By Je’Don Holloway Talley

For the Birmingham Times

It takes a village to raise a child—and it took a pastor, parents, and a pair of community activists to help establish at the Black Star Academy Home School Co-Op in 2015.

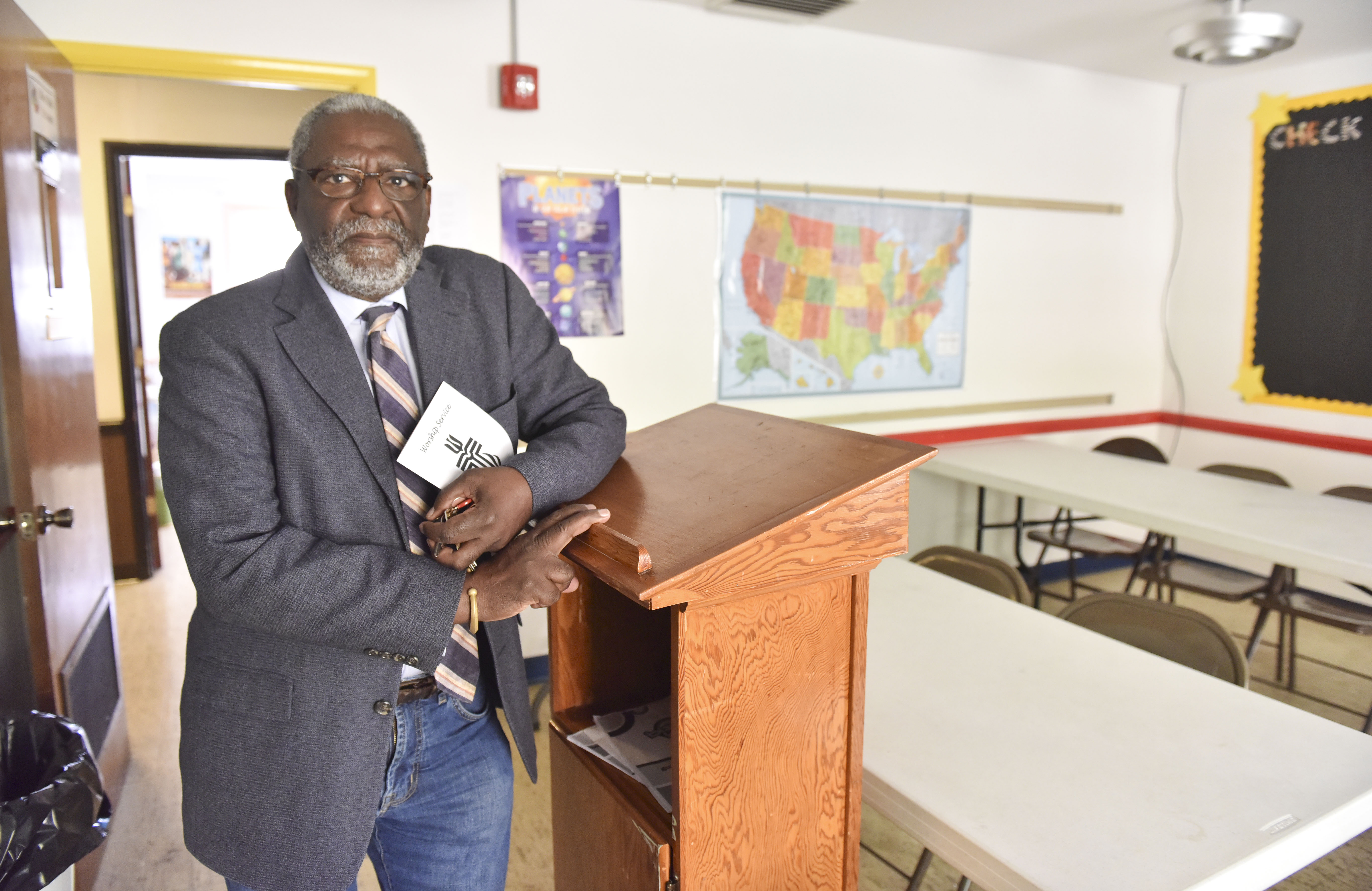

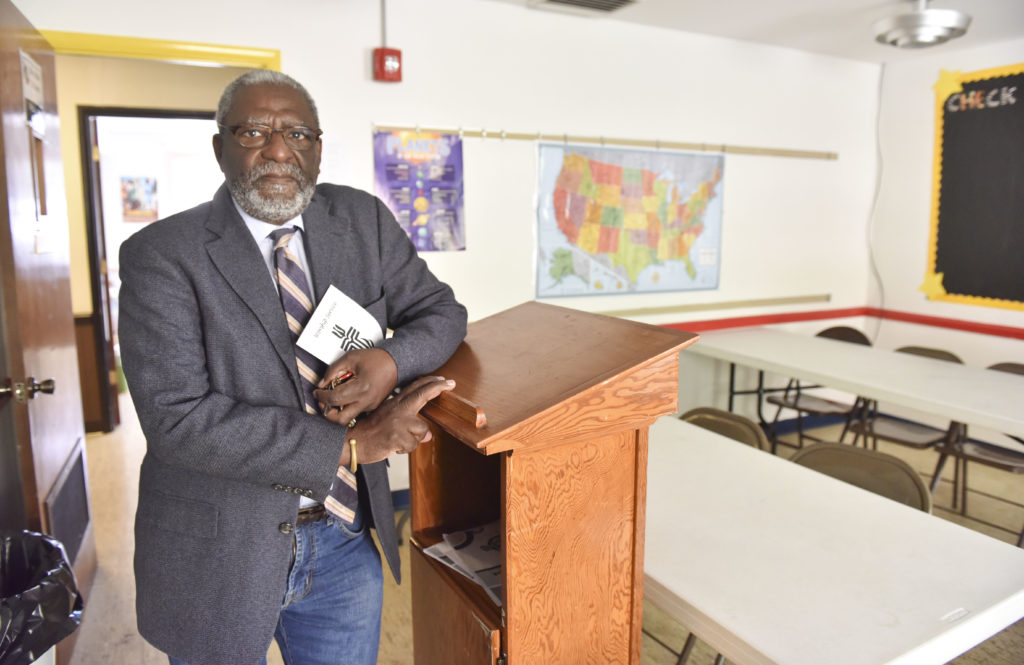

Tremon and April Muhammad are the founders of the Black Star Academy (BSA), believed to be one of the first culturally centered home schooling collectives in the state. While the academy has been functioning as a collective since 2009, it expanded with involvement from the Rev. James Ephraim, pastor at First United Presbyterian Church in Forestdale and community activists Thomas “Divine Mind” Davis, founder of the African-centered One House group, and Bennie Holmes.

“In 2014, I was promoting One House Freedom School interest meetings on Facebook, and a friend sent me a [direct message] about the Muhammads, who had been doing the same thing for more than 10 years,” Davis said. “We wanted to have a self-sufficient educational system that would equip children who look like us with the best possible chances of creating jobs for themselves and for the community.”

Davis had studied patterns of public schools, and his One House focus group “decided that building a curriculum for a Freedom School would be the best way to prepare our children for the future.”

“… Not only do we want them to be taught an accurate history lesson,” he said. “We also want them to learn things like agriculture, mechanics, sewing, martial arts, and more.”

Startup Institution

What began with a conversation led Davis to assemble people who felt an institute with an African-centered focus was needed.

“We scheduled a few One House meetings, and I asked [attendees] what needed to be addressed most in our community,” he said. “Education was stated, so from that point on I said we would create a Freedom School.”

In preliminary meetings, the school’s curriculum and mission were created.

Davis’s idea resonated with Holmes: “I was on board from the start because I’ve always favored the idea of educating our children, black children, independently of the traditional school system. I immediately wanted to know, ‘Where can I fit in?’ I wanted to know what we needed to do to actually make this happen.”

Holmes, who was one of the driving factors in Ephraim’s decision to move forward with the startup institution, had already been doing research and weighing the pros and cons of Alabama Charter Schools when he saw the best opportunity in starting a home schooling collective. Holmes’s involvement attracted Ephraim, whose long-time interest in Afrocentrism drew him to the One House mission.

“Looking at my own particular background, my life centered around school and church,” Ephraim said. “And here I had [the church], so [I said] let’s look at how we can develop this Afrocentric idea into an educational institute. A year, maybe six months later, [Davis] suggested that [April Muhammad] and I should talk to see what it would look like if we started a school. Since she already had a group of home-schoolers, we started with them.”

Finding a Home

The 2014 meeting with April Muhammad went well, and they decided to merge. By January 2015, the home schooling collective opened inside the Muhammad’s home. By the fall of 2016, they moved to First United Presbyterian Church.

“We realized that we needed a place where kids, parents, and the community could come and learn as a collective,” Ephraim said. “We are laying the foundation for building communities and working with the African concept that it takes a village to raise a child, and we realized we don’t have the village. In order to create the village, the parents and the community need to be involved.”

“Home schooling gave us the advantage because parents are intricately involved and ultimately responsible for their child’s education. It offers an opportunity to engage in a new understanding of what school is all about,” he said. “You can’t do that with a traditional school [because] the parents aren’t involved like that.”

Accountability

Ephraim said there’s more accountability “among parents, students, and teachers. If something is wrong, someone will notice and be there to support. It’s a community. We’re taking the life experience itself and letting it be a teaching moment. It’s beyond a textbook.”

What impresses Ephraim most is that the students are receptive.

“We’re not dealing with fights, fussing, and carrying on. We’re dealing with students who are eager and excited,” he said. “We have our challenges but, from the students to the teachers to the parents, there’s accountability for everyone engaged in the process. We give special love and care because we care about the whole person.

“We’ve been at this for a year and a half or so, and I’ve seen that kids come in with excitement in their eyes. They’re engaged in the learning process like I’ve never seen before.”