birmingham’s Southside or the new clinic building five blocks east at Seventh Avenue South and 24th Street, a simpler motto can be seen on lapel pins: “I Care.” That is the VA mission today—to care for veterans, male and female, and their families.

“There are probably 300 or 400 services, … everything you can think of, from primary care to mental health services, as well as almost 200 specialty health services,” said Birmingham VA Public Affairs Officer Jeffrey Hester.

The clinic, for example, serves veterans in the areas of audiology, prosthetics, women’s health, physical therapy, and rehabilitation. Plus, it includes a lab and pharmacy and provides radiology services.

Serving More Than 65,000

The BVAMC (formerly the Birmingham Veterans Administration Medical Center) opened in 1953 and currently serves more than 65,000 veterans in 24 counties, including Jefferson, Shelby, Blount, Etowah, Madison, St. Clair, and Talladega.

“Last year, we conducted about 850,000 outpatient visits and provided services to about 67,000 veterans; some of them we might see 50 times, some of them we might see one time,” Hester said. “We typically have 6,000 to 6,200 inpatient visits, and we have many emergency room visits and many mental health visits, many patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).”

A recent tour of the BVAMC—now known as the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center — and the Birmingham VA Clinic provided a glimpse of the various services the facility provides and the efforts made to provide them.

“We will do all we can do to help,” said Ronald E. Agee, chief of benefits and eligibility coordinator. “I want to work as hard as I can to get you into the VA system, but at the same time I take care of the greater system. If you’re eligible to get something, we’re going to push as hard as we can to get that for you. If you’re not eligible for it, we’re not going to break the law, but we will tell you what you need to do to fix your situation.”

‘Leg or Die’

Talladega Army Vet Swain comes to the Birmingham VA Clinic twice a week as he undergoes therapy to walk without a cane. The 62-year-old amputee had coronary artery disease, a condition that caused his veins to shrink after an accident he had years ago.

“It was the leg or die, so you take the leg,” he said with a laugh.

The care provided by VA extends beyond physical and mental support. For some veterans, it even includes ensuring that they have a place to live.

Finding Homes

VA Homeless Program Coordinator Willie Fields said he’s seen homelessness among veterans decrease in his 34 years with VA.

“Especially in Birmingham,” he said. “We go by a PIT, a Point-in-Time survey, which is conducted every year. In the last PIT, we could find only two homeless veterans who were living on the street in places that were not meant for human habitation.”

VA has 606 housing vouchers to get veterans into leasing agreements. Each year, the benchmark is 92 percent; this year, 94 percent of those vouchers were doled out. Those numbers were helped by Operation Reveille, a one-day, one-stop-shop that took chronically homeless veterans off the street and placed them into their own homes. That event was conducted twice in 2017.

“The major challenge we’re going to have now is maintenance,” Fields said. “We have demonstrated that we can get people leased up. The challenge now is to keep them housed. We have to do that through case management.”

The issues that lead a veteran to homelessness are not eliminated by simply putting that veteran into a residence, Fields said. Factors also include domestic issues and financial matters. The aim now is to reduce the number of “negative exits,” incidents such as a veteran who won’t pay rent, abandons an apartment, or is evicted by a landlord or the public housing authority for rules violations, Fields said.

“If our guys don’t abide by those rules, [public housing and landlords] do initiate eviction procedures,” he said.

Palliative Care

VA also offers services for something many may not want to talk about: death.

That’s where Palliative Care Nurse Practitioner Alfreida Hogan and others in the VA’s Safe Harbor unit come in. They help veterans and their families prepare for death.

Michael Johnson, a doctor of pharmacy in Safe Harbor, is often seen wearing rows of badges on his lab coat from his 43 years of Navy service, having been deployed with the Marine Corps, Army, and Air Force. He’s worked with VA for more than 30 years and has been with Safe Harbor for seven.

“They had to talk me into coming. Then I found out this is probably where I should have been,” the Woodlawn High School and Samford University alumnus said, acknowledging that he had unresolved issues from his own loss. “It provided healing when my father died. I was able to heal myself by coming up here and helping others deal with what they were going through.”

The walls of the sixth-floor unit are decorated with pictures of water and boats, putting one in a mindset of a journey over a peaceful horizon.

“There are times where patients get to the point where we have done all we can, and we can’t heal that broken body,” Hogan said. “When they get to the point that they say, ‘I know I’m dying, and I know there’s no cure and there’s nothing else we can do,’ we say, ‘Yes, there is.’”

Hogan’s voice fell to almost a whisper as she continued.

“We can comfort . . . it’s not just them; it’s the whole family.”

Hogan always travels with Kleenex in her pocket.

“That’s my tool,” she said. “You listen to them cry. You listen to them talk. Sometimes all you have to do is listen.”

And provide a shoulder on which to lean.

“It’s not like a job,” she said. “It’s a mission.”