By Solomon Crenshaw Jr.

For the Birmingham Times

The pieces just didn’t fit for Tami Tyler. The Homewood resident’s youngest son Tyson, now 6, had been diagnosed with autism but didn’t show signs of someone who was autistic based on what she knew. In her mind, people with autism didn’t speak. Instead, they moaned and rocked back and forth.

“That’s just what I thought autism was. I didn’t know that there’s a spectrum, and all people with autism are different,” she said. “Some talk. Some are nonverbal. Some have sensitivities to certain things.”

Now Tyler knows.

Just as there is a range of colors in a rainbow, there is a range of autism—a spectrum of severity that can create issues that last a lifetime.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a general term used to communicate an individual’s challenges. People who function on the autism spectrum share similar features, but their skills and deficits may vary widely. Some children with autism reach adulthood or their teens and function well, almost to the point where they are indistinguishable from their peers.

“For the vast number of kids on the autism spectrum, there are going to be lingering challenges throughout their development that they will have to accommodate or find accommodations for,” said Bama Hager, Program Director for the Autism Society of Alabama Policy and Program, who is the mother of a 17-year-old autistic son. “They might do great, but they still need a little support in their day-to-day adult life or day-to-day work life.”

Incidences of autism have increased at almost an alarming rate, Hager said. About 15 years ago, autism affected about one in 10,000 children in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta now estimates that autism affects one in 68 children.

That dramatic increase has placed some stress on the community of professionals providing therapy, as well as schools.

“There are a lot of children who need special education services now because of autism,” Hager said. “And that number is much higher than it was even two decades ago.”

Autism and African-Americans

African-Americans dealing with autism face unique challenges.

Justin Schwartz, MD, who treats autistic children in clinics at Children’s of Alabama, said studies show that nonwhites, including African-Americans and Hispanics, are slightly less likely to be diagnosed as autistic than whites. Nonwhites also tend to be diagnosed later, he said, and that sets back treatment and potential developmental gains.

The website AutismInBlack.com cites a study titled “Autism and the African-American Community,” which notes other disparities between black and white children with autism, including access to health care, the quality of education services, and a culture of acceptance of developmental delay.

“African-American children are diagnosed three to five years later than Caucasian children,” said Arlicia Sims, mother of an autistic son, Jory, 9.

She added that many African-American households, especially those in the inner city, are “out of the loop” when it comes to autism information. Sims founded and is executive director of Jory’s Journey, a nonprofit committed to educating, empowering, and inspiring families with autistic children.

Missed Signs

Many African-Americans miss signs of autism, said Sims.

“We seem to think that’s just how the child is or that he or she will grow out of it,” she said. “As long as they’re not bothering anyone, it’s OK.”

Jory Sims was diagnosed when he was 3 years old. Before his diagnosis, Sims recalls a family member explaining his limited speech with, “Maybe he doesn’t have anything to say.”

“I knew there was more to it than that,” Sims said.

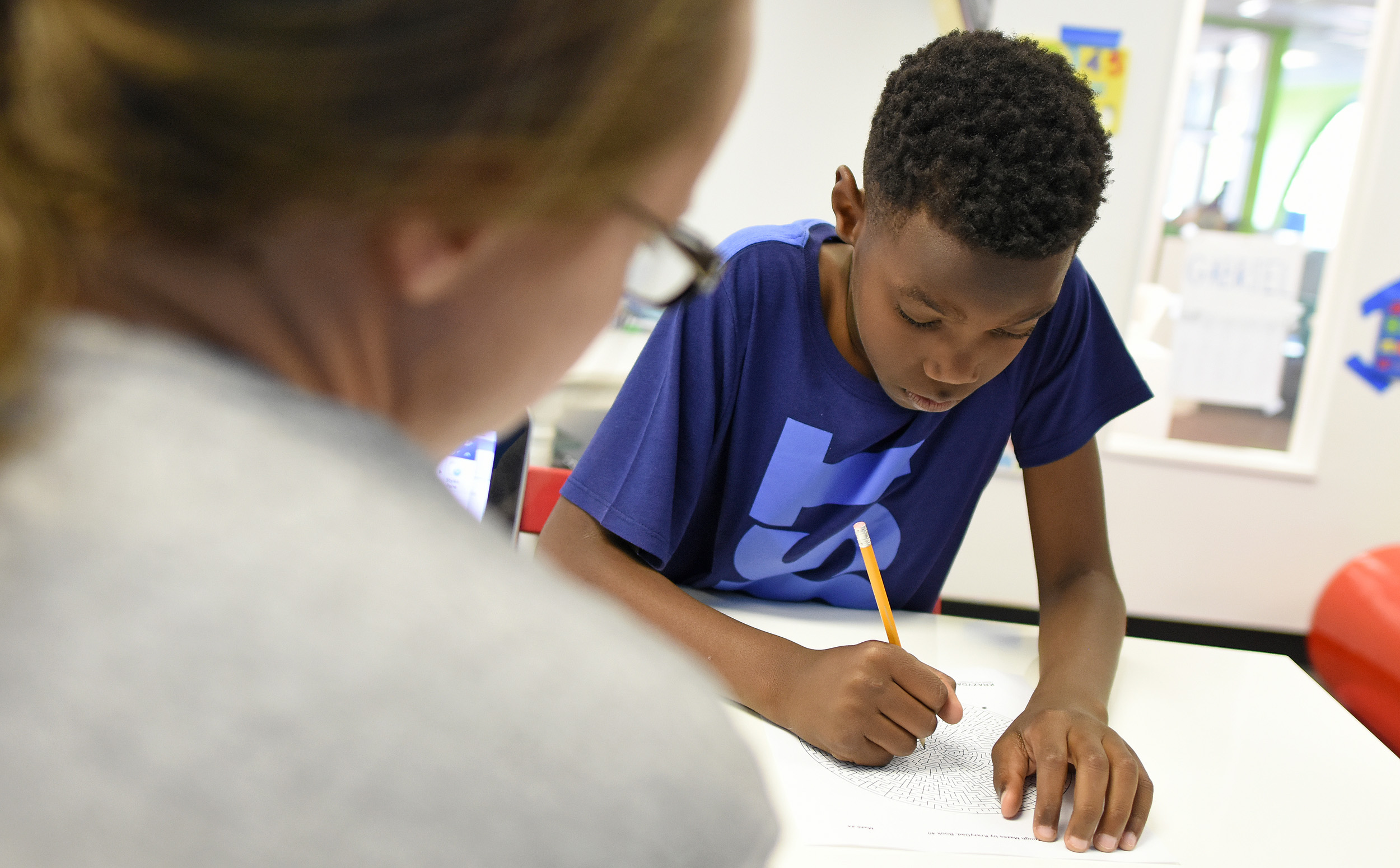

Twice a week, Jory attends therapy sessions at Puzzle Piece, a private clinic in Cahaba Heights.

René Plata, director of therapy at, and an owner of, Puzzle Piece, said the primary difference between ethnic backgrounds as it relates to autism is economic.

“The difference would be income status because of the cost of services, the type of insurance they would have, and the school system they would be in,” said Plata, who is the parent of a young adult on the autism spectrum.

Private clinics like Puzzle Piece don’t accept Medicaid, which yields higher out-of-pocket costs for households without private insurance.

“Medicaid certainly tries to cover what it can,” Schwartz said, noting areas such as occupational therapy and speech therapy. “What isn’t covered currently is intensive behavioral intervention, for which a legislative battle is being fought even as we speak.”

Alabama lawmakers are considering HB 284, the Autism Therapies Insurance Coverage Bill, which would require state-regulated health insurance plans, including state employee and teachers’ plans, to cover medically necessary treatment for autism.

On Wednesday, a Senate Committee approved HB284. It now goes to the full Senate.

Currently, 45 states have laws that require insurance companies to provide coverage for autism therapies, including an intensive treatment that teaches communication and social skills.

Schwartz, a specialist in developmental-behavioral pediatrics, said those with autism face challenges that make it appear that they have behavior problems and do not interact well socially. Still, he said, people with autism can participate in society just as equally as those who are not on the autism spectrum.

“They want people to know they have unique skills and strengths and value unto themselves. They are worth being part of society just like anyone else,” Schwartz said.

Criteria for being on the autism spectrum includes some degree of social communicative impairment that’s not explained by other reasons and some degree of restrictive repetitive and behaviors.

“Sometimes they like to do things in a particular routine … and they may have trouble deviating from that routine,” Schwartz said. “We call it an ‘insistence on sameness.’”

Ability to Excel

Brothers Victor and Christian Jackson, both students at Birmingham’s Jackson-Olin High School, are great examples of people on the autism spectrum who have found their place.

Victor, a senior, plays the cymbals and snare drum in the school band. And Christian, a junior, plays the trumpet. Each was diagnosed with autism before his second birthday: Victor at 15 months, and Christian at 18 months.

“We thought Christian was fine,” their mother Victoria Jackson recalled. “Then he started presenting signs that something was awry.”

Those signs included banging his head on furniture and screaming.

“He didn’t know how to communicate,” said Jackson, who is an aide in the Special Education Department at Jackson-Olin.

Jackson said the school is an unexpected bright light: “They have teachers who want [autistic students] to be independent. They want them to try their best, and they accept nothing less. They give them a chance.”

Band has become the community for the Jackson brothers, their special circle. They are usually the first ones in the band room for practice, always on time.

“Once you play the instrument, you fall in sync with everyone else,” Victoria Jackson said. “Being in [marching] formation, you all come together. That’s how they seem to fit in.”

‘Extraordinary’

Tami Tyler remembers Ethan Tyson Tyler, called Tyson by many, developing like his older brother. He was saying “Momma” and “Daddy,” and calling his brother “Bubba.” That changed when he turned 18 months.

“He just stopped talking,” she recalled. “Tyson had numerous ear infections. He’s had two sets of tubes. I thought he was losing hearing based on all the ear infections he had had.”

Tami’s cousin, a pediatrician, recognized signs—not talking, a lack of eye contact, not playing with other children, not responding when spoken to—and suggested that Tyson could be autistic. Conversely, his primary care physician said he didn’t see it.

“He looked at my child after only being there five minutes and said, ‘He doesn’t look autistic to me,’” Tyler recalled. “That was offensive to me.”

Asked to define autism, Tami Tyler tends to describe her son.

“The spectrum is so wide that everyone’s experience may be different,” she said. “I’m constantly trying to get people to accept that he is just like any other child, except he’s different.

“I’m always celebrating him,” Tyler continued. “I want him to grow up to understand that he’s different, but it’s OK to be different. I want him to trust that his being different makes him special—not special as in special needs, but special as in extraordinary.”