By Stuart Miller

The Hechinger Report

NEWARK, N.J. — Tahiv McGee spent Fridays during his senior year of high school at Rutgers University-Newark, where he worked with faculty and a doctoral student on a psychology research study. McGee, who took seven Advanced Placement (AP) courses during high school, found the experience immensely valuable, even though he plans to study neurology, not psychology, at prestigious Pomona College, in Claremont, California.

This kind of experience may be common at New Jersey’s most selective and wealthiest suburban high schools, but McGee graduated from North Star Academy College Preparatory High School in Newark, where 84 percent of the students are economically disadvantaged and 98 percent are black or Latino. The charter school takes students via lottery and has a slightly higher percentage of economically disadvantaged students than the public schools in this poverty-stricken city.

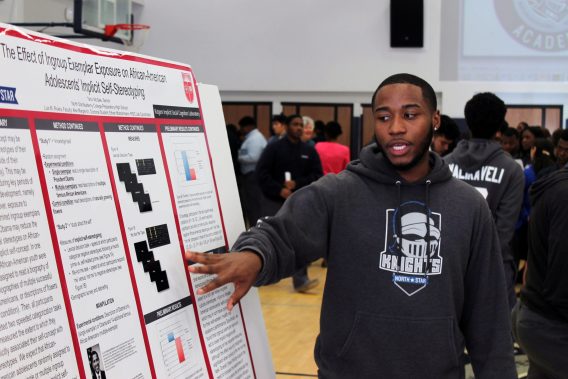

The Rutgers program “helped me get outside of my community,” says McGee, adding that the research project, “The Effect of Ingroup Exemplar Exposure on African-American Adolescents’ Implicit Self-Stereotyping,” explored a topic he had studied for his high school debate team. “I was seeing different perspectives and forging connections I may not have had otherwise. It showed me the potential I could have academically.”

Related: Pathways to jobs of the future opening via summer STEM programs

North Star is part of the Uncommon Schools network, which has elementary, middle and high schools in Newark. According to network statistics, North Star’s high school students vaulted the racial achievement gap by exceeding national averages for SAT scores and the percentage of seniors passing AP exams, and its alumni graduate from college at five times the rate of low-income students nationally — about the same rate as America’s wealthiest students.

Yet for years, students like McGee had limited exposure to the world of STEM, or science, technology, engineering and math. In 2010, the school looked back over the previous six years and saw that just 6 percent of North Star graduates majored in STEM subjects in college. “That number seemed incredibly low,” says principal Michael Mann, adding that with STEM providing so many well-paying jobs, it was imperative to shift gears. Some experts foresee a growth of 10 to 20 percent in STEM-related occupations in the next ten years, with the potential for a shortfall of STEM-trained workers.

“We’re very obsessive about trying to figure out what would best prepare our students for the careers of their choice,” says Syrena Burnam, the school’s science chair, who arrived in 2012. So North Star methodically set about reinventing its approach to STEM, with the experiment yielding positive results— from 2013 through 2015, 33 percent of its alumni majored in STEM disciplines in college.

Like a good STEM student, Mann started by doing his own research project. He studied New Jersey’s highly selective technical and vocational schools, like Bergen County Academies in Hackensack, which offered multiple AP courses and real-life experience working in labs and on research projects.

Unlike students at some suburban schools, North Star students didn’t have parents with connections to research universities or money for in-house equipment. But Mann was willing to improvise, even if it meant changing the rules and the identity of the school. “Our students perform well in most categories, and our level of instruction is better than at other high schools, so we thought we could really do anything if we made the right plan for it,” he says.

Related: High school seniors reveal choices in joyous ‘signing day’ ceremony

North Star added AP Biology in 2011, AP Calculus BC in 2013, AP Computer Science in 2014, AP Chemistry in 2015, and AP Physics last year. This year the school will offer AP Environmental Science, too. Mann revised the school’s rigid graduation requirements to allow students to take more than one AP STEM course at a time.

Students who perform well on AP exams do better in college, according to some research. “The classes are more rigorous and the students work to that level,” Burnam says, adding that AP classes are crucial for North Star students because “there are so many different challenges when they get to college, so if they know they’re okay academically, then it’s easier.”

(She also believes that the school’s unwavering standards, with automatic detention for missed or poorly done assignments, help. Alumni always tell her that the school taught them necessary organization skills and self-discipline, she says, and that they were therefore better prepared for college than other students.)

“The AP classes really expanded our interests and inspired me in figuring out what I want to do when I get to college,” McGee says.

In the North Star AP Computer Science class’ second year, all 14 of its students passed with a score of 3 or higher (nationally, about two in three AP students score a 3 or higher). Of the 39 African-American students in all of New Jersey to pass AP Computer Science, 10 were from North Star. (The other four North Star students who did so are Latino.)

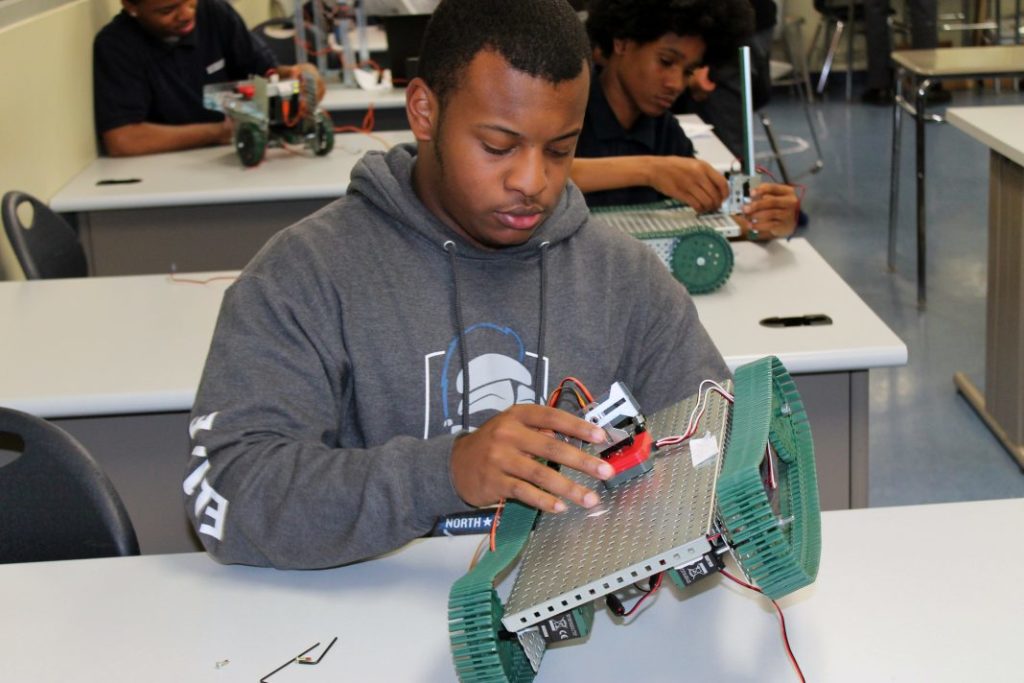

The next step was adding STEM electives. “We are a highly disciplined, very structured school, known for squeezing the minutes, but we had to try and keep that and build in room for project-based learning,” Mann says. He knew that the hands-on experience of project-based learning — in which students focus narrowly on one topic which they explore through a long-term undertaking — is effective, even essential, in STEM, since it reflects the way students will learn in college and graduate school and the way they will eventually work in labs. But he didn’t want the narrowly focused curriculum of some project-based schools, so he set aside two hours each Wednesday for students to explore specific areas in depth — from sound engineering to making a documentary or designing a house. When Mann created an engineering department, nearly half of all freshmen chose engineering as an elective.

“Many of my best math students weren’t choosing what they were best at once they got to high school or college because they didn’t know about STEM or what engineering was,” says Andy Chen, who came to the high school after teaching eighth-grade math. “I want to open their eyes to what is out there. I talk to my freshman about engineering being the highest-paying major.”

Chen proudly shows off pictures on his phone of students who have given up lunch period to work on their projects. This past school year, North Star reports that its students beat peers from 16 schools in a New Jersey STEM competition for Best Design; in the contest, they designed a portable shelter for refugees in Siberia that could retain heat and withstand heavy snowfall. “They show up after school excited to work,” says Chen, who plans to add another engineering course and a robotics team next year.

But the school couldn’t entirely achieve its goals in North Star’s “hermetically sealed bubble,” where all the teachers care deeply and all the students have similar backgrounds. “The students are heading off to the real world, where they are not always welcome, or they’re just excluded,” Mann says. “At college, when class ends, it looks like all the white kids go off and feels like a closed society where there’s a lot of secrets.”

Mann wanted to establish year-long research partnerships to get North Star students onto college campuses, working with white graduate students. “No matter how high their AP scores were, they had a thing in the back of their head that there were limits to what they can do,” he says. Putting them in university labs would help them see that majoring in STEM is “realistic and feasible.”

Related: Unlike the students they oversee, most college presidents are white and male

But when he set out to recruit partners, he found many universities reluctant because they already had relationships with suburban schools, often informally arranged through well-connected parents. “One dean said, ‘We can’t open it up because we’d be overwhelmed with interest,’ ” Mann says.

Mann and Burnam dug in, wooing contacts at several schools. “It was very time-consuming, with heavy work on the relationship building,” Mann says. The social justice angle he pushed — asking “If students of privilege get more privilege, how does that lead to equity?” — won over some department heads. But he found greater success when he learned that the grants on which young researchers rely, from the National Institute of Health and the National Science Foundation, prioritize projects that impact K-12 education. North Star ultimately found partners at Rutgers, Seton Hall, the New Jersey Institute of Technology and the Princeton Plasma Physics Lab.

“These programs do more than just give the students a hands-on experience, they enable these students to picture themselves as part of that community,” says Andrew Moore, dean of the School of Computer Science at Carnegie Mellon University and an advocate for stronger STEM education for economically disadvantaged students. He praises North Star’s approach, especially because he says it can be reproduced across the country.

“It was the first time I worked in a professional setting, and I really valued that,” says recent North Star graduate Gregory Ezike, who worked at the Princeton Plasma Physics Lab and is going to NJIT in the fall. “I was nervous about getting thrown into a project and being expected to produce. You learn to be resourceful and that will be really valuable.”

Hikmah Okoya, who worked with Ezike at Princeton and is going to Bowdoin College this fall, was initially scared, but learned that the graduate students there “were really generous, and would sit you down and help or give you the resources you needed, so over time I became less nervous.”

Tracy Tran, a Rutgers-Newark scientist who hosted North Star students in her biology lab, was so impressed with the students that she organized a five-part series of workshops, calling on her colleagues to cover everything from embryonic development to biodiversity. “I wanted to introduce the students to all the subgroups of biology, and we made it hands-on so they were using microscopes,” Tran says. “I also wanted to make it personal and tell our stories, so when they get to college they might be less hesitant to approach a professor.”

Even North Star students who don’t plan to pursue STEM learn from the research projects. “Learning STEM in high school does not mean you’ll be wearing a white lab coat when you’re 25,” says Moore. “You can be a product manager in theater or education or city planning, and you need to be able to design solutions, use technology and look at data, so you need a basket of skills. We like to see learning by doing because it creates a fearlessness in tackling problems.”

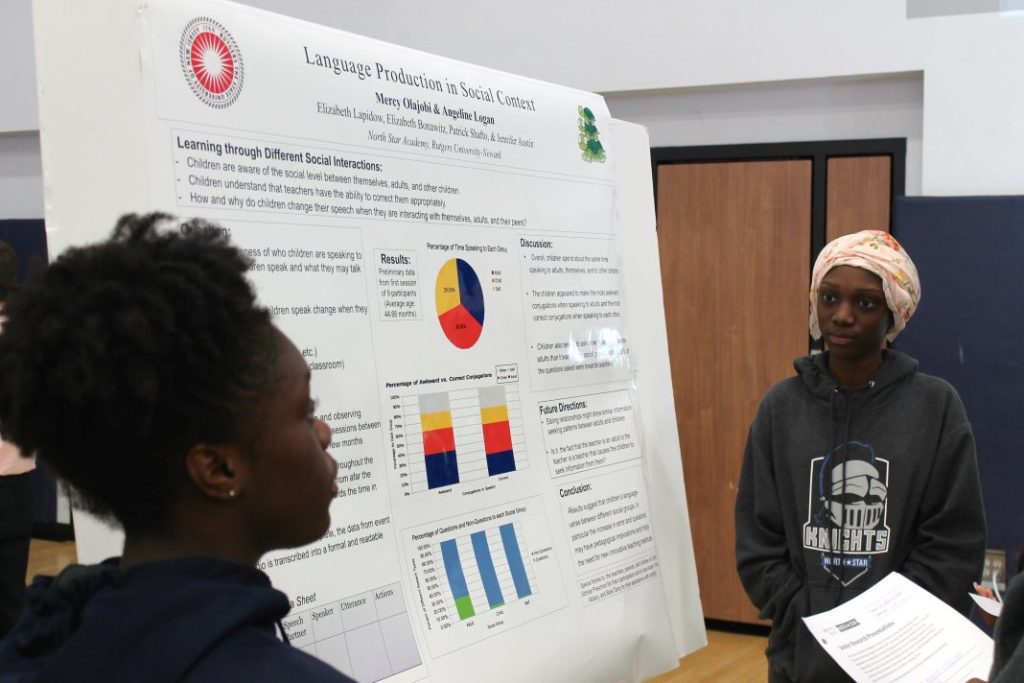

Mercy Olajobi, who plans to study business and theater at Muhlenberg College, worked alongside classmate Angeline Logan, who plans to go into law after attending George Washington University. Their project at Rutgers was a study about children learning to correct their own grammar. “Dealing with this data did prepare me for college,” Olajobi says. “It was helpful getting outside my comfort zone.”

Mann hopes to add juniors to the research lab program to encourage more students to apply to college with STEM front of mind. Meanwhile, North Star is seeking other ways to help students prepare for the transition to the wider, whiter world they’ll find at college, Burnam says. A new program aims to bring North Star students together with students from suburban Verona High School to open the eyes of both sets of teenagers.

“This school teaches kids how to face the social issues that are out there,” says Steven Hightower, who is going to Brandeis University in the fall. “If we are too comfortable, we’ll never know what we’re capable of.”

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for our newsletter.