By Nick Patterson

The Birmingham Times

When we think of violence, we often think of acts committed by one person against another. But in Alabama, the deadliest acts – in terms of numbers of lives lost — are committed by people against themselves.

Educating people about the striking realities of suicide is the mission of ASPARC, the Alabama Suicide Prevention and Resources Coalition. This small nonprofit has taken a big role in teaching individuals, corporate groups, educational institutions, doctors, first responders and religious congregations to recognize the signs of suicidal thinking, and how to successfully intervene.

September is National Suicide Prevention Month, but few realize how big a problem suicide really is. Consider a few facts:

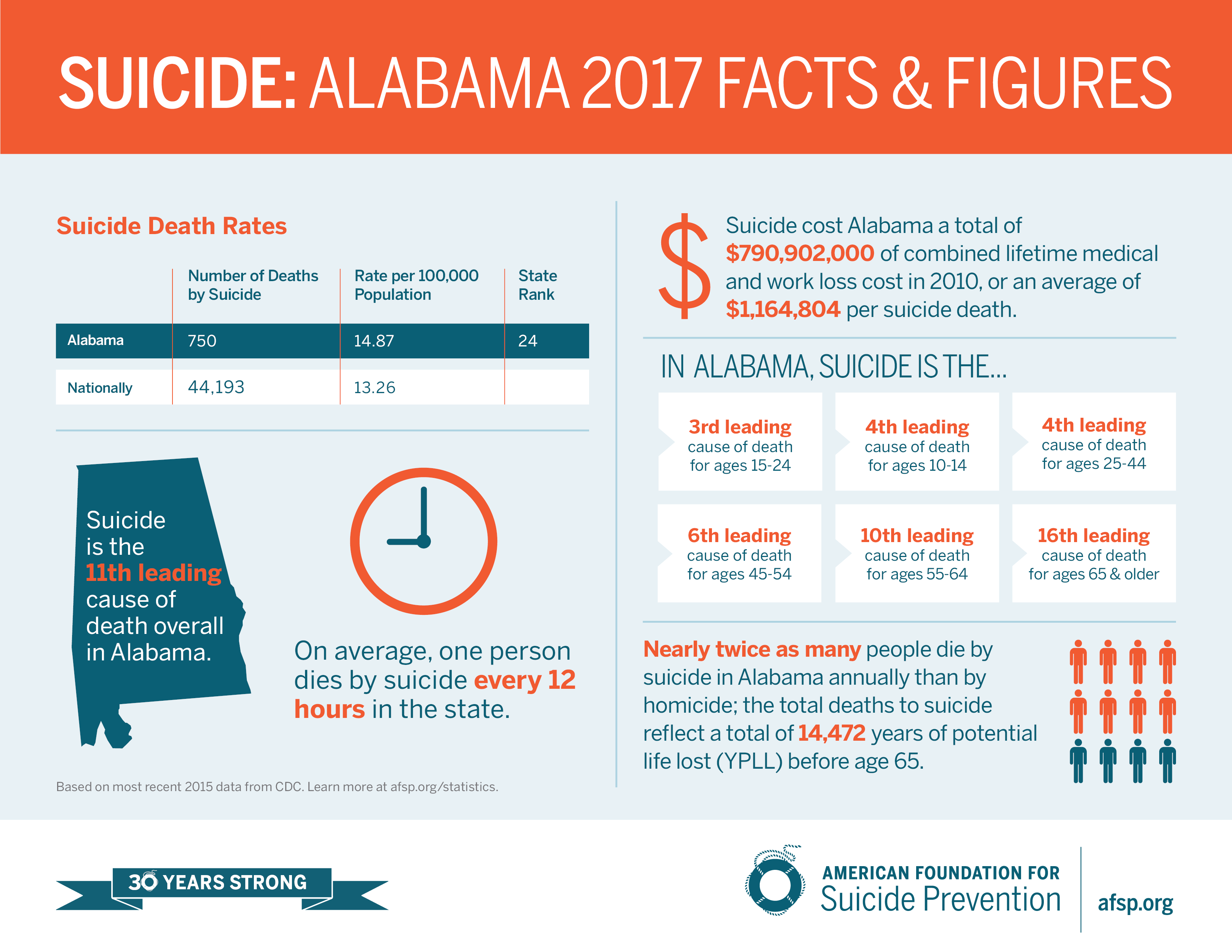

- Suicide regularly takes more lives than homicide, and not just in this state, but across the country.

- Alabama has one of the highest suicide rates in the country, about 14.87 suicides per 100,000 people in 2015.

- Fifty percent of those who kill themselves in the U.S. use a gun, while in Alabama, that number jumps to 68 percent.

- Many people who kill themselves have tried unsuccessfully before.

- People can be talked out of suicide.

The idea that suicide is preventable is hard for some to believe, but it happens every day.

“It’s preventable, and there’s a stigma that we’re trying to deal with,” said Dr. David Coombs, associate professor emeritus in the Department of Health Behavior at UAB, and president of ASPARC. “We need to train people to recognize and not be afraid to intervene. That’s a barrier. They’re afraid to say something because mental illness is very personal, like asking your income or religion. So that’s what we try to get over.”

The nature of the beast

For people in every age group from 10 to 65, suicide rates are much higher than intentional homicide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for people 15 to 24 years old.

“People are more afraid of homicides,” Coombs said, But the impact of suicide is “tremendous.”

Coombs said that up to 60 relatives and friends are seriously impacted by a suicide death — “in other words, grieving, depression” – and as many as 100 more are affected in lesser ways.

Those who lose loved ones to suicide are at an “elevated risk of suicide themselves,” said Dr. Judith Harrington, past president of ASPARC, and assistant professor of counselor education at the University of Montevallo.

And while the rate of suicide is dropping in some places, not so in Alabama.

“I would say that Alabama has a serious problem,” Coombs said.

In 2015 there were 750 suicides in Alabama, versus 472 homicides. The number of suicides in the state went up more than 2.5 percent from 2011 when there were 640 known suicides. The 2015 suicide rate in Alabama is 14.9 per 100,000, which is higher than the most recently reported U.S. rate of about 13.3 per 100,000,” according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Chronic depression is often at the root of suicide, a problem which is made worse when the economy is bad, or better in some sectors than others, Coombs said. He cited an economist who pointed out that while Alabama has gained thousands of jobs in the automobile industry over the last few years, at the same time, the state has lost many thousands more in the textile industry. That disparity means that while some have work, many do not. Unemployment over the long term can lead to depression, substance abuse, poverty and abuse especially among men, he said.

“Going on welfare, begging to drink, taking drugs, losing a family and a home … they really get very depressed,” he said. “They often become suicidal.”

Coombs said that historically, suicide rates went up during the Great Depression, and that today, a similar pattern of chronic unemployment-leading to depression-leading to suicide plays itself out in parts of the country where jobs are scarce, like “isolated small towns” in the West and small cities where factories close and there is no other good employment. And suicides tend to occur more frequently among some demographic groups, like Native Americans, where men often struggle to get suitable work.

“So there’s no question that economics is a part of this,” Coombs said, adding, “It’s not the only part.”

Beyond chronic depression, other mental disorders including bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia can lead to suicide, as does lack of access to mental health services, and easy access to guns, he said.

What can be done

ASPARC has trained more than 13,000 people to recognize the signs and intervene. Much of their success has been through the use of an “evidence-based curriculum” of a program called QPR, developed at Spokane, Washington’s QPR Institute. QPR stands for “Question, Persuade and Refer” and its goal is to teach people to “recognize suicidal warning signs in others; persuade them to get help; and refer them to appropriate help resources,” according to an ASPARC brochure.

“To me its fashioned a lot like CPR training,” Harrington said. “Just like regular citizens can intervene in a heart attack, they know what to do if they’ve had CPR training. You don’t have to be a mental health professional to do suicide prevention at that stage.

“It’s actually promoted for community groups, clubs, book clubs, Sunday school classes, churches, synagogues,” she said. “We ended up marketing it a lot to mental health agencies that we knew are probably short-staffed and short-funded.”

ASPARC’s training programs also include Lay My Burdens Down, which is designed specifically for faith communities. When they started, reaching out to places of worship was “really uncharted territory,” Coombs said.

“In a place like Alabama where mental health [services are] compromised anyway, the churches are like really central social support systems for people and we wanted to build bridges with faith-based organizations to see if we could get the most modern available information and maybe dispel some of the myths that have been in place for many years about sin and going to hell and stuff like that.”

Like people in general, people in churches have fear about dealing with those who may be suicidal, Coombs said. “You would think they would be equipped to deal with a member who was suicidal but many of them are not… They’re afraid to,” he said. “So we go in and try to destigmatize. People will turn to their pastors like they’ll turn to doctors. They trust them, usually. So we’ll train people in churches.”

Teenagers under stress

Among those needing particular help to deal with suicide are teenagers and their parents. Many youth suicides — contrary to a popular myth — are preventable, Harrington said. “Another myth is that, ‘Well if he’s talking about it he won’t really do it.’ We know that for every completed suicide that person has told at least two people, in 80 percent of the cases, communicated a warning sign of some kind. And those warning signs may be veiled or misunderstood. But there’s this new saying now with terrorism ‘if you see something, say something. ‘And it is very applicable to suicide.

“If something seems off, if that’s not characteristic to that child or that young person, check your gut and do something about it. Just ask the question. Check it out. Tell someone who would know to take care of that young person,” she said, adding that the person you tell could be a counselor, a coach, or a parent, among others.

“Just don’t stop asking for help,” she said.

Parents also need to read up on warning signs and risk factors for possibly suicidal intentions. And when they see the signs, they should not take them lightly, even if the child tries to downplay the seriousness of the situation, she said.

“They’re afraid that they’re going to be deemed crazy or they’ll be in trouble, or they’ll be locked up, or something,” Harrington said. “But if a parent was familiar with the warning signs or the risk factors, they would know [to be alert].”

Learning can save a life

Getting educated about the truths surrounding suicide can make all the difference – that’s a big part of ASPARC’s message.

“Number 1, suicide is preventable, but we need everyone’s help,” Harrington said. “A lot of people think suicide is a rational choice. And it is not. It is a fatal outcome of unbelievable psychological pain. And most people that we have anecdotes on that have attempted suicide and survived that attempt really understood very quickly they didn’t want to die, they just wanted the pain to end.

Suicide, she said, may ultimately be connected to a number of factors. “It is multi-factorial in its cause. but that does include neurological and biochemical context, access or barriers to access to help, and we should take every warning sign seriously.”

#BeThe1To – The Movement

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline started #BeThe1To as a way of using social media to spread the word about suicide prevention, “and show how we can all take action and make an impact in someone’s life.” The idea is that anyone can be the one to save a life. They recommend five basic steps:

- Ask.

- Keep them safe

- Be there.

- Help them connect.

- Follow up.

For more information, visit www.BeThe1To.com

Signs to Watch For

According to ASPARC here are some signs that a person may be contemplating suicide:

- Depression, social isolation, substance abuse

- Giving away prized possessions

- Skipping classes or events

- Sleeping too much or too little

- Expressions like “I’d be better off dead.”

- Feeling hopeless, helpless, or worthless and talking about it

- Drastic changes in behavior

- Has attempted suicide before or has had a family member or close friend commit suicide

For more information about ASPARC or its programs, visit www.ASPARC.org.

For more information about the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, visit www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org