By Kim Chandler

Associated Press

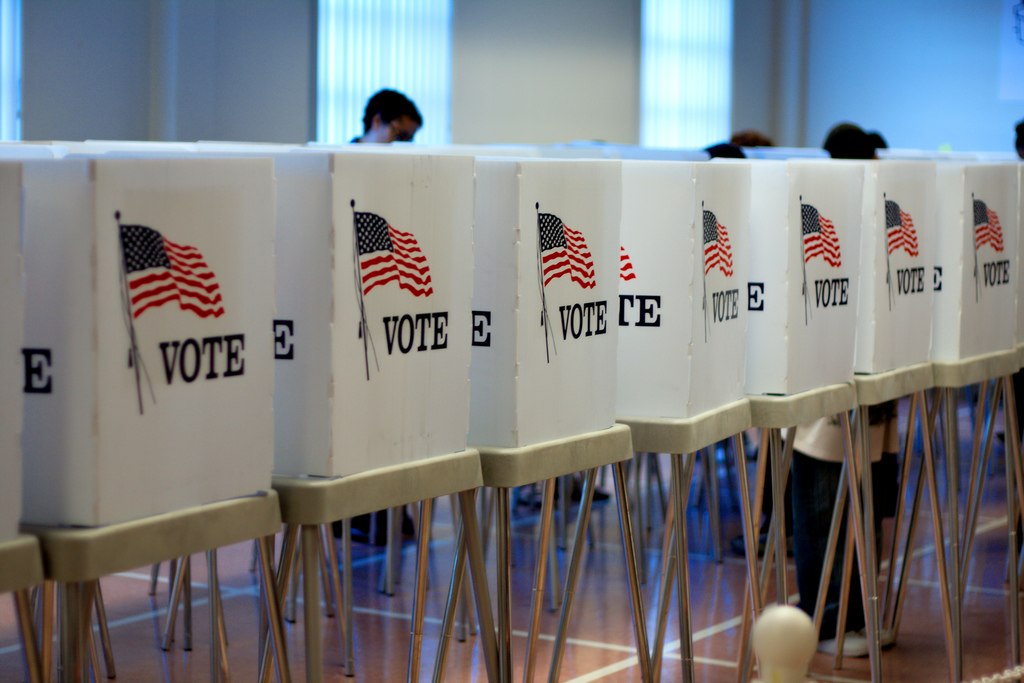

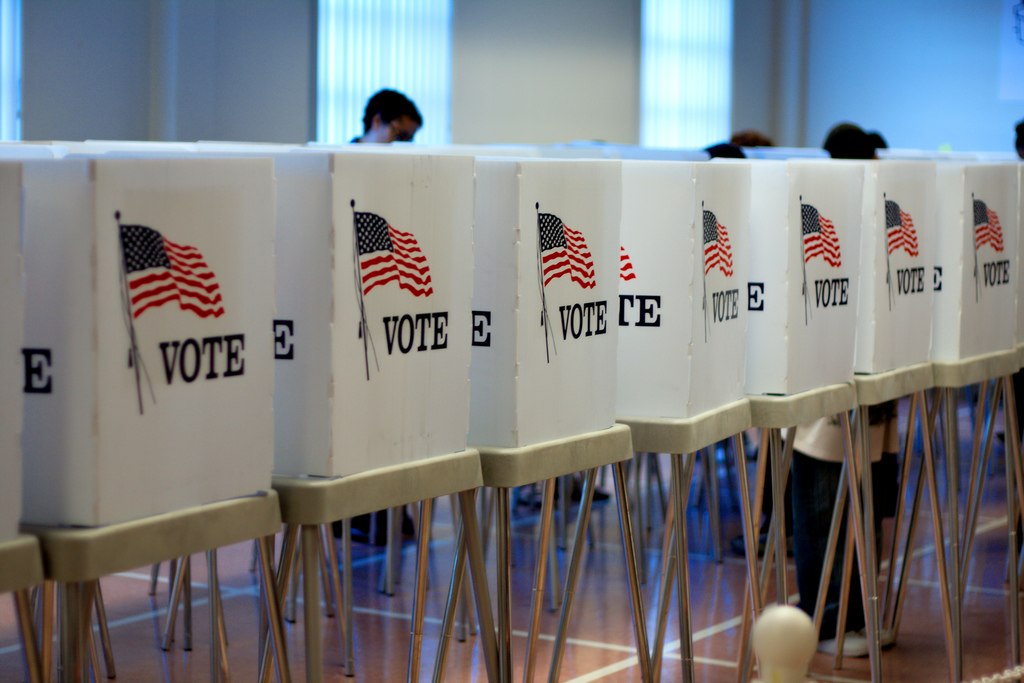

MONTGOMERY, Ala. — Alabama might allow more former felons to vote in upcoming elections after lawmakers, for the first time, approved a definitive list of what crimes will cause someone to lose their voting rights.

Alabama lawmakers last month gave final approval to legislation that defines a crime of “moral turpitude” that will cause someone to lose their voting rights. The measure, which was signed into law by Republican Gov. Kay Ivey, is aimed at ending confusion over who can, and can’t vote, because of prior convictions.

The new list of 46 types of felonies includes robbery, assault, felony theft and drug trafficking but not offenses such as drug possession.

Voting rights advocates called it a “step forward” in softening the policy of blocking ballot box access for people with criminal records – and hit African-Americans particularly hard.

“It’s like a step toward freedom after years of waiting. It’s giving people their citizenship back,” said the Rev. Kenneth Glasgow, who for years has fought to register people with prison records to vote.

The 1901 Alabama Constitution says people convicted of crimes involving “moral turpitude” are no longer able to vote, but didn’t define the term nor list any crimes meeting the definition. Politicians for decades have squabbled for decades over what crimes should be on that list.

“What moral turpitude meant in Shelby County could have been something totally different in Talladega County,” Sen. Cam Ward, R-Alabaster, said.

Danielle Lang, deputy director of voting rights at Campaign Legal Center, said there are still deeply troubling aspects to the state’s disenfranchisement law.

“Alabama still continues to be one of only a dozen states that disenfranchises people permanently even though they have fully completed their sentence,” Lang said.

People in Alabama can apply to have their voting rights restored, but must have paid their court-ordered fees and fines. “That functions as nothing more than a modern day poll tax,” Lang said.

The Sentencing Project has estimated more than 260,000 people have been blocked from voting in Alabama. Nearly half of those were African-American. The prior lack of a definitive list has sowed confusion, said Secretary of State John Merrill, who praised the passage of the bill.

Yoli Taylor of Dothan was told by local registrars in 2014 that she was ineligible to vote because of a decade-old conviction for marijuana possession, even though she had voted in 2012.

Alabama’s secretary of state at the time later contacted registrars to tell them that marijuana possession for personal use should not be considered a crime of moral turpitude under their interpretation of the law.

Glasgow wore his voter registration card around his neck when his voting rights were restored after he was released from prison.

It was proof, he said, he was a citizen again. “You really don’t have citizenship until you have your voting rights.”

Glasgow said the next step after the law’s passage is education to make sure people know they can vote.

“I am going across this state and make sure each and every person who has felony— that is not on the list — that they are registered to vote,” Glasgow said.